The Transfiguration

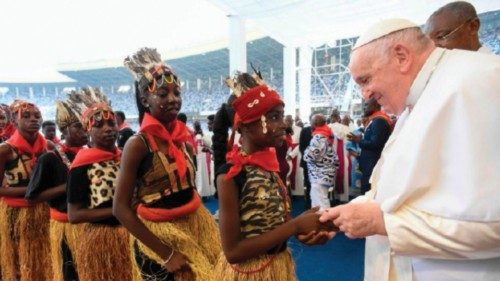

Reflecting on his successful apostolic visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and South Sudan, Pope Francis said during his General Audience on February 8, that it was like a dream come true. It was obvious from the joy that was so visible on the face of Pope Francis during this trip that he was moved tremendously by making this trip despite all odds. The NY Times captured the mutual joy that both Pope Francis and his Catholic faithful felt at his visit with the title, «In Congo, a Pope and a Nation Revitalize each other». A Congolese teacher, Tito Mwanda, captured this shared joy in a NY Times interview in these words, «To see so many Catholics in a big country on an enormous African continent counts a lot. Despite his health, it gives him a boost, it gives him more force to finish the journey of his mission». I argue in this essay that this 40th Apostolic visit of Pope Francis, his fifth to the African continent, was both a dream come true for Pope Francis as well as a moment of transfiguration for both the pope and the people.

Many Christians know the story of the Transfiguration. On the Holy Mountain, Jesus received an assurance from God that he was on the right path on the mission that he was undertaking. God also confirmed to God’s Son that he will suffer but that in the end he would be victorious. For Pope Francis, this visit to these two African countries at this critical time was like going up to the mountain. Pope Francis came on a pilgrimage of peace. He brought an empowering and prophetic message of peace and reconciliation to these two countries. His message was particularly addressed to the poor and people scared by the unbroken cycle of wars, dictatorship, ecological and natural disasters that have held these two countries in perpetual bondage. Pope Francis gave voice to many people who feel forgotten and abandoned in the lower social rungs of social and economic progress. He stepped into the shoes of our siblings who inhabit the existential peripheries in the often-forgotten brutal wars in the Congo, the Great Lakes, and South Sudan. Most people in this region for the last four generations have not known any peace or prosperity, but wars, displacement, suffering and misery.

There were many signs of transfiguration that Pope Francis and his hosts experienced. The question is whether this experience will bring about the transformation of the DRC and South Sudan and of the Catholic Church during this synodal process? Will it simply be a magical moment that fizzles out after few weeks with a return to more violence and chaos in these two countries? Only time will tell, but there are some signs of transfiguration during this trip that we can reflect on.

First, this trip was an opportunity for the Pope to take a breather from Roman politics and recent attacks to be with God’s people at the existential peripheries. Pope Francis alluded to these attacks in both his interviews to the Associated Press and on his flight back to Rome from South Sudan. The days and weeks leading up to this visit brought out all the fault lines in today’s church. One would have expected a greater focus on Africa and her peoples, and conversation on how this continent that is now the fastest growing Catholic continent in the world could be supported to achieve its destiny. Rather, what emerged were commentaries on Pope Francis’s undue attention to Africa and the margins against the European mainland. Some others have questioned the reform agenda of Pope Francis, especially in opening the Church to an internal conversation through the ongoing synodal process. For the neutrals, this was quite a new level of escalation at a time when the Holy Spirit is inviting the church to a deeper humility and heightened attention to the God who reveals to us new truths in moments of silence and adoration.

It must be admitted, however, that the Catholic Church today is deeply polarized. It is not the creation of any single Pope, but it is also the sign of an institution that is growing beyond a single narrative of identity and communion as this great tradition crosses different cultural and spiritual frontiers beyond the West. It is also a reflection of the drama of our times and the complexity of history. This is because humans as they grow in faith in God search sometimes in the dark for how to bring the complex and changing human realities and the ambiguities of time and temporality to conform to the will of God. This search is not simple or clear cut because the aptness of divine revelation to any point in history is often not discerned in a single and immediate firm grasp of the ineffable ways of God.

Whatever be the case, the polarization in the church which often has mirrored the polarization in the wider society has created theological fissures which are deep, and seemingly unbridgeable. Underneath the Church today are many rumbling contestations on questions of pastoral ministry, sexual identity, mission, faith, morality, pastoral life, and the role of theology and the Church in society. These rumblings have weakened the ability of many local churches to develop creative pastoral accompaniment or skills for a robust engagement with social change, practices of inclusion, and cultural pluralism. Contemporary Catholicism is often caught up in a schismatic divide whose lines of battle are hardening by the day sometimes over the hope or despair of a possible change in the Church’s teaching which over time can never be realized by a change in the revealed truth that the Church is called to offer to the world. The synodal process that is underway offers the opportunity to penetrate these contentious issues with courage, candor, clarity, and respect for contrary perspectives without division and personal attacks. These contentious issues were all swirling around the Vatican on the eve of the Pope’s departure to Africa. Pope Francis has refused to be distracted by these criticisms. Rather, he has welcomed them with an open spirit as part of the synodal process. He has been steadfast in his commitment to the missionary reform that he programmatically proclaimed in Evangelii Gaudium.

Viewed in this light, Africa offered Pope Francis a depolarizing space for a deeper encounter with the people whose voices he has mediated throughout his papacy. Here, Pope Francis came face to face with the testimonies of people who have found hope through their faith whose sensus fidei fidelium the Pope invites the Church and all Christians to embrace in these words «Each of us can learn something from others. No one is useless and no one is expendable. This also means finding ways to include those on the peripheries of life. For they have another way of looking at things; they see aspects of reality that are invisible to the centers of power where weighty decisions are made» (Fratelli tutti, 215). The sensus fidei was embraced by Pope Francis when he met with women, youth, victims of war, children who have found life amidst the unbroken chain of pain and suffering built on the architecture of violence that is baked into the checkered history of these two countries. In encountering these giant witnesses of faith, the Pope, saw «the force that can transform the country» and «the seeds» for building a new, unified, reconciled, and peaceful country. Through the mutual exchange in this encounter, Pope Francis invites us all to see how God is revealing to the world the rationality of faith and validation of God’s existence through the courage, resilience, hope, and solidarity of the people at the frontiers of whom Pope Francis speaks about with so much passion and pain.

Furthermore, the visit to the DRC and South Sudan offered Pope Francis the opportunity, like the Good Lord on the Mount of Transfiguration, to be transformed through the culture of encounter with the people whose lives, faith, and present context and future hope rest on the success of the reforms that he is pursuing. The culture of encounter is central to the praxis of missionary conversion. Pope Francis often uses phrases like «gaze upon», «openness of heart», «spiritual encounter», «the art of listening», «contemplation with wonder,» and the «gaze of Christ» in inviting people to this culture of encounter, so that they can appreciate the different forms of beauty in their lives, in the lives of others, and in the world of nature. The culture of encounter opens a sense of mystery which moves people to appreciate beauty even in the suffering and tragedies of life. Through encounter with nature and our fellow human beings from every part of the world, one can grasp a deeper level of truth in the sublimity of being and the beauty of all things.

Sadly, the modern world often objectifies the other, rather than seeking out encounter. This is what Pope Francis noted when he speaks of the exploitation of Africa and why the rest of the world should ‘hands off’ Africa. Pope Francis bemoans modern society’s objectification of others as evil because it «seeks to domesticate the mystery» of God, nature, and people (Gaudete et Exsultate, 40). In this kind of culture, there is a loss of beauty and an instrumentalization of the other; people are no longer encountering the other as a gift, but everything is seen through a transactional exchange of products, commodities, and profitability, as if humanity is simply a collection of faceless consumers in systems of profit, power, and domination. Isn’t this what the Pope saw in these two countries and the destructive effects of the economies that kill, exploitation, dictatorship, corruption, failure to forgive, and the denial of agency to the poor through the lack of freedom caused by poverty?

As he sat on the raised altar in Kinshasa’s airport for the open-air Mass and seeing the vast sea of millions of people who gathered for the Mass, Pope must have felt deep within himself that the liberation of these people from the clutches of poverty, exploitation, and suffering, will require a church that is poor like them; a church that looks like them, truly African and truly Catholic and a prophetic church that makes common cause with the poor so that God’s reign may come in their lives for their flourishing, human fulfillment, and integral salvation. And if such a church must emerge in today’s context, then placing the poor and their liberation at the heart of the Church’s systems, institutions, structures, and pastoral life becomes a necessary first step for missionary conversion.

Finally, the Transfiguration was for Jesus a confirmation of his mission. On that holy mountain, Jesus got a bird’s eye long shot view of the suffering of the passion that he was to undergo. Pope Francis is going through a time of passion both in his physical suffering because of his painful knee, and the tension, contestations, and polarization that are emerging in the synodal process all of which must move him to an inner conversation on the direction of the church. While the papacy is not a popularity contest, many people in both the Congo and South Sudan travelled hundreds of miles to catch a glimpse of the Pope. They came in their numbers because they love God and see in the Pope a sign of God’s presence among God’s people. These large crowds of faithful who believe in his leadership that lined up the streets to meet him in Kinshasa and Juba, and the millions that gathered for the masses must have given the Pope a big boost like the heavenly visitors to Jesus on the Mount of Transfiguration.

Hopefully, this experience must have offered Pope Francis an inner confirmation of the validity of the mission that God has given him when he was chosen to reignite the flames of reform lit at the Second Vatican Council. He must have received from these millions of people who came to see him a new strength to fulfill for the church and the world at this point in history the dream of Vatican ii. The visit was so well planned to give voice to victims of wars, natural disasters, and sexual violence and abuse in the church, grassroots organizers and change agents, pastoral agents and church leaders who serve the most vulnerable of society. In encountering the voices of these giant witnesses, Pope Francis received afresh from their stories a clear message like the one given to him after his election as Pope by the late Cardinal Hummes: «don’t forget the poor».

But the transfiguration of Pope Francis was not simply his own subjective experience; it was also a summons to our shared ecclesial experience of communion, mission, solidarity, and participation. Pope Francis has invited the world to take another look at Africa and all that she represents. Travelling to Africa has always been for many non-Africans a surprising experience for many reasons. Pope Francis expressed this pleasant surprise and joy both on his return Flight to Rome in 2015 from Banjul, and on his return to Rome from Juba in 2023. Visiting Africa was for Pope Francis a moment of gift exchange. Most people who visit Africa with an unbiased mind like the Pope and many other popes before him experience a transformation of perspectives about Africa, the world, human flourishing, and about themselves. This transformation is always the result of a deep culture of encounter. The world needs to see Africa as a land of hope and assets that requires solidarity, not sympathy. Africa is also a land of deep faith where Christianity has taken roots and have borne tremendous fruits. This rich land is the soul of the world today or as Pope Benedict xvi noted, «the spiritual lungs of the world». However, this African Mother with her strong and faith-filled sons and daughters continues to celebrate the gift of life amidst the constant internal and external factors that zap the energy and resources of the land and her people.

Through Pope Francis’s visit, the Church has turned her gaze on Africa; but will it be a permanent gaze or simply a temporary distraction that will soon fizzle out? The Christian expansion and the strong following that Pope Francis experienced in Africa is not simply the result of a people’s response to God through a pathological faith that verges on superstition and escape from suffering. Rather, it is an experience that is at once natural to their understanding of reality and history, and borne out of an experience of the saving, healing, and liberating encounter with the Son of God. Christianity is expanding in Africa not because Africans are superstitious or are poor, but rather because Africans are religious. Africans are not becoming more Catholic because they are poor; they are becoming more Catholic because they are religious. In addition, Catholicism captures the religio-cultural imagination. This is because Africans find in the Christian religion and in the Triune God, a fulfilment of their deepest desires buried at the heart of these cultures and her deep religious and spiritual moorings. Catholicism has the capacity of transforming Africa through a new level of growth not simply in number but in spiritual and moral influence. This transformation if sustained is capable of birthing Catholic intellectual, social, and spiritual traditions for the realization in small ways of the fruits of the eschatological reign of God in Arica and beyond.

The hope is that this visit will reinvigorate Pope Francis in his reform agenda. This transfiguration experience should also offer him some added motivation and impetus to continue to pull down the idols of power, privilege, self-absorption, and self-proclamation that sometimes take away the focus of the Church from the priorities and practices of the poor man of Galilee. These tendencies often numb the church’s perceptive capacity to see the signs of the times or correctly interpret and respond to them in proclaiming and enacting the Gospel message of Jesus Christ.

On the other hand, African Catholics should respond to Pope Francis’s incessant call to them to find solutions to their own problems by building on this momentum particularly in the continental synodal conversation. African Catholics should deeply reflect on the hopes and despairs of our people, the so-called African predicament that has endured for years, and the promise that lies ahead of the continent in this moment of Africa. The African continental synthesis must harvest the voices of those at the existential peripheries and bring to the synodal table Africa’s own unique agenda for reform and renewal of the Church in Africa so that African Catholicism can realize the huge potentials of the exponential Christian expansion in the continent.

African Catholics and peoples need to see concrete signs of the transformative power of the Gospel that can bring Africa to the day of salvation and wipe away the sad memories and histories of the former times. This is because it really comes to nothing if you tell a hungry child that God loves them without giving them food; or if you preach the mercy of God to a sick woman without offering her an affordable and reliable healthcare system or to assure people of a better future through exuberant liturgies without showing them how a praxis of social transformation can turn their hope into reality through the agency of their faith and life. The kingdom of God does not simply begin and end with proclamation and claims or with papal visits. However, a transformative papal visit like Pope Francis’s offers the people of God the footprints of God that they can follow to witness a glimpse of what is possible and what is to come — just like Jesus and the three disciples saw the future victory after the Paschal Mystery on the Mount of Transfiguration. The realization of this hope is so important for all of Africa and the world but more so for the DRC and South Sudan, two African countries that have borne the weight of suffering and the ravages of history for far too long.

di Stan Chu Ilo

Priest of Awgu Diocese, Nigeria Coordinating Servant of the Pan-African Catholic Theology and Pastoral Network (Pactpan)