In theScriptures

Prayer takes various forms, from exultations such as Deborah’s song (Judges 5) and Mary’s Magnificat (Luke 1.46-56) to laments from the “daughters of Israel” who weep over the impending sacrifice of Jephthah’s daughter (Judges 11.40) and the “daughters of Jerusalem” who weep over the impending crucifixion of Jesus (Luke 23.28). People needing healing and rescue pray, as did Hagar who said, “Do not let me look on the death of the child” (Genesis 21.16) and the Canaanite woman who, kneeling before Jesus, said, “Lord, help me” (Matthew 15.25). The Psalms, which are prayers, range from thanksgiving and celebration to intercession, petition, and contrition.

The Bible frequently states that men pray: Abraham (Genesis 20), Isaac (Genesis 25), Moses (Exodus 8, 10; Numbers 11, 21; Deuteronomy 9), Samuel (1 Samuel 8), Elijah (2 Kings 4); David (2 Samuel 7, 15, 24), Elisha (2 Kings 6); King Hezekiah (2 Kings 19-20; 2 Chronicles 30.), Isaiah (2 Chronicles 32), Jeremiah (Jeremiah 42), Nehemiah (Nehemiah 1-2), Daniel (Daniel 9), Jonah (Jonah 2, 4), Judas Maccabaeus (1 Maccabees 7.40), Tobit (Tobit 3.1); Job (Job 6, 42), Jesus (Matthew 26//Mark 14 etc.), Cornelius (Acts 10), Peter (Acts 11), Paul (Acts 22, 26), and so on. Luke 18.1 tells us that the Parable of the Widow and the Judge is meant to encourage us to “pray always and not lose heart.” When the people of Israel pray or when the members of the church pray, women are among them.

But the only women the Bible explicitly mentions as praying are Hannah, Esther, Judith, and Sarah in the book of Tobit. Their prayers are as diverse as the women in the Bible, for there is no singular way that women pray. Hannah appears in 1 Samuel, a text that both Jews and Roman Catholics consider canonical; the other three women, who appear in texts written by Jews prior to the birth of Jesus but not contained in the Jewish Scriptures, show the importance for Jews of women’s prayers.

Hannah

When Elkanah, husband of both Hannah and Peninah, offered annual sacrifices at the sanctuary in Shiloh, he gave single portions of meat to Peninah and her children, but he gave a double portion to Hannah, “because he loved her, though the Lord had closed her womb” (1 Samuel 1.5). The text asserts that infertility has nothing to do with sin or worth.

Deeply distressed over her inability to bear a child, Hannah “prayed to the Lord” (1 Samuel 1.10) in the Bible’s first explicit reference to a woman praying. Her prayer is a vow: were God to grant her a son, she would dedicate him to serve God as a Nazirite. The priest at Shiloh, Eli, seeing Hannah’s mouth move but hearing no words, presumes she is drunk and castigates her. Hannah explains, “I have been pouring out my soul to the Lord” (1 Samuel 1.15). Hannah inspired the Jewish tradition that, in silent prayer, we move our lips. The practice insures that we do not rush our prayers, that we think about every word, and that we pray with both our minds and our bodies.

Hannah conceives, bears a son, names him Samuel, and three years later, having weaned him, presents him to Eli. This action provides the model for the Feast of the Presentation of Mary in the Temple. Then, anticipating Mary’s Magnificat, “Hannah prayed and said, ‘My heart exults in the Lord… [who] raises up the poor from the dust…he will give strength to his king, and exalt the power of his anointed’” (2 Samuel 2.1-10).

Esther

The Hebrew version of the book of Esther, canonical for Jews, mentions neither prayer nor even God. The Greek Additions, written by Jews prior to the time of Jesus and contained in the Roman Catholic canon, depict both Esther and her guardian Mordecai at prayer. The setting of the story is ancient Persia, where the frequently inebriated king allows his prime minister Haman to order the genocide of the Jews. The queen, Esther, who has hidden her Jewish identity, “prayed to the Lord God of Israel and said: ‘O my Lord, you alone are our king; help me, who am alone and have no helper but you, for my danger is in my hand… O God, whose might is over all, hear the voice of the despairing and save us from the hands of evildoers. And save me from my fear!’” (Addition C).

Through a combination of courage and conniving, Esther saves her people. Not only does she prevail, she and Mordecai issue edicts proclaiming that Jews throughout Persia should keep the two days when the thwarted genocide had been planned “as days of feasting and gladness, days for sending gifts of food to one another and presents to the poor” (Esther 9.22). The holiday, known as “Purim” (named for the “lots” that Haman had cast to determine the dates for the Jews’ destruction), is celebrated by Jews to this day.

Judith

Likely dating to the first century BCE, the book of Judith is an obviously fictional text designed to instruct, encourage, and entertain its Jewish readers. The heroine combines the bravery and skill of Judith’s ancestor Simeon, the judge Deborah, Jael the Kenite of whom Deborah sings (Judges 4-5), and Judas Maccabaeus, who defeated the Syrian-Greek king Antiochus IV Epiphanes and rededicated the Jerusalem Temple that the king had defiled,

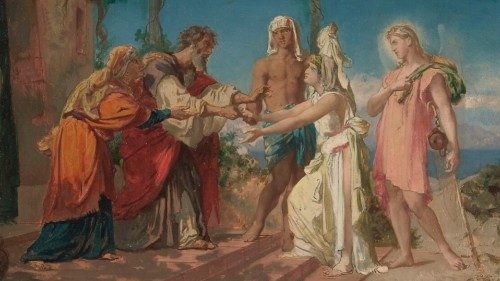

Judith is a beautiful, pious, and wealthy widow who, when the enemy general Holofernes threatens her town and the elders seek to capitulate, first prays and then acts. Her prayer, encompassing all of chapter 9, begins: “At the very time when the evening incense was being offered in the house of God in Jerusalem, Judith cried out to the Lord… ‘Give to me, a widow, the strong hand to do what I plan… Make my deceitful words bring wound and bruise on those who have planned cruel things against your covenant, and against your sacred house, and against Mount Zion….’”

Confident in that her prayer will be answered, Judith leaves her town and enters the enemy camp. Lying to Holofernes of her admiration for him, she encourages him to drink and when he passes out, she beheads him with his own sword. The narrative repeats that victory was gained “by the hand of a female” (8.33; 9.9-10; 12.4; 13.4, 14-15; 15.10; 16.5). Judith leads her people in a victory parade to Jerusalem, offers a Thanksgiving Hymn (encompassing all of 15.14-16.17), and returns to her house. The enemy soldiers, speaking of the Jews, correctly ask, “Who can despise these people, who have women like this among them?” (Judith 10.19).

Sarah

The Book of Tobit, a fictional comedy set during the Assyrian exile of the Northern Kingdom of Israel (722 BCE) but likely written in the early 2d century BCE, features a titular hero who displays saintliness by burying unattended corpses (until blinded by a bird defecating into his eyes), an angel in disguise, a magical fish, and a demon who had killed the seven husbands of the beautiful Sarah. Despondent over the deaths of the men she would marry, fearing herself a disappointment to her parents, humiliated by the taunts of the enslaved women in her household, Sarah “with hands outstretched… prayed and said, ‘Blessed are you, merciful God…. I turn my face to you and raise my eyes toward you. Command that I be released from the earth…. Why should I still live? But if it is not pleasing to you, O Lord, to take my life, hear me in my disgrace” (Tobit 3.11-15). Through the machinations of the angel Raphael, Sarah weds Tobit’s son Tobias. On their wedding night, Tobias exhorts his bride, “Get up, let us pray and implore our Lord that he grant us mercy and safety” (Tobit 8.4). Raphael explains that when the two prayed, he read the record of the prayer “before the glory of the Lord” (Tobit 12.12). The demon is exorcised, the marriage is consummated, and everyone lives happily ever after.

These four biblical women provide paradigms of prayer: for personal and political reasons, for healing and for strength, in despair and desperation, in fear and in confidence. They recognize what they need, express their concerns forthrightly to God, and follow their prayers with action. They and their prayers are models not just for other women, but for anyone who would speak to God.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti