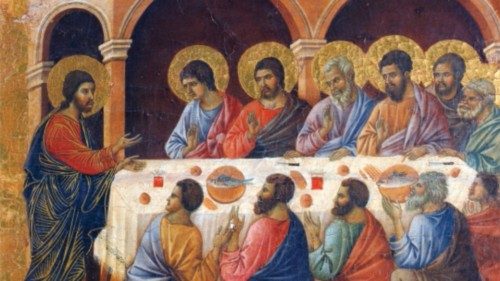

“Peace be with you” are the first words that Jesus addresses to the apostles who had shut themselves in the Upper Room in fear. Peace. Today more than ever, this word resonates, moves and upsets profoundly. To say “peace” today is like discovering and pointing out to others the presence of a drop of water in the desert, in the desert of a world that is locked in fear and mistrust, and that continues to be lacerated by winds of sand and anger, that wind of war that abides and upsets the heart of man, from the time of Cain.

Lack of peace is not only visible on the maps of military strategists, but is firstly visible in our hearts. And there is no place on the world’s maps that is exempt from this lack. There is no “safe” place. Wherever men and women are, they coexist with this source of violence that springs “from within”.

The battlefield on which evil and good fight is the heart of man, as Dostoevsky wrote and as Francis tirelessly reminds us, with the courageous trust that the conversion of hearts is possible and is the key to reach the horizon of peace. In the same way, in a reflection on the Passion according to Matthew, Jesuit Fr Silvano Fausti clearly sensed and highlighted that Jesus was not betrayed by his enemies but by his friends and that Judas did not have a script he had to follow: “It wasn’t up to him to play ‘the role of Judas’ […] It is written because we do this, not because God has predestined us; it is written that from Cain onwards, we kill our brothers and sisters, we live off of violence. The Scriptures are a chronicle. So is our history […] So the Son of man restores our humanity which is not violent, in which all violence ceases. He bears all the violence of our inhumanity on his cross. This is written. Therefore, Judas does not commit a strange sin, he commits the sin we all commit: it is the sin of the world in which we all have our share of ownership, he bears upon himself our violence and it is so serious that it is better not to have been born rather than commit it. That is, that violence is the destruction of man. It is hell, and Jesus comes precisely to save us from this”.

The unprecedented proposal of Jesus, who descends into our hell to bring his heaven, calls man to respond to it freely, without any pre-established script to be obeyed. In order to do so, he must believe that evil can be eradicated from the heart, believe in that drop of water that surprisingly gushes forth in the desert and saves him by bringing new, fresh life that springs and sings because it no longer fears death.

This Easter hymn is the joyful task, the light yoke, the bright destiny of Christians.

(A. Monda)

Andrea Monda

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti