byPiero Loredan*

Over the past twenty years, numerous films have offered a glimpse into the condition of women in the Middle East. These movies have sought to highlight their longing for freedom and emancipation within the context of Islamic culture and religion. Among them, Wadjda, Persepolis, and The Breadwinner offer various points for reflection.

Wadjda [The green bicycle]

The 2012 film by Haifaa Al-Mansour is revolutionary in itself. Afterall it was the first feature film entirely shot in Saudi Arabia and the first film in the Country’s history directed by a woman.

The heroine of the film is Wadjda, a lively and rebellious young girl. She lives in the outskirts of Riyadh, between a mother who submits with painful resignation to local traditions and a father who is ready to take a second wife.

Wadjda is a rock music fan, wears jeans and sneakers unlike other girls her age, and dreams of buying a green bicycle. It’s a bold challenge, after all, for a Saudi woman, riding a bike is provocative, even considered blasphemous, but she does not have enough money. Determined as she is, the young protagonist begins her courageous journey. First, she decides to enter a Quran recitation competition at her school, where the prize is a considerable sum of money.

The mother plays a key role in Wadjda's journey. Unlike her daughter, she seems to have never desired to break the rules. Although worried about her daughter's boldness, she also admires her defiant spirit.

The film is delicate and refined, both in its portrayal of female characters and in its depiction of male figures, who are drawn with great sensitivity. While the situation of men is certainly more privileged than that of women, their attitudes reflect a general disregard for women themselves. Still, more than aggressive despots, they appear as individuals shaped by the rules of a patriarchal society, who are victims of a deeply rooted system, and are incapable of acting otherwise. What is particularly interesting from this perspective is the character of Iqbal, the driver who takes Wadjda’s mother to work. He is rude and unsympathetic, nonetheless he benefits from a sort of “mitigating circumstance. Over the course of the film, we learn about his suffering as an immigrant worker forced to live far from his family and who hasn’t seen his daughter in years.

The religious dimension is also approached with nuance. Despite her lack of interest in religion, Wadjda signs up for the Quran recitation contest. The Quran becomes a springboard, and the verses sung by the young protagonist ring out sweet and melodious, and carry true beauty.

What is equally fascinating is the emphasis on the color green, which holds special meaning in Islamic culture. According to various traditions, green was the color of the Prophet Muhammad’s cloak and turban. Furthermore, the Quran states that the inhabitants of paradise will wear fine green silk garments. Could the green bicycle dreamed of by Wadjda symbolize a horizon of hope, for her, and for the condition of women in some Middle Eastern Countries?

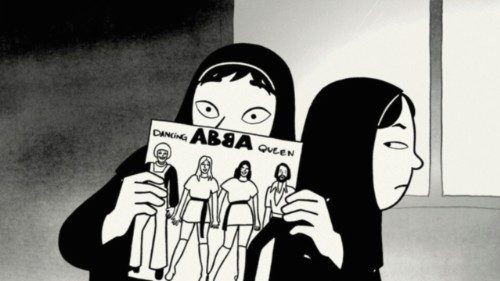

Persepolis

Winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes in 2007, the animated film Persepolis is the adaptation of the autobiographical graphic novel of the same name by Marjane Satrapi, which was published in France in four volumes between 2000 and 2004. Like the comic it is based on, the film is a moving and enlightening evocation of 1980s and 1990s Iran, seen through the eyes of a young woman. It recounts the Shah’s fall, the Iran–Iraq war, the protagonist’s arrival in Vienna, and the years of deep solitude that followed.

The visual style can be described as “stylized realism”, with drawings closely adhering to real-life experiences. However, dreamlike moments are also present, and the world of dreams interrupts the realistic graphics, and offers a poetic perspective on the scene.

In this way, compared to live-action cinema, animation lends itself more naturally to the integration of epiphanic moments, brief instances that seem to transfigure reality, blurring the boundary between everyday life and the realm of the sacred. A good example are the three brief dialogues with God, which though short are meaningful moments throughout the film. God, though rarely appearing in the story, is a comforting presence, who is attentive to educating the protagonist about the true meaning of justice and encouraging her in times of apparent hopelessness. He becomes the one to whom she can shout her rage in the face of unjust suffering.

As a whole, the film is both a personal and a political traumatic awakening to life. It is a hymn to freedom and human dignity, which is suffocated both by the political-religious fundamentalism of Tehran and the liberalism of Vienna. As with Wadjda, a female family figure plays a key role in the protagonist’s coming-of-age journey: in Persepolis, this is the grandmother, a lively elderly woman with a delightfully rebellious anti-system stance.

The Breadwinner

In the animated film The Breadwinner (2017), the heroine is a young girl from Kabul who is fighting to support her family under the Taliban regime (1996–2001).

The film was co-produced by actress Angelina Jolie; the film is based on a children’s book by Canadian author Deborah Ellis. It is the first feature film by Irish director Nora Twomey, and was nominated for an Oscar

The story follows a young girl on her journey toward adulthood. Parvana learns to make her way in a world where being a woman means submission. After her father, the only adult male in the family, is unjustly arrested, she decides to disguise herself as a boy in order to gain the freedom necessary to help her family. Over the course of the story, Parvana’s world gradually expands, from her home to her neighbourhood and then to the city. Together with her friend Shazia -who is also disguised as a boy in her pursuit of freedom, the two girls open up to the possibility of claiming the entire world. By leaving home alone, they begin to discover who they are. At the same time, Parvana’s mother finds the strength and courage to assert her unassailable dignity.

One of the gems of the film is the legendary tale of Sulayman and the Elephant King, which regularly interrupts the main narrative and mirrors the heroine’s journey. Sulayman’s struggle against the brute force and darkness of the Elephant King reflects Parvana’s battle against violence and obscurantism.

In The Breadwinner, as in Persepolis, the realistic animation style used for the sequences set in Kabul gives way to a different aesthetic. Inspired by the visual language of traditional Persian tapestry, the imagery in Sulayman’s story evokes the timeless quality of a fable and, at the same time, gives tangible form to the story’s spiritual power, which is an intangible yet essential force for facing everyday reality.

In their own way, the three films each portray the human journey of the young women protagonists who strive to affirm their incorruptible human dignity. However, none of the films resorts to simplistic binaries: there are no “Good” (women) on one side and “Evil” (men) on the other.

Moreover, with multi-layered spiritual insights, these films touch on the inner life and search for meaning that belong to every person. Finally, in no case is Islam or the God of Muhammad attacked; rather, it is religious fundamentalism that is called into question.

*A Jesuit, and theology student in Paris at the Facultés Loyola

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti