Judaism

The prayer of Jewish women is a rich area of inquiry within Jewish literature, stirring numerous complex questions. Its roots stretch back to ancient times, with the Torah offering glimpses into its beginnings. One of the earliest recorded instances is the song of Miriam, accompanied by a chorus of women dancing and playing tambourines, following the crossing of the Red Sea by the Israelites (Exodus 15:20-21). Yet, there are at least two other notable women who offered songs of praise to the Lord in a manner unprecedented by men: the prophetess Deborah, after the victory over Sisera (Judges 5:1-31), and Hannah, who fervently petitioned the Lord for a child (1 Samuel 1:13). Following Hannah’s silent plea, wherein her desperation was only evident in the movement of her lips, came a subsequent prayer of gratitude for the birth of her son Samuel, the future prophet. This prayer, echoed throughout the centuries by women in the diaspora seeking children, draws parallels with the supplications of barren matriarchs, starting with Rachel (Genesis 30:6).

From the earliest times, therefore, women’s prayer played a significant role, both in the public and private spheres. The prayer’s were characterised by personal themes and styles, taken up by Jewish women in the centuries to come.

In addition to the prayers of praise and supplication of ancient memory, there are also those related to mitzvoth (commandments) specifically addressed to women, just as men are reserved others whose performance must take place at a specific time or part of the day. Thus, for example, women are not obliged to wear talleth or tefillin (both liturgical accessories) precisely because they are mitzvoth linked to specific times of day. However, there are exceptions where women also perform liturgical commandments at specific times: participation in the Pesach seder, the reading of the Meghillat Esther at Purim and the lighting of the Channukkah lamps. To these is added the prayer associated with the lighting of the candles on Shabbat, the first holiday mentioned in the Torah and first observed by the Lord himself (Genesis 2:3). It is the woman of the house who has the honour of performing this mitzvah, unlike the man who welcomes the Shabbat by participating in prayer in the synagogue. As explained in the Talmud, the woman has the privilege of welcoming the Sabbath in her home.

My Mother Blesses the Candles by Lithuanian-born artist Antoinette Raphaël (1895-1975) is probably the most representative painting of this intimate, domestic female moment. The work, created in 1932, freezes the most solemn moment of the Jewish woman at the moment when she lights the candles that consecrate the entry of Shabbat. On the canvas, Antoinette Raphaël expresses a double homage, to her mother Chaya and to the tradition that became the solid base and foundation of her future, the emblem of a religion that would be transformed in the course of her life from commandment to memory. The work offers a moving glimpse into female tradition and spirituality within the Jewish family. The figure of the mother perpetuating this ancient ritual represents a deep connection to the history and culture of the Jewish people, transmitting values and identity across generations. At the centre of the image is the figure of the mother, whose face is illuminated by the light of candles symbolising the sacredness and tradition of Shabbat. Her hands are raised in a gesture of prayer, while her gaze seems absorbed in the profound meaning of this ancient ritual, representing the moment of spiritual connection and gratitude to the Creator for the gift of shabbat. His hands raised in a gesture of prayer, while his gaze seems absorbed in the profound meaning of this ancient ritual, represents the moment of spiritual connection and gratitude to the Creator for the gift of Shabbat. The detail of the window in the background from which one glimpses the setting sun, the moment when daylight gives way to night, emphasises the temporal significance of the candle lighting ceremony that marks the beginning of holy rest and spiritual renewal. Overall, Antoinette Raphaël’s work masterfully captures the essence and beauty of such a significant moment in Jewish life, conveying a sense of peace, continuity and devotion.

From the domestic and intimate dimension, which makes women's prayer a private and individual moment, we pass, again through art, to the public and synagogal dimension where women, as we have already said, have no formal obligations. Yet, womens’ presence, when provided for, is anything but marginal.

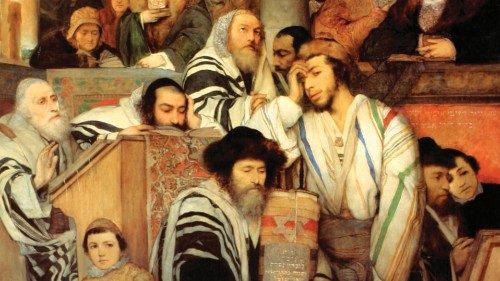

Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879) produced one of the most representative paintings of his young life in 1878, a year before his premature death. The painting depicts Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur, which today is conserved at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. The artist, who was one of the major protagonists of Polish Jewish painting, succeeded in capturing on the large canvas with extreme skill all the solemnity of Yom Kippur, a solemn occasion in which the Jewish people are called upon to make teshuvà (literally “return”, understood as repentance) through a 25-hour fast accompanied exclusively by prayer. Although the work revolves around the image of Gottlieb himself, who depicts himself in three different moments of his life, the women portrayed in the background, in the women's gallery, appear in all their scenic presence. In the procession of faces, we can also glimpse the artist's beloved woman, Laura Henschel-Rosenfeld, who appears twice within the narrative. In the top left-hand corner, she is depicted standing with her gaze turned towards the viewer, as if interrupted and distracted by our presence for a moment. She holds the prayer book tightly to her chest, her fingers between the pages so as not to miss the mark. We find her again on the right, in a completely different attitude, with her gaze bent towards another woman to whom she is whispering something. It is probably the mother who, despite looking towards us, is engrossed in reading the book she is holding. The harmonious balance of the large canvas is due to the pyramidal arrangement of the male figures that gives the painting a sensation of stability and visual order also dictated by the strong symmetry of the composition, traced by the column that continues in the image of the Sefer Tà held by one of the bystanders. This arrangement is counterbalanced by the horizontal placement of the women who appear behind, but higher up than the men in the foreground. This balancing act, in addition to giving an overall harmony to the structure of the work, could conceal a deeper meaning, where the woman's prayer is perceived by the artist as an indispensable completion, not only for the liturgical function, but for man's very existence.

Having said this, we have seen how female domestic prayer assumes a more complex function than public prayer. After all, according to the Torah, the public sphere is that of compromise, where the person is led to assume a role, as if to put on a mask. If we recall one of the most famous Jewish heroines in history, Esther, whose name means “hidden”. Having entered the court and heart of the Persian king Ahasuerus from whom she had concealed her identity, Esther invoked the Lord to save her people from Haman’s deadly plan.

In conclusion, the analysis of Jewish women’s prayer through the artworks of Antoinette Raphaël and Maurycy Gottlieb offers us a fascinating perspective on the duality and complexity of this aspect of Jewish tradition. From ancient silent entreaties to public expressions, the fundamental role of women in the domestic sphere and in bringing up children emerges. Through practice and memory, women's prayer thus becomes a bridge between past and present, uniting generations and emphasising the multi-millennial continuity of the covenant with the Lord.

by Giorgia Calò

Director of the Jewish Culture Centre of the Jewish Community of Rome

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti