It is a rare link between women artists and the “masculine” theme of war. This has always been the creative monopoly of men who have constructed metaphors with figurative language but also with informal painting, which exploded in the mid-20th century as an expressionist reaction to the Second World War. Although the reasons for this rarity are manifold, the first reason concerns the male factor in the theoretical and practical issues of war. There are exceptions that stand out due to the anomaly of a maternal gaze on the unspeakable; exceptions that we see in modern times, particularly with the advent of photography, the tool that democratized the link between female artists and civil society, the medium that offered women the opportunity to be militant witnesses of major historical events.

In the wake of the exceptions that confirm the rules, let us recall two artists who favoured manual skills as a human reaction and a moral lesson around war.

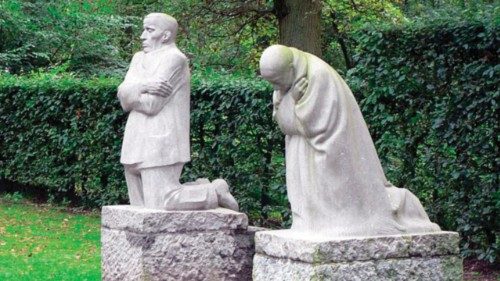

Käthe Schmidt Kollwitz (1867-1945) was a German expressionist who used painting, sculpture and graphics on paper. The loss of a son in 1914 led her, during the grieving process, to design a sculptural memorial entitled The Grieving Parents, which is now kept in the Polish cemetery in Vladslo. This is a complicated work, an initial draft of which she destroyed in 1919, then resumed in 1925 and finished in 1932. It is the sculpture where a couple condenses their excruciating grief into a posture of eternal waiting. It is a memento mori that offers itself as a prayer of the gaze, a contrition that gazes at the implacable horizon of events, and gives the world a symbol of grief in which to immerse ourselves, the archetype of an affliction that unites humans of all ages and backgrounds.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) is now a mythical figure of the 20th century, she who was a child of the Mexican revolution, wife of the master Diego Rivera. She made headlines following an accident that paralyzed her at the age of 25 that confined her to bed, where she painted her surreal portraits and where she amplified her militant passion for freedom. Apart from the individual paintings, the moral volume makes the artist a symbol of resistance, and a current reference in the link between the heart and the political struggle. A figure with today a global myth, an icon for all women who have challenged horror with the poetry of a new visionary beauty. The real creative turning point for women came with the development of photography, the first modern emancipation that gave new roles and a newborn respect for a militant professionalism in a female key.

Gerda Taro (1910-1937), a German, companion of reporter Robert Capa, became a courageous photographer in the field, where she died at only 26 years old. She was run over by a tank in the midst of the Spanish Civil War. The black and white photos taken at the front in 1936 condense a compassionate gaze, a unique way of caressing lights and shadows, of capturing suspended moments, of feeling the collective tragedy that captured the pictorial, metaphysical, universal instant.

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American model of the 1920s, and later became a fashion photographer in Coco Chanel’s Paris. This is the cosmopolitan city where she began her relationship with the Dadaist Man Ray. For Vogue, she was a war reporter, documenting, among others, the Battle of Normandy and the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau. Her worldly life, her sensual and avant-garde presence, her bewitching power made her an icon of beauty and ethical commitment; an archetype of militant autonomy, who was at home in camouflage uniform as in a long gown for the grand soiree.

Catherine Leroy (1944-2006) was a French photojournalist of notable fame, who made headlines with her photographs of the Vietnam War for Life magazine. Hers is the story of a tenacious and resilient freelancer, who was ready to plunge into the heart of death, to release the truth of horror to the world through the Marian eyes of merciful pietas. She left for Laos in 1966 with a one-way ticket, and began working with Associated Press, until her name became a female synonym for Life, the magazine that consecrated her militancy in the most absurd war in American history.

Susan Meiselas (1948), an American from Baltimore, trained in Visual Education at Harvard. In 1976, she joined the Magnum group, and two years later, she flew to Nicaragua to document the Sandinista Revolution. Later she covered Chile during the Pinochet regime, and then followed events in Kurdistan, until her recent work on the lives of women in a refugee camp in England. There is a rare consistency in her gaze, a militant passion for minorities, a photographic narrative in which the female eye captures every nuance of pain, with that gentleness and firmness that only special beings have.

By Gianluca Marzian

A critic and art curator

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti