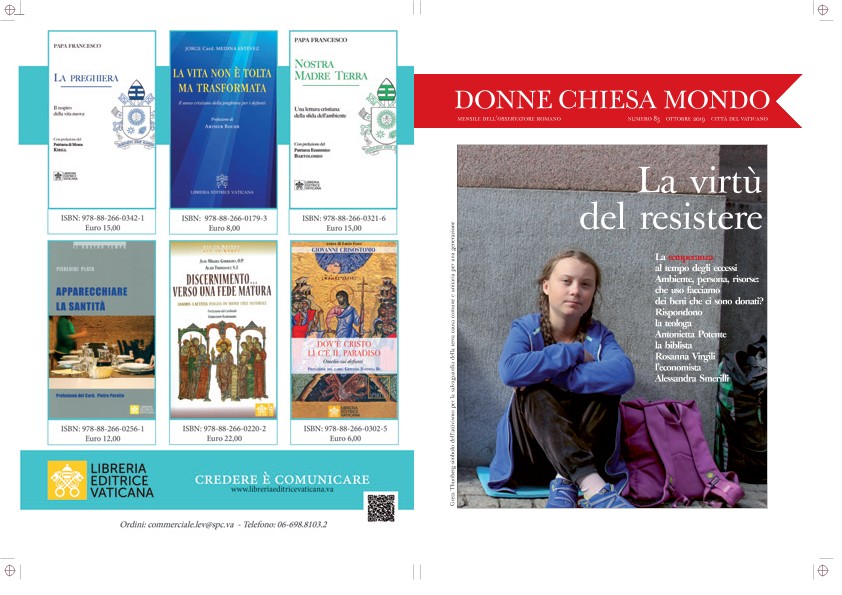

La virtù del resistere

The ancient philosophers urged people to act with temperance, understood as the mid-point between two excesses: intemperance on the one side and insensitivity on the other. The Delphic Oracle’s μηδέν άγαν (nothing to excess) and Horace’s principle of the aurea mediocritas (golden mean) come into the Christian definition of the cardinal virtue of temperance, very often portrayed by the image of a woman mixing hot and cold water.

Further, temperance designates the capacity for satisfying one’s instincts and desires with moderation and is associated with balance and self-control. But it is neglected or disputed today more than it used to be in the past. This is because the lifestyles proposed to us, or indirectly imposed on us, are themselves all too often lacking in balance and moderation. Thus it happens that we are encouraged into excesses – even strongly attracted by them – and into considering temperance as an outmoded garment. What, however, are the consequences of this lack of self-control, this lack of respect for measure in the use of our possessions, our bodies and our planet? Dependences, abuse, crime and sexual perversions, ecological damage, administrative and political corruption, arrogance and haughtiness, small or larger acts of revenge are apparent to all. The call to seek and to exercise temperance and sobriety is thus still as valid today as it was in the past. But it is also useful to remember that temperance, like the other virtues, is perfected at the moment when one enters into a profound spiritual dynamic. If, in fact, to temper means to prepare something well for one’s use – yes, just as we sharpen a pencil in order to be able to use it properly – it inevitably follows that we question ourselves on the ultimate end of existence. In this way it has been granted to us to discover that this ultimate end is not the achievement of the happy medium, nor is the ascetic crucifixion of the flesh or conformity to preconstituted rules an end in itself. Rather it is the joyful response of everyone to a call, to having Love as the centre, as the only firm point, and not just the happy medium. Hence the invitation to let the “right measure” (metron) itself to be “tempered” by Love and transformed into a harmonious, luminous dance where nothing rigid, cold, defensive, calculated or unilateral any longer exists. Who knows whether a great poet understood this very thing when he wrote: “Except for the point, the still point, / There would be no dance, and there is only the dance” (T.S. Eliot).

Francesca Bugliani Knox

PDF

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti