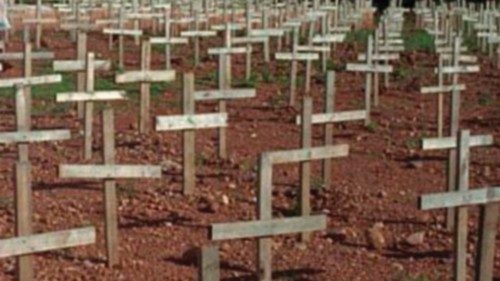

On Sunday, 7 April, Rwanda commemorated 30 years since one of the most bloody episodes of the 20th century. Nearly one million people, mostly ethnic Tutsis, but also moderate Hutus, were exterminated in 100 days, between 7 April and early July of 1994, in a wave of violence triggered by fratricidal hatred.

The genocide perpetrated by Hutu rebels still stands out today for its ferocity and speed, and for the international community’s inability to prevent the violence. The world watched, dumbfounded, as decapitations were broadcast on television, while the French-led Turquoise operation launched by the UN and the Unamir mission proved powerless.

The horrendous killings were triggered on 6 April 1994, when the plane carrying Hutu President Juvénal Habyarimana, was shot down by a missile as it was preparing to land at the airport in Kigali. Those responsible for ordering the attack have not yet been identified.

Reconciliation is a top priority for the “land of a thousand hills”. “The Church in Rwanda for 30 years now has been a pastoral ministry of reconciliation”, explained Cardinal Antoine Kambanda, Archbishop of Kigali, in an interview with Vatican media. “The genocide was the result of a long ideological history”, he noted, resulting from a “politics of division” prevalent in the years leading up to the terrible events of 30 years ago. Today, as opposed to then, identification cards in Rwanda no longer indicate a person’s ethnic group. In the past, the situation “also led to divisions within families themselves”, the Cardinal continued, explaining that in cases of “mixed” families, the child’s ethnicity was determined by the father’s which “led to incredible tragedies”. Indeed, he underscored, it was “a genocide that affected the most intimate human relationships, even within families”.

The commitment to reconciliation has spread to schools, many of them Catholic. “There is no need to focus on ethnic differences but to identify as Rwandan and thus, as brothers and sisters with the State that abolished the ethnic equilibrium”, affirmed the Archbishop of Kigali. The history of the genocide is taught in an academic programme which is strictly controlled by the government: today, more than 70 percent of Rwanda’s 14 million inhabitants are under 35 years old, and, not forgetting the past, they seek to free themselves from the burden of a genocide they did not experience. The reconciliation promoted by the Catholic Church transcends Rwanda’s borders. Kambanda mentioned a peace initiation programme set up in the Great Lakes region. The latest meeting was held in Goma, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “There is a need to understand that differences are a wealth and a resource”, he affirmed.

Justice, too, is important in the process of turning a new page: in particular the local courts, called “gacaca”, have played a part in fostering reconciliation among communities. The results of the ad hoc international Tribunal created by the UN were limited, and, according to Kigali, hundreds of people suspected of having participated in the genocide are still free, especially in neighbouring countries.

As it reconciles with the present legacy of the past, today Rwanda is one of Africa’s most dynamic economies. Its gdp has grown by more than eight percent, and Kagame has solid ties with Western countries,

While it is difficult to deny that the Kagame era has promoted stability and economic development in post-genocide Rwanda, one cannot ignore the fact that the country’s historical legacy has made it a less vibrant democracy. Various ngos denounce the lack of freedom of the press and the absence of a true political opposition. The upcoming elections on 15 July will test this, as Kagame will practically run without any rivals, and the latest constitutional amendments will grant him the possibility to remain in power until 2034.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti