In Russia, the icon is considered a door; by meditating before it, one opens and reveals a presence. In the Western world, however, we speak of images that, when visualized, can open doors within ourselves. Our soul is often described as a door through which images can enter.

In contemporary art, it is interesting to note that the woman and the door seem to have a mysterious relationship. The Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi presents unassuming paintings, with minimal furniture, and always a woman placed in the rooms, far from any Vermeer-like familiarity. The woman is constantly near the door, standing still there, but never crossing it. A trick that gives the door a surreal meaning; it seems like just a constructed illusion. Gradually, discomfort makes its way into the viewer’s consciousness. The “gaze ahead” seems like a caricature. Hammershøi's images were created under the influence of the writings of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey. Hammershøi’s women read, clean, sew, and are often seen from behind, and never returning the artist's gaze. In this way, they illustrate one of the cornerstones of feminist theory: women are the object of the male gaze, they are constructed by it. The door is closed.

In the works of some female artists, the door becomes instead an opening, a place for inner exploration, as seen in the art of Franco-American Louise Bourgeois, Spanish artist Remedios, Cuban-American Ana Mendieta, and Colombian Doris Salcedo. They use doors to address political and social themes such as violence, migration, and memory. The door becomes a threshold.

The names of two artists who have broken all taboos while simultaneously managing to speak across different cultures are the Iranian-American artist Shirin Neshat, and the Afghan street artist, Shamsia Hassani. The former has used doors as symbolic boundaries between genders and cultures in her photographs and videos to explore the conflicts and connections between the East and the West. Her work acknowledges the complex intellectual and religious forces that shape the identity of Muslim women. Her photographs and videos feature women covered with Arabic calligraphy. The woman's body becomes a door to freedom.

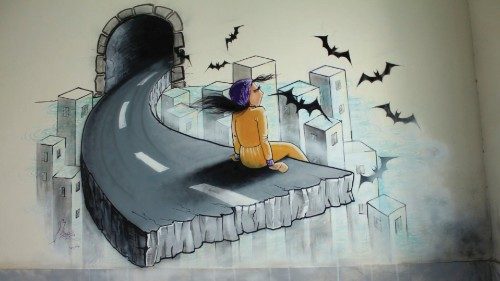

This phenomenon can also be found in the works of Shamsia Hassani. The artist is convinced that art is stronger than war. It becomes a door to peace. She creates imagined openings in walls; actual doors, gates through which one can enter. The walls open in a creative way and become a surface for projecting dreams and desires. Furthermore, it creates a bond that connects all cultures. The point of contact with European artists emerges, which sees emerge the melancholy of a voiceless world. We can say that her artworks break the iconoclastic approach of Islamic art. Her art is a door that lets in a sensitivity that creates irritation and destabilizes the male-dominated world. Almost cartoonish silhouettes, floating spirits emerging from the rubble. They have sharp, angular outlines, and under the burqa or hijab, there are real people, but with no trace of a mouth. The female figures seem traditional, wrapped in the traditional chador, but they belong to another world. Figures that cross the door to enter a new, unknown world, but one that promises a transformation in the color of freedom. Shamsia[AR1] creates titanical images in their effort to present themselves, to be recognized and accepted, speaking of other cities, of freedom, of demolshed walls, and flying streets. Shamsia says: “Art changes people’s minds and people change the world”.

[AR1]. Figures that pass through the door to enter a new, unknown world, but one that promises a transformation in the colour of freedom. Shamsia creates images that are titanic in their effort to present themselves, to be recognised and accepted, speaking of other cities, of freedom and demolished walls, of flying streets. Shamsia says: 'Art changes people's minds and people change the world'.

by YVONNE DOHNA SCHLOBITTEN

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti