History teaches us that every revolutionary push is followed by a period of restoration.

It is therefore no surprise that, even after the feminist revolution -which began at the end of the 19th century and is still ongoing- we are witnessing unexpected steps backward. In fact, throughout its gradual unfolding, the feminist movement has required persistent resistance, given the many hesitations and, at times, outright hostility it has encountered from a patriarchal power structure deeply rooted in history, laws, customs, and even consciences. To these, political, social, religious, or even gender affiliations could be added.

The Church, for her part, has always adopted with great caution the demands that arise from the world of which she is a part, and, above all, processes them with notable slowness.

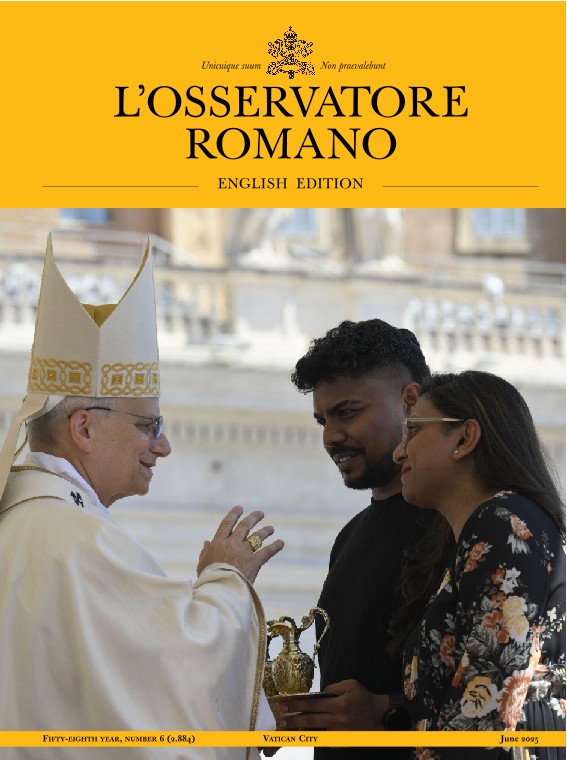

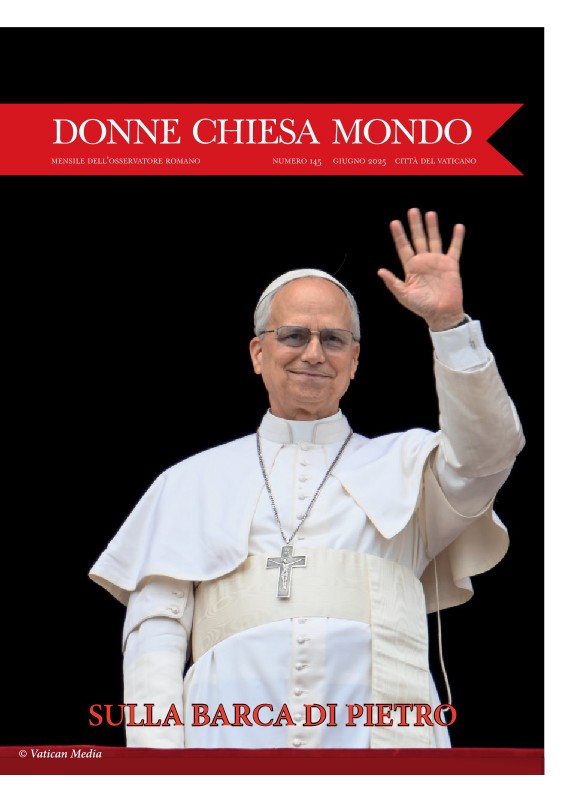

There is no doubt, however, that Pope Francis, who referred to himself as the pontiff “from the end of the earth”, despite reaffirming his distance from feminist thought, showed, with repeated determination, that even within the Church, times have definitively changed. We only need to consider, on a practical level, the appointment of many women to roles within the Vatican administration, or, on a more theoretical level, the neologism he himself coined, namely to “demasculinize” the Church. This statement had considerable communicative impact due to the immediacy with which it conveys an entire universe of meaning.

There is no going back, it is true. However, the journey of peoples, like that of individuals, is not always driven solely by forward momentum, nor does it always follow a linear path.

It is true that feminism has brought about a decisive turning point in all cultures across the globe. This has occurred more forcefully and visibly in certain countries more than in others, which has depended on the ideological and economic disparities between regions. Yet it is equally true that appearances today suggest quite the opposite, which is the witnessing of a reassertion of patriarchal power, as ever faithful to itself, and sees itself as invincible.

For the first time, we are witnessing both men and women claiming and managing power according to what might be described as a shared “patriarchal genome”. This signals a profound shift in the rules of the game, i.e. that patriarchal power has become unisex. It no longer needs to legitimize itself by systematically excluding women from positions of publicly recognition authority, nor must it disguise itself in romanticized sublimations of the feminine. Yet, although the history of women has often followed a subterranean or hidden path, the feminist revolution has taken on such depth and breadth that it is unlikely to be consigned once again to oblivion. The reasons for this are plain to see.

First, on a general level, there is no turning back from the awareness that each individual’s sexual identity is a broad and complex reality and one that is neither static, univocal, nor uniform. Nor is there any going back to a way of thinking that, having moved beyond the monopoly of binary dialectics, has embraced complexity as its mode and weaving as its method, as in the interlacing of threads. One might argue that this belongs only to the world of “the two Wests” and has little relevance for other worlds of life and thought, of customs and beliefs. That may be true, but are we really sure that Nicolaus Copernicus or Galileo Galilei, who revolutionized physical science, are the exclusive heritage of Italian culture? Or, that Ada Lovelace, the mathematician who in 1843 wrote the first algorithm intended to be executed by a machine -thus inventing software- is the sole property of British culture? Or, are they not instead part of the universal human legacy that humanity as a whole has drawn upon for its growth and development? After all, even the Taliban use smartphones!

Second, because the now-globalized awareness that gender identity and orientation have become inalienable foundational criteria for understanding the human condition is the fruit of the various feminisms that have most deeply taken root in the public discourse of all international bodies. Any attempt by men and women in positions of power to shout against this consensus may make the journey more arduous and slow it down, but it cannot reverse its direction.

There is, however, a strong sense that, while the world is visibly rehabilitating machismo thoughts and practices, the Church is instead struggling in her laborious search for new horizons in order to develop an anthropological -and thus theological- vision that is finally inclusive. In addition, to heal the wound of gender injustice that still makes her one of the most resistant patriarchal systems in the world. We shall see whether and how, after Francis, the effort to “de-masculinize” the Church will face setbacks or receive fresh momentum.

The Catholic Church is advancing slowly, but churches are the only institutions where the issue of authority and power is at stake not only in terms of redistribution across genders and throughout the ideological, political, and social spectrum, but also in terms of thinking about God. The theologian Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza called this system kyriarchy, which is the domination of any group over another, and insists that what is at stake today is not merely the democratic sharing of power envisioned by feminism, but that Christian theology aims to revise the very nature of power itself, even that of God, the Kyrios.

To explore new faces in positons of power and new ways of managing the various forms of authority is the task that the feminist revolution has entrusted to future generations. This is the new challenge posed by intersectional feminism, which neither isolates nor absolutizes gender justice, but places it alongside struggles against racism, militarism, poverty, and environmental degradation. This is what lay at the heart of liberal democracies. It is a task that all Christian churches cannot but embrace; after all, at the very core of their DNA lies the song of a young woman who believed that her God “has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts, he has put down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted those of low degree; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent empty away”. (Luke 1:51–53).

By Marinella Perroni

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti