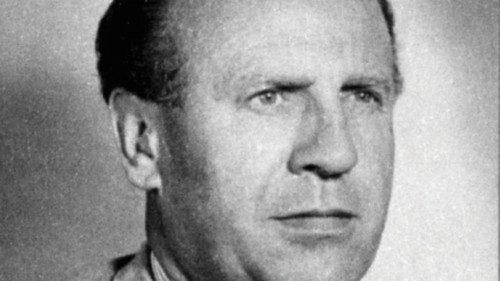

German businessman Oskar Schindler, who saved more than 1,000 Jewish people from being killed in the Shoah, died 50 years ago. In today’s world, torn apart by war and violence, this anniversary is like a beacon of hope.

Schindler did his duty. He was a businessman with two distinguishing traits: initiative and risk. From this point of view, he was a great businessman. He faced the dilemma that Danish philosopher Kierkegaard put before everyone when he wrote, “To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily. Not to dare is to lose oneself”. And he knew how to respond.

Perhaps, great people in history must be “off balance”. It was only this way that Schindler was able to strike the earth’s axis as it was lazily spinning on itself, redirecting him towards another horizon, one that was more humane.

Spielberg’s beautiful film shed a light on this story, and it had a positive effect. Indeed, especially today, with the world once again chipping away at all that is alive, good and human, we are in need of beautiful stories, rich in charity and hope. And it is comforting to think that the world is filled with stories of good that remain hidden, like Schindler’s story, before it was told by a movie.

On 27 March 2020, during the Extraordinary Moment of Prayer in Saint Peter’s Square, Pope Francis remarked that “our lives are woven together and sustained by ordinary people — often forgotten people — who do not appear in newspaper and magazine headlines nor on the grand catwalks of the latest show, but who without any doubt are in these very days writing the decisive events of our time”.

In The Splendour of the Church, Henri De Lubac spoke of Christians who live their lives, hidden from the eyes of the world, people who make the greatest contribution to ensuring that our world is not like hell, people who bring hope. It is the same intuition that spurred English author Tolkien during the same dark period in which Schindler dared to save lives, at the risk of his own, to write: “What is really important is always hid from contemporaries, and the seeds of what is to be are quietly germinating in the dark in some forgotten corner, while everyone is looking at Stalin or Hitler […] No man can estimate what is really happening at the present sub specie aeternitaris. All we do know, and that to a large extent by direct experience, is that evil labours with vast power and perpetual success — in vain: preparing always only the soil for unexpected good to sprout in”.

Schindler’s “sprout” was stronger than Evil because as the theologian, now cardinal-elect, Timothy Radcliffe has said, the “mystery of evil is great, but the mystery of good is greater still”. (A. Monda)

Andrea Monda

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti