Test

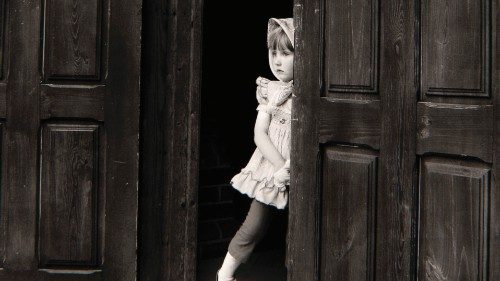

They used to sit in the right aisle, women with their heads veiled, white scarf for the unmarried, black for the married. Men on the left. It is now difficult to find churches where the rigid male-female distinction, in use before Vatican II, still persists. But for a girl, until the 1960s, going to Mass in the parish on Sundays meant receiving a non-verbal message of “positioning” in the community: you belong to the other half, there are spaces closed to you and defined roles. In the Church as in life. “During the 1970s, women removed the scarf and with the scarf also the veil in church”, comments Anna Scattigno, professor of Church History, feminist, member of the Italian Society of Historians. “It was the new climate of the Council and feminism. A silent but determined revolution, from which there is no turning back”. Today, the girls who serve during the Eucharistic celebration are one of the most evident signs of the progress made. However, there is still a long way to go.

The Gospel has “Good News” for girls: the message of Jesus is potentially a source of growth, empowerment, and full maturation of being. A ladder with which to surpass the walls - in terms of discriminatory social mechanisms or dysfunctional relationships - that they will encounter in their lives as women. However, the teaching imparted in the parish, in Catholic associations, in religious education classes, often goes in the opposite direction, ending up reinforcing stereotypes and bolstering feelings of inferiority compared to dominant masculinity. In fact, in the face of an extraordinary commitment to the promotion of girls in areas of the Global South where rights are severely limited, there is no in-depth reflection on their “gendered subjectivity”. That is, on how the female identity of little girls - shaped by the multiple interactions and conditioning they encounter from a young age in the family and social sphere - influences their way of relating to faith and to God. Ecclesial communities do not seem to have yet posed with sufficient force the question: what place should we give to girls? The question, as Rita Torti, of the board of directors of the Coordination of Italian Women Theologians and expert in gender studies, explains, implies another, crucial one: what women do we want these girls (and, correspondingly, these boys) to become? “From how we answer, ideas and educational practices and the transmission of faith emerge, but above all, the truth about ourselves. That is: what is our idea of woman (and, correspondingly, of man)?”.

The Spring of the Council

Vatican II marked a watershed moment also in the religious education of the youngest. The sacred space opened up, altar servers arrived. The branches of ecclesial associations came together for equal education. Above all, boys and girls became not just recipients but subjects. As Annamaria Bongio, national coordinator of Catholic Action for Children, says: “They are not the Church of the future but protagonists in the present, there is already a fullness, they are people, citizens, Christians now in the present even though still in the making”. The youngest branch of Catholic Action was born in the wake of the Council with a statute that valued how “all the laity and children included could put their co-responsibility into play”. Vittorio Bachelet, the then national president, was the father of Catholic Action for Children, the branch that united the aspirants, the favorites, the little ones, and the little angels, the youngest of the Female Youth (Gf) created in 1918 by Armida Barelli, with the male groups. The foundation of Gf had already represented a new fact: the members were invited to leave home and engage in action, breaking the barriers to which culture had subjected them. “The Christian mother and wife received from nineteenth-century tradition were proposed as a model of Catholic female militancy, but the forms of militancy induced a flexible use of the model”, concludes Scattigno. Similar ambivalence emerges from the contents of the press for the very young, which exploded in those years. Among the pioneering publications were “Squilli di Risurrezione” [Resurrection Rings], promoted by Barelli and divided by age group. Thirty years later, the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians gave life to “Primavera” [Spring], a magazine for young girls, and in 1955 “Così” [Thus] arrived, published by the Daughters of St Paul. “The education of ‘young girls’ became crucial as future mothers and therefore ‘potential’ educators of tomorrow’s citizens, but also ‘secret agents’ within families capable of bringing back to faith and the right path brothers and fathers who may have lost their way. For this very reason, the Church trusted in the potential of women”, explains Ilaria Mattioni, lecturer at the Faculty of Philosophy and Education Sciences of Turin. It is worth mentioning “Il Giornalino”, published by the Pious Society of St Paul since 1924, which immediately chose to address both girls and boys indiscriminately, anticipating, in some ways, another great novelty of the post-Council era: coeducation.

The challenge of an “ensemble” that doesn’t become unisex

“It would be unfair to train women differently from men according to a prior ideological approach, a natural, almost predetermined fate”, says Emilia Palladino, a lecturer in social sciences at the Gregorian University. “It’s right to educate them so that they know who they are, not who we want them to be. In fact, by predefining their identity, we strip them of immeasurable richness”. According to theologian Andrea Grillo, author of “L’accesso delle donne al ministero ordinato. Il diaconato femminile come problema sistematico” [The Access of Women to Ordained Ministry: The Female Diaconate as a Systematic Problem] (San Paolo), “when a ‘essentialist’ view of womanhood is proposed, projecting on one side onto Mary as the ‘all beautiful mother’, and on the other side onto the virginal vocation of every girl, with a dual ‘private’ reduction of both motherhood and virginity, then it is clear that the ecclesial imagery projects onto ‘woman’ and ‘every woman’ a life plan and a model of behavior that tends to confirm the stereotype that the male belongs to God, but the female belongs to ‘a’ male. She cannot emancipate herself because by nature she is a servant. To serve is noble, but when you choose it. If it’s imposed on you by ‘nature’, you have every right to doubt it”.

It is undoubtedly clear, therefore, that the end of separate education between males and females in associations, in catechism, and in the majority of Catholic schools, generally conceived from a defensive standpoint, has been an important step forward. It represents a sort of necessary but not sufficient condition for the emancipation of girls in accordance with the liberating message of the Gospel. Because sometimes in groups—where males and females stand side by side—a generally “neutral” faith is conveyed, a false unisex facade behind which a substantially male model is hidden.

“We start with an apparently trivial example. Despite the Catholic Church catechism stating that God ‘is neither man nor woman’, we say ‘God is good, God is a friend, God is close…’. This language creates a mental representation of God as male. Therefore, even without openly stating it, we instill in children the idea of being the same gender as God in boys and that God does not resemble them in girls. This activates two very different paths of faith”, explains Torti, author of the book “libro Mamma, perché Dio è maschio?” [Mom, Why Is God Male?] (Effatà). Unlike girls, boys do not immediately grapple with the divine otherness. “In children, the image of a male God confirms their dominant role. It’s an illusion of omnipotence they will pay a high price for, with perpetual performance anxiety and difficulty in accepting losses, defeats, and abandonment. For girls, however, not having the opportunity to see themselves reflected in the face of God constitutes a lack that inevitably conditions their perception of their own worth and deprives them of a fundamental resource to counter the devaluing gaze they will have to contend with”. Education in reciprocity is precisely the key to combating marginalization and violence. “And it must start from very early childhood. It is necessary to help children relate to others with respect for their differences. But we adults must first experience it ourselves”, emphasizes Sister Mara Borsi, head of the pedagogical-didactic area at the Higher Institute of Religious Sciences in Bologna. “Our relationship with differences is still a raw nerve. That’s why we tend to avoid it”.

Pedagogist Paola Bignardi, a collaborator of the Youth Observatory at the Toniolo Institute, speaks of a “culture of indistinctness” manifested in standardized education, which pays little attention to the needs of the individual, including gender characteristics. The failure to consider a specific feminine aspect in experiencing faith and spirituality during childhood means that in adolescence, when differences become more pronounced, girls struggle to find a place in the Church, conceived as essentially male. “At the pivotal age, between 16 and 17 years old, many girls abandon [the Church] with greater intensity than their male peers”, says Bignardi, author of “Dio dove sei?” [God, Where Are You?] and “Cerco, dunque, credo?” [I seek, Therefore, I Believe?] (both published by Vita e Pensiero). “The young women who self-identify as Catholics make up 33 percent, whereas in 2013 they were 61.2 percent. Over ten years, the proportion of those who consider themselves atheists has risen from 13 to 30 percent”.

On the side of the girls

Since its establishment in 1974, the Catholic Guides and Scouts Association of Italy (AGESCI) has uniquely addressed the tension between equality and difference. The choice of coeducation from childhood onwards—understood, as explained in its statutes, as “a path of growth that, starting from the identity of being male and female, leads to the discovery and knowledge of the other”—has been combined with that of a diarchic leadership. “From the youngest groups to the older ones, there is always a dual leadership, comprised of a woman and a man who work together on their education. The idea is to offer children and young people, from early childhood, a model of authority characterized by a collaborative male-female relationship”, explains the president, Roberta Vincini. “This approach aims to educate in welcoming and respecting diversity, starting from listening to each individual child”.

Listening and personalized attention are also the starting point suggested by Bignardi to build an education for life and faith that truly meets the expectations of girls. The journey continues by making space in ecclesial communities, says Torti, “for the image that a girl, confirming the need for reflection, spontaneously drew and described during a workshop, ‘God in a skirt’. But God reveals Himself to us in his Word, and so it is essential to narrate this Word, returning to it what has been overshadowed or distorted over many centuries—and often even today. In the Bible, despite being texts from distant times, there are female figures that play a fundamental narrative and theological role (the matriarchs, the prophetesses, and other women of the Old Testament, and then in the New Testament, the disciples and the women encountered by Jesus, the protagonists of some parables, and the women of the early Christian communities). It’s not about creating a ‘Bible for girls’, but about narrating in its entirety a story in which God reveals Himself to both women and men and acts in the folds of women’s lives as well as men’s; and in which Jesus never asks women to ‘stay in their place’. Because God is also on the side of girls”.

by LUCIA CAPUZZI* and VITTORIA PRISCIANDARO**

*Journalist for “Avvenire”

**Journalist for “Credere” and “Jesus”, Periodici San Paolo

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti