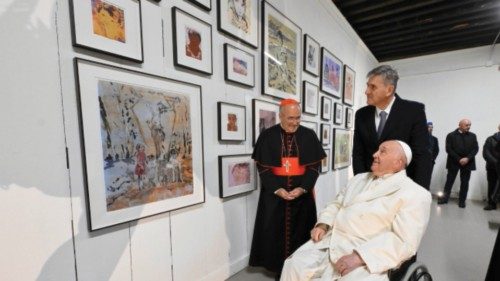

Meeting with artists in the Church of La Maddalena, the chapel in the Giudecca women’s prison in Venice, Pope Francis began with a confession, continued with an appeal and concluded with a question. “I confess that beside you I do not feel like a stranger: I feel at home. And I think that, in reality, this applies to every human being, because, for all intents and purposes, art takes on the status of a ‘city of refuge’, an entity that disobeys the regime of violence and discrimination in order to create forms of human belonging capable of recognizing, including, protecting and embracing everyone”. The decision to set up the Holy See’s Pavilion for the Venice Biennale inside the Giudecca women’s prison is a response to this vision of art. Art, the Pope reminds us, is a place where every human being can recognize him or herself and recognize the world as it was meant to be in God’s original plan, that world created and admired by its Creator: And God saw that it was good (Gen 1:18).

Art therefore can become a moment of relief, of respite, of escape from a frenetic life whose only aim is to produce, to do, to overwhelm. As with sport — we can think of the “Olympic truce” — art can create conditions for peace. “It would be important”, the Pope said, “if the various artistic practices could establish themselves everywhere as a sort of network of cities of refuge, cooperating to rid the world of senseless and by now empty oppositions, that seek to gain ground in racism, in xenophobia, in inequality, in ecological imbalance and aporophobia, that terrible neologism that means ‘fear of the poor’”.

Then he launched an appeal, addressed directly to the great talent proper to artists, namely, imagination: “I beg you, artist friends, to imagine cities that do not yet exist on the maps: cities where no human being is considered a stranger. This is why when we say ‘foreigners everywhere’, we are proposing ‘brothers everywhere’”. These “non-existent places”, to paraphrase J. Barrie’s novel, are a necessity, they are that city which makes all other existing cities humane and rich with meaning, because, the Pope strongly affirmed, “the world needs artists”. Christians themselves are called to be the artists the world needs. And they have been already, for some 2,000 years, because the paradox of living in the world simultaneously as “strangers” and “brothers” is embodied in the Christian every day. The ancient Epistle to Diognetus had already said it clearly and precisely: “Inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, [Christians] display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers”. Feeling at home and like strangers at the same time along the earthly pilgrimage is the paradoxical condition of Christians in the world who propose “a wonderful [...] method of life” to a humanity that is often distracted, bored and sluggish.

The world at times assumes the hard and inhumane face of prison, a prison from which one can escape, and art can present a path to this liberation, to possible redemption. This process of liberation can arise only from the heart of humanity and from its way of looking at the world and at life. This is why, to conclude his speech, the Pope turned to the Pavilion’s title, With my eyes: “We all need to be looked at and to dare to look at ourselves. In this, Jesus is the perennial Teacher: He looks at everyone with the intensity of a love that does not judge but knows how to be close and to encourage. And I would say that art educates us in this type of outlook, not possessive, not objectifying, but neither indifferent nor superficial; it educates us in a contemplative gaze. Artists are part of the world but are called to go beyond it”.

And then, lastly, the question: What do we see in our daily lives? How do we see the world? What are we ultimately looking for? The Pope recalls Jesus’ question to the crowds, regarding John the Baptist: “‘What did you go out into the wilderness to behold? A reed shaken by the wind? Why then did you go out?’ (Mt 11:7-8)”, and he invited artists to keep this question in their hearts. There is a desert today that is expanding in a world wounded by many wars, by the “cold” greed of a market that regulates and dictates, but there is also a well of fresh water, a refuge where men and women can meet freely, refresh themselves and continue their journey in this place — at the same time strange and familiar — which is the world, the good and beautiful world which the Lord, in his creativity, entrusted to us. (A. Monda)

Andrea Monda

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti