“It is hard living here in the camp. I was doing well in Sudan, where I lived with my husband, mother and children; but the war forced us to flee. During the escape, we became scattered; some of our family were killed, among them my husband and my mother. One of my children was taken; I no longer know where he is”.

Mariam is in her early twenties. Physically emaciated and without strength. She is breastfeeding a baby girl, her third child called Salwa, who was conceived while fleeing Sudan and born in the Malakal refugee camp in Upper Nile State. “I try to earn a living by bringing water to drink and water to cook with from the pump to the tents. For this small service I get paid a few pounds (Sudanese currency ed.) but it is never enough”.

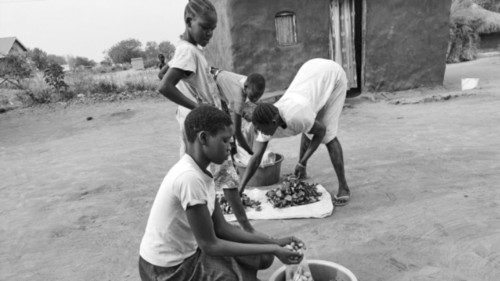

Rice, maize, beans. We eat what there is in Malakal, South Sudan. Hunger is among the first consequences of war, sometimes killing more than weapons. Moreover, women are the first to find food and often the last to eat it.

Sometimes fresh fish also arrives at the camp, which is caught in the river and those who can afford it buy it at the market. For the rest, the food is provided by the World Food Programme, which delivers it every fortnight to Caritas, which redistributes it among the refugees. The early displaced persons cultivate small patches of land and sell the fresh vegetables. “I can say that I have saved my life”, Mariam repeats, thanking God for this, “but I no longer have my family and I don’t work”.

The civil war has torn Sudan apart. The Country lies on the other side of the border, and has produced a record seven million internally displaced persons and refugees. Until 2013, Malakal was a thriving port city on the White Nile; today it is an endless expanse of tents and shacks; pots and fires, rags and hunger. It is home to 50,000 people, most of them from Sudan. The Rapid Support Forces and the Sudan National Army cannot agree on a cease-fire. Therefore, the country has emptied out.

With hollowed cheeks and downcast eyes, Mariam recalls that the “problems started in Sudan almost two years ago and so we left. On the way from Khartoum to Renk, across the border with South Sudan, I found myself separated from my brothers and relatives. We met some rebel soldiers, those of the RSF, who attacked us and so we dispersed”. Mariam caresses her daughter, hoping to one-day return home, to Khartoum. To do what she used to do. To try to live her simple life. Which before the war was not rich but not so desperately miserable either. (Ilaria De Bonis)

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti