Sister Véronique Margron is a moral theologian, and president of Conference of Religious Men and Women of France (CORREF). In addition, she has been the Provincial Prioress of the Dominican Sisters of the Presentation since 2014. Sister Margron believes that the main challenge to the “de-masculinization” of the Church, as envisioned by Pope Francis, is the development of a culture of otherness.

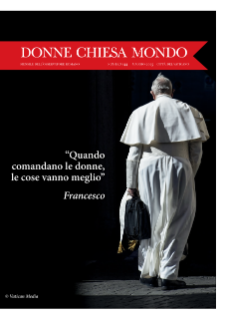

Pope Francis launched an appeal in 2023 to “de-masculinize” the Church. Do you think this is happening?

My observations primarily concern the Church in France, as this is where I live and hold positions of responsibility, although I am obviously in contact with sisters around the world. As for the Church in France, we are facing a mixed, evolving, and contrasting situation. For some time now, some women have held significant positions of responsibility in the dioceses, either as diocesan economists, heads of catechesis, or as members of episcopal councils, at least for the past fifteen years, although this is not the case everywhere. In about ten or so dioceses in France, there are delegates -or general secretaries-, with authority and considerable power. There are also women entrusted with safeguarding minors. Therefore, it is true that a path is being initiated, but it is too early to speak of de-masculinization. The situation is far from catastrophic, but there is still a long way to go before the responsibilities held by women become the norm.

What does “de-masculinizing” mean to you? “Feminizing”?

In my opinion, it is primarily about recognizing that otherness is not only normal but also essential, and that we benefit from integrating it into governance. Otherwise, we remain behind closed doors, in a form of self-isolation that is potentially dangerous and sterile. Otherness is a spiritual and moral obligation. It is a vital and bodily necessity. Moreover, this reflects the concrete reality, since Sunday assemblies are made up of both men and women, and the female presence, moreover, makes up the majority. Nevertheless, it also concerns otherness between priests and laity, between men and women, sociological otherness, and even intellectual otherness, although for those in positions of responsibility, it is always difficult to surround oneself with close collaborators who think very differently. However, this horizon of multi-level otherness should never be lost sight of, as the fundamental challenge is for the Church -and her governance- to increasingly resemble the People of God in all its diversity.

In practical terms, how can we proceed with the issue of the glass ceiling? What responsibilities should be opened up to the laity in general and women in particular?

At the diocesan level, for example, I think it is desirable to generalize or multiply the roles of general delegates and general secretaries. Then it is essential that these individuals be able to remain in position long-term, and for this reason, they should be appointed. It will take time. Even appointments to episcopal councils allow progress in this direction, as long as these councils have real power, because it is not about appointing a woman here and there to show that minorities are respected, especially since women are not a minority. I fully understand that there are matters that should only be handled by the bishops, but perhaps on a number of issues, there remains a wide margin for improvement in the allocation of responsibilities. This happens at different levels simultaneously; for example, parishes, local life, which corresponds to the real, everyday life of the Church, but also more symbolic instances.

But, how?

We must be wary of models to imitate and simplistic answers. In this area, I do not think anyone can claim to be a model. However, as a Dominican religious, I observe that, regarding women, religious life has a long experience with the model of governance, dating back to the very beginnings of religious life itself. I would not elevate it as a model because I am also aware of its limits and pitfalls, which can be as strong as those of men. Nevertheless, it seems to me that this type of governance in religious life is interesting. It is more modest because it is generally more temporary, as it is rare to remain in positions of leadership for life, and where councils are mandatory. This does not mean that everything can be copied by dioceses, as that would not make sense since they are different institutions, but there are undoubtedly methods to be inspired by.

Is there not a risk associated with this reflection to essentialize qualities that are intrinsically feminine or masculine?

Of course, it does not mean that a female governance would be inherently less authoritarian, or that with women in power all problems would be solved. That is not true, in society, in politics, or in the Church. It is often said that women tend to be more concrete, but that is not always true. Fortunately, I know many men who have a very concrete relationship with reality. Therefore, it is risky to try to extrapolate traits that would be inherently feminine or masculine. Nevertheless, I think we will have made progress when women are appointed who do not have to prove their legitimacy to hold a position twice as much as men. We are all immersed in our cultures, which are steeped in influences that shape our way of being in the world, of being men or women. In this sense, education is key to normalizing the fact that in society and in the Church, both men and women are capable of taking part in decision-making, and both gain from working together. It is therefore a good thing that there are women teaching in seminaries, as is already happening, and that they are genuinely involved in decision-making processes.

You mention the example of religious life. However, what is the relationship between authority and general superiors?

Obviously, there are historical contexts of abuse of power, structurally abusive from their very origins, which only a higher ecclesiastical authority can or could put an end to. Then there are contexts where the abuse arises in a more subtle or insidious way, because a religious finds herself in a position of authority before a small group of very elderly sisters, on terrain marked by a very strong culture of obedience and a lack of formation. However, the vast majority of general superiors I meet are women of great courage because they face difficult issues related, for example, to the aging of their sisters, as well as tough situations of war, with painful cases of conscience. For this vast majority, governance is unthinkable without coordination, without dialogue, without questioning. Sometimes the problem is even the opposite, namely that they have difficulty exercising their authority for fear of abusing it.

by Marie-Lucile Kubacki

The person in charge of the religion column of “La Vie”, a weekly French Roman Catholic magazine

#sistersproject

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti