InOpening

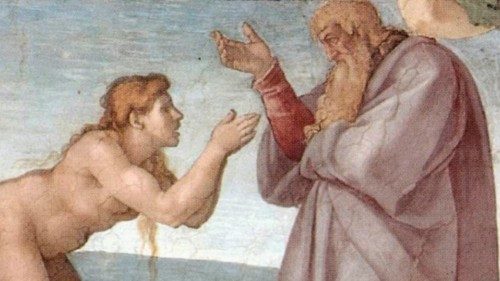

The earliest recorded utterance of a woman in Scripture is Eve’s unwitting reply to the serpent; the subsequent is her acknowledgment to God, admitting to being deceived. The third significant word, symbolically speaking, is the expression of gratitude directed towards God, emerging from the profound experience of motherhood. It is through this motherhood that Adam's renaming after the pivotal events in Eden finds tangible expression.

“The man called his wife’s name Eve, because she was the mother of all living” (Gen 3:20).

This third word is a cry - one does not know whether out of astonishment, or of victory - like a prayer: “I have gotten[a] a man with the help of the Lord” (Gen 4:1). Redemption from death, from the pains of childbirth (Gen 3:16; Joh 16:21), from all subjection.

At the culmination of the salvation narrative stands Mary of Nazareth. Throughout sacred Scripture, her speech is characterized by prayerful words; even her questions to the angel, her gentle reproach to her teenage son, and her observation of the lack of wine at the wedding are expressed as supplications. It is precisely through this constant state of prayerful “being” that Jesus acknowledges her as a woman (John 19:27).

In a remarkable instance, Mary unveils her hidden experience of motherhood through a prayerful song, resonating with psalmic expressions. The Magnificat unfolds as a magnificent tapestry of prayer, intricately woven with familiar psalmic motifs. Thus, amidst the triumphant cry of victory from the mother of all the living and the joyful melody of the young maiden from Nazareth, echoing through the hills of Galilee and the mountains of Judea, the entire saga of salvation, where women are traditionally instructed to “keep silent” (1 Corinthians 14:34), is illuminated by the fervent prayers of women who, through song, draw near to the Divine.

In the face of the harshest adversities and even amidst circumstances seemingly furthest from dreams and possibilities, women turn to prayer and song. They recognize that the most authentic “Thou” to their suffering and joy, to their anguish and hope, is none other than the Most High, their “Go’el” (Luke 1:46), intimately bound to the very essence of their human existence.

An experience deeply resonant with these devout women, one I am certain of after sixty years of monastic life, is at the very core of women's monasticism. It is the profound encounter with prayer, gradually unfolding and embracing the entirety of the human essence. Day after day, amidst weariness and drowsiness, they find themselves permanently immersed in the cadence of psalmic words, enveloped by the rhythm of life within the monastery.

Each day, as I enter the choir and settle into my seat, I am met by the solemnity of the 14th-century fresco depicting Jesus' prayer at Gethsemane, with the three sleeping disciples beside him. Their silent bewilderment resonates within me, echoing the discomfort of not knowing how to keep vigil—a timeless dilemma that pierces through generations and touches me deeply. In the midst of this contemplation, arises the persistent question, the essence of every genuine prayer: “Teach me!” (Luke 11:1).

It was an extraordinary day, perhaps even epochal, though not precisely recorded, when the collections of psalms spanning different eras, spiritual traditions, and generations were acknowledged by the faithful community—possibly beginning with small groups of exiles—as the inspired work of the Spirit of God. Thus, the Psalter was officially incorporated into the canon.

Here lies the essence of faith-filled prayer—a truth that, as a member of a community of women nuns, I earnestly pursue and integrate into my life. Six decades of immersion in the psalms do not diminish, but rather deepen this realization: in our collective recitation of the psalms—especially when done together, even in solitude—God communicates with God. Countless thinkers, including Augustine, have illuminated this profound experience with timeless words; he has opened the door for us.

More recently, I came across a poignant expression of a shared experience we all have, articulated by a woman—excerpted from a letter by Cristina Campo to her friend Mita. In it, she eloquently portrays her encounter with psalmody, beginning with her participation in a monastic celebration, where she, a solitary woman and a poetess of profound sensitivity, found herself deeply moved:

“In the Psalms we find everything, my story and hers, and everything wonderfully cast in God’s lap, an enormous diary of the whole man written for God’s eyes alone”. And, a little further on, she writes: “I would very much like you to discover in the Psalter a secret that only in these days has become clear in my mind: how it is prayer that makes everything, and man is, as always, but a vessel en ypoméne. It is prayer that slowly takes hold of man, not the man of prayer, it is she who drinks the man and quenches his thirst, and only in the second instance is it reciprocal. The expression ‘absorbed in prayer’ is literally correct. The method, the constancy required, is only to produce the emptiness that makes this absorption possible. It is as in the Supper: ‘Desire thou didst desire...’. It is he, [God], who first hungers for us. It is prayer that wants to be prayed for, that is, nourished by us”. “[...the Psalter] which is perhaps not a book to be read only in the evening and in silence. On the contrary, I believe it is the book that should create for us everywhere, according to our fidelity, evening and silence. This we learn slowly”.

On the opposing bank of the river of Psalms' prayer—a river that often plunges into hidden karstic paths only to resurface through the hearts of those who immerse themselves in its flow—a woman of Jewish descent, drawn to the Psalter through Kabbalistic mysticism, shares her revelation of its “ecumenical” essence in prayer: “I fell ill with the Psalms about ten years ago. I confess, I can no longer do without them! [...] Their language and their unsettling beauty accompany my awakenings and my nights. I search behind the veil of their words for ever new understandings and loves. [...] We are thus thrust, unwittingly, into words that shape us [...] fostering a new capacity to see and hear [...]. The Psalms: one of the threads that have sustained the most profound transformations of which men and women are capable” (Olivia Flaim, La danza di Davide. Dalla lettura dei salmi alle lettere del cosmo, [The Dance of David. From the Reading of the Psalms to the Letters of the Cosmos], Ghibli Editions).

Her insight rings true, resonating even within the humble confines of monastic life: engaging with the Psalms in their entirety—speaking, reading, reflecting, memorizing, singing, and even playing them—constitutes a pathway to personal transformation that imbues life with deeper significance. It enriches not only our existence but also our life in faith.

In praying the psalms, everything starts from the willingness to immerse oneself, to renounce a narcissistic spiritualism; to discover the “baptismal” dimension of prayer. Prayer is always a surrendering of one’s control over one’s life.

However, it is not mere capitulation; rather, it is a surrender to the Divine recognized as “the Most High, my Savior” (Luke 1:47). The relinquishment of control takes on the hue, resonance, and fragrance of trust, as articulated by Thérèse of Lisieux: “c’est la confiance.” Following in the footsteps of Jesus, at the core of this entrustment lies the spiritual practice of psalmody, fostering the growth of a consent to bear within oneself the narrative that binds us to the ultimate emblem of human destiny— “I bear in my womb the reproach of many nations” (Psalm 89:51). It is the calling of the Chosen One, the Messiah.

The collective practice of chanting -spanning days, hours, and moments-, gains profound resonance when viewed through the lens of years and decades of communal living. This perspective amplifies the insight of Isaac the Syrian, a sixth-century monk, who urged against fixating on the length of the divine office, the extent of prayers, or the repetition within them. He asserted that these elements are not the end result but rather the foundation of prayer (Centuries, IV. 70). In essence, immersing oneself in the prayer woven into the river of the psalms demands enduring patience—what Cristina Campo aptly terms as “en hypomonè” (cf. Luke 8:15)—a patience that allows for the “saving of one's soul” through its surrender. This patience, as taught by the patriarch of monasticism, involves attentively adhering with the mind to the voice” (Rule to Monasteries, St Benedict of Norcia, c. 19,7) through the attention of the heart.

The transition from root to fruit exemplifies an exquisitely feminine art—a narrative echoed in the events at Philippi. There, amidst the turmoil of fractured history and diaspora, during a shifting epoch, devout women along the riverbanks, led by Lydia, ushered in the Gospel’s transformative freshness, opening Europe’s threshold—a once glorious yet declining cultural space—to renewal. They mend fractured relationships and unlocked doors to unjust confinement, guided by the spiritual resonance emanating from the prayers by the river (Psalm 137:1).

The journey “from root to fruit” embodies the convergence of physical and spiritual realms, where the wisdom of the heart matures through the rugged roots of the psalms. Here, humanity pulsates with all its passions—nights and dawns, deaths and rebirths. Did not Jesus himself commence and culminate his earthly journey by learning from and praying with the words of the psalms? The daily communal recitation of the psalter, coupled with devoted study of its texts, cultivates within the female monastic community—a community devoid of ordained ministries yet rich in the baptismal priesthood—a transformative intimacy, fostering a genuine “living together” experience.

However, the spiritual vitality of aligning the mind with the voice extends an invitation for the heart's freedom to embark on an alternative spiritual journey, one entirely foreign to the prevailing culture of our laborious and intricate era—the culture of selfhood. Indeed, this dynamic finds resonance in the axiom of monastic spiritual wisdom applied to the psalms, challenging the simplistic formulas of various spiritual ideologies:

“He who in a superficial way reads precious syllables, makes his heart superficial and deprives it of that holy power that gives the heart the sweet taste of those teachings, which are capable of provoking wonder in the soul” (Isaac of Nineveh).

The wonder and agility cultivated through the diligent immersion in the psalter demand the characteristic skill of a “maternal” humanity. Such humanity is capable of embodying “the refuge of the desolation of peoples” (Psalm 89:51), while also possessing empathetic hearts that nurture every seed of hope (Psalm 131:3) until it blossoms into maturity.

In essence, we can distill the overarching framework of a protracted and deliberate life journey by acknowledging that the stance of the choir of psalm-singing nuns mirrors a profound alignment and yearning for the complete truth encapsulated in a revealing psalmic verse, appearing only twice in the entire psalter (Psalm 42:9; Psalm 109:4). This verse signifies the aspiration inherent in every whispered or sung verse shared together:

“... and I am prayer”.

by Maria Ignazia Angelini

Benedictine nun at the Viboldone Abbey, Milan

#sistersproject

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti