DifferentWaysofSeeing

On Via Toledo, the bustling heart and oldest thoroughfare in Naples, human traffic never ceases; it’s only after three in the morning that the flow begins to dwindle. A friend, residing near one of the narrow alleys branching from the Quartieri Spagnoli onto Via Toledo, a bustling neighborhood, laments, “I can hardly step out the door without getting caught up in the bustle”. Walking along Via Toledo, no matter how brisk your pace or focused your direction, you inevitably find yourself impeded or redirected into alcoves, swept into side currents that pull you off course, or ushered into squares or storefronts.

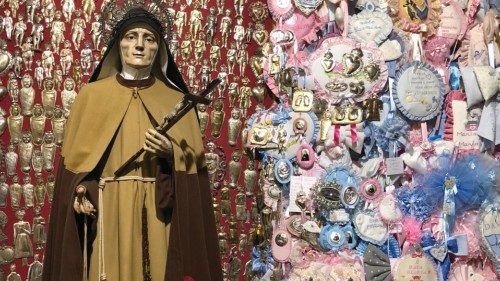

As you navigate the bustling streets, seeking respite from the throng, you might find yourself turning into an alley within the Quartieri Spagnoli, vico Tre Re, where, at number thirteen lies the shrine house of Santa Maria Francesca delle Cinque Piaghe. She was the first woman canonized in Naples and is revered as a co-patron saint of the city. Within this unassuming abode, consisting of three rooms reminiscent of a typical 19th-century dwelling, adorned with period furnishings, lies a small chapel and, most notably, a devout congregation of worshippers, predominantly women. This is because the cult surrounding Maria Francesca centers on miracles attributed to fertility and childbirth. Visitors seeking her grace often sit in her chair, which has become a symbol of hope for conception.

Maria Francesca, born in 1715 as Anna Maria Rosa Nicoletta Gallo, the daughter of a merchant couple, consecrated herself at the age of sixteen to the Third Order of St Francis. Despite remaining semi-literate throughout her life, she exhibited incessant gifts of prophecy, visions, and ecstasies. She quickly became a reference point for men of learning and church leaders, and her vocation proselytised uninterruptedly until she died, on 6th October 6, 1791.

Remembered as the holy virgin of the stigmata, she spent thirty-eight years in the house caring for charitable works and performing numerous miracles. it is no coincidence that she was present in the Quartieri Spagnoli, which, while the future saint was still a child, had been evacuated but which, from 1501 to 1701 under Castilian rule, were a notorious site for quartering troops and a place of prostitution.

The “santarella” [little saint], as she was called as a child, walked through these alleys, very similar to how we see them today. The chair on which women sit today, desperately awaiting children, is the chair where she spent the day afflicted by the burns of the stigmata and many illnesses. Sitting there, she predicted sanctity to Francis Xavier Bianchi, another saint to whom Naples was once very devoted. At her funeral there was a crowd: everyone wanted a relic of the saint and the public force was needed to stop the riots.

The Daughters of Saint Mary Frances, a congregation founded in 1884 by Brigida Cuocolo, at the request of Cardinal Guglielmo Sanfelice, after a troubled history concerning the use of the three rooms, still look after the tiny sanctuary. Even today in the Spanish quarters, the Daughters of the Saint are “our nuns”: Maria Francesca’s heirs look after children and young people in kindergartens, schools and workshops. The feast, held every year on the day of her death, remains a real event for the people of the district. Among the posthumous miracles, a plaque on the wall of the sanctuary recalls the one hundred and five bombings carried out on the city during World War II that the Spanish quarters escaped, always and without exception, thanks to the saint.

The prayer of women to a woman, however, is the most relevant aspect of this very popular faith, alive despite the obvious change in times and culture. A woman who acts as an intermediary with Mary, a woman who can understand women's problems, whether they are daughters, mothers, or, as they used to say, “bizzoche”.

“Eyes downcast and heart contrite the ‘bizzocca’ wants to get married”, so goes an old proverb.

There were, indeed, once the “bizzoche,” young women with little education and no means but with excellent spiritual fathers, destined to fulfill the role of Christian laity, deeply engaged in charity work and so strong in their vocation that they eventually became recognized religious figures by the church, authorized to practice monasticism within their own homes. The “bizzoche.”

If in popular Italian language the term “bizzoca” is derogatory, indicating a limited view of the world, it is important to remember that from the Council of Trent onwards, it was precisely the so-called “bizzoche” who embodied the active soul of Catholicism and charity, especially in southern Italy. These young women -who are now very elderly-, could still be encountered until a few years ago, were highly knowledgeable in Latin, that is, in formulas learned during years of non-Italian Mass, while rigorously following the ritual. These were women, who above all, in times of absence of free female choices, made, in their own specific way, an independent choice: outside of financial dependence, outside of marriage, sometimes forced by social conditions, others in rebellion against family and conventions, led their lives outside the control of the official patriarchy.

Saint Mary Frances of the Five Wounds is among the ranks of this army, which in Naples boasts women of learning and remarkable mystics. Among them is Anastasia Ilario, a Dominican tertiary, revered as the saint of the picturesque Posillipo district overlooking the sea. Maria Angela Crocifissa (Maria Giuda) hails from the proletarian Mercato district, an area with a history of executions and commerce. Prudenza Pisa, also known as Tenza, later became Sister Serafina of God, a mystic from Capri. Maria Landi, born in Naples on January 21, 1861, and an Alcantarine tertiary, is also counted among them.

Maria Landi was twenty-six years old in 1887 when, by special permission of Cardinal Sanfelice, while continuing to live in her home, she took her solemn vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and decided to consider herself de jure and de facto a nun, taking the name Maria di Gesù.

Mary must have been a remarkably active and intelligent woman, despite her limited formal education. Her selection for this task was not only based on her spiritual merits but also on the organizational skills she demonstrated in charitable works. Thanks to her abilities, we have the Basilica Incoronata Madre del Buon Consiglio, which was erected over a forty-year period (1920-1960) beneath the Royal Palace of Capodimonte. This basilica serves as a visual and spatial reference point visible from every part of the city facing the hills. Mary’s influence also extended to miraculous interventions, such as the interruption of an epidemic and the mitigation of a Vesuvius eruption in 1884. Despite the painter Raffaello Spanò's struggle with cataracts, Mary commissioned him to create a new image of the Madonna. Cardinal Sanfelice, displaying remarkable intuition, assured both the painter and the commissioner that the Madonna herself would guide the process. Remarkably, as soon as the completed painting was unveiled, a miracle occurred: Landi’s residence, located in Largo San Carlo all’Arena, was amidst a cholera outbreak, yet upon the Madonna’s appearance, the epidemic ceased.

One can only imagine the profound impact of such a remarkable event. In 1906, the Landis relocated to a larger residence at Via Duomo, 36, where they erected “a small but opulent oratory adorned with stuccoes embellished in delicate gold”. It was during this year that Vesuvius erupted in a famous and devastating event. On Good Friday, Sister Landi bravely exhibited the Madonna on her balcony, even as roofs and buildings crumbled under the weight of ash in the city below. Miraculously, a ray of sunlight pierced through the somber veil of ash, and the Vesuvius Observatory soon reported that the eruption was beginning to subside.

Needless to say, Via Duomo was teeming with a diverse crowd: noblewomen, postulants, casual passersby, and devoted pilgrims of all sorts, fervently seeking favors and offering prayers. Recognizing the significance of the occasion, Pope Pius X bestowed the honor of crowning the painting to Our Lady on March 29, 1911. The ceremony sparked a continuous stream of pilgrims flocking to the city for eight consecutive days, with pilgrimages and celebrations continuing unabated for years, particularly during the period of the First World War.

In short, with the saints, Naples has its own special devotion, archaic and solid: the Byzantine Patrizia, after all, is the first and has been shedding her blood since well before Saint Gennaro.

In essence, Naples holds a unique and enduring devotion to its saints, a devotion that is both ancient and steadfast; after all, the Byzantine Patrizia predates even Saint Gennaro.

by Antonella Cilento

Writer and teacher of creative writing, director of Lalineascritta Writing Workshops

#sistersproject

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti