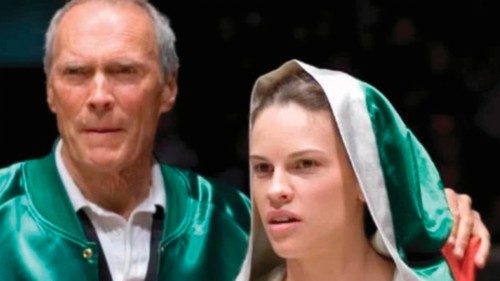

Is there a cinema that transcends the iconographic representation of Mary and can allegorically evoke her? Can we speak of a “figura Mariae” with the same significance as the phrase “figura Christi”? The latter expression has transitioned from literature to cinema and is commonly used to indicate the connection between a character and Jesus through the “figural interpretation” of events. Exemplary is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Joan of Arc in his famous Passion, or the heroine in Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves, or the protagonist in Paolo Benvenuti’s Puccini and the Girl, or the protagonist in Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby. The examples are endless and belong to a cinema that is not merely illustrative of biblical or religious themes, but transcendent and spiritual (allegorical). Masters of this approach include, in addition to the aforementioned directors, Robert Bresson, Roberto Rossellini, Yasujirō Ozu, Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader, Wim Wenders, and others.

However, let us return to the question: can we speak of a “figura Mariae” even in cinema? Can we identify some characters without the risk of falling into dull contrivances? Let us try to identify some characters whose narrated life journeys contain elements that evoke episodes from the Gospels about Mary.

The theme of motherhood is a symptomatic and eloquent element. Many stories of motherhood can be highlighted. The “sacrificed” motherhood of the protagonist in Mamma Roma by Pier Paolo Pasolini, the “painful” motherhood in All about My Mother by Pedro Almodóvar, and the “healed” motherhood through hope in Mommy by Xavier Dolan are all exemplary depictions, not mere figures. Allegorical motherhoods can be glimpsed in the stories of the protagonists in C’è ancora domani [There is Always Tomorrow] by Paola Cortellesi and The Story by Francesca Archibugi. In both cases, the actions of mothers willing to protect their children to the point of sacrificing themselves are inspiring, evoking the massacre of the innocents and the flight to Egypt. The mother in The Tree of Life by Terrence Malick is a woman who, despite the wounds that have marked her life (echoing the prophecy of the elderly Simeon or the silent prophecy of Anna), experiences love for her children by sharing her time with them, raising them, and defending them. She imparts to them a spiritual sense of respect and love for others that is stronger than anything else, as she stays close to her growing child.

Figura Mariae, much like Figura Christi, is the protagonist of Babette’s Feast by Gabriel Axel. With noble affability, Babette serves two elderly women, helping to restore harmony in a community in need of attention, and selflessly investing all her resources for the pleasure and well-being of her benefactors’ guests, evoking the Visitation. In Adam by Maryam Touzani, this figure can be seen in the baker who initially welcomes the young pregnant protagonist with suspicion but then with caring concern, there is a “reverse Visitation” as she accepts and supports the young woman rejected by others. Nomadland by Chloé Zhao can be interpreted as the Magnificat of the rejected and discarded, who have lost everything except ownership of their own person and feelings, which they mutually share in a discreet acknowledgment of their dignity: humble without pretense, and thus worthy of being “exalted” for the authenticity of their supportive relationships.

In Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers, an eccentric professor embodies a powerful Christi figure, the character of the cook with the evocative name Mary is in the background. In her sorrow as a mother who has lost a child, she is alive, attentive, and proactive (like Mary at Cana) in meeting the needs of the story’s other two protagonists, who recognize her life lesson through these qualities. Their unity generates the miracle of effective and creative solidarity; similarly, the characters in Aki Kaurismäki’s Le Havre achieve their goal by pooling their resources with the spontaneous generosity of the simple-hearted, believing in what they are partaking in, which is reuniting an immigrant boy with his mother across the English Channel. This sharing echoes that experienced by the early Christians with Mary, the miracle of communion after Easter. Lastly, in Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands, the character closest to Maria is Mrs. Peggy. Unafraid of a “boy” so different, she simply makes herself available not only to protect him but also to listen to such a special being who transcends human tranquility. She understands that this unusual and exceptional creature is extraordinarily gentle and in need of tenderness. Peggy comprehends and defends him, establishing a spiritual “correspondence of loving sentiments”. Those who listen carefully, even in the awareness of difficulties, manage to say “yes” wherever and however it may be required.

by Renato Butera

Priest, lecturer in Cinema and Film Languages at the Pontifical Salesian University in Rome - Cinematografo Magazine

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti