As young Scouts in the Detroit area of the 1960s, we memorized the virtues that should shape our life. We all like bravery. Every issue of our monthly scouting magazine, Boys’ Life, carried at least one hair-raising true story of courage in the face of imminent peril. A young man pulling a family from a burning car. A teenager belly crawling across thin ice to rescue a child in frigid waters. We imagined ourselves in the picture, leaping to the heroic. Courage is popular.

The virtue called trustworthiness is not as big a hit. Trustworthy is tougher to visualize. We know we should not lie or steal. But it is hard to picture a negative. Our young minds tend to skew trustworthiness towards loyalty, especially to our country. The fifties and sixties were Cold War years. Our culture was immersed in spy drama: books, television, movies — as well as the real ones in the news. It was not hard to imagine trustworthiness as refusing cooperation with the enemy at all costs. That sounded exciting. Like bravery. Our Scout troop leader would not have it.

“It means doing what you said you are going to do,” Mr. Pelligrino harped on a trustworthiness that sounded dull and boring to us in the evening troop meetings at St. Michael Catholic School gym. “It means being where you should be when you are supposed to be there. It means people can rely on you.” His emphasis would increase in proportion to our waning attention.

That was sixty-some years ago. But based on that description of the virtue, we may be living in an age that needs trustworthiness more than it needs bravery. I have seen enough “No Fear” bumper stickers on Florida roads to last me two lifetimes. I am ready to see bumper stickers and decals that say, “No Excuses.”

My brothers in faith who live in prison must feel that way, too. I know the guys living at Union Correctional Institution and Florida State Prison sure do. They have heard it all. Promises to write. But there are no letters. Promises to visit. But there are no call outs. Just promises … promises … promises. A pocket full of mumbles, as Simon and Garfunkel called them in their song The Boxer.

In prison, when someone does what he or she promises to do, it is not soon forgotten. That may be why for decades, one of the best-known and most respected people on the entire prison compound at Union Correctional, was a short elderly man from outside who walked with a cane. The inmates pegged him with the unlikely moniker, “Big John.”

Big Johni, together with Juliaii, his wife of over sixty years, always promised to come back. He always did.

Kairos is a Cursillo-type weekend retreat that has been adapted to the interdenominational prison environment with emphasis on Scripture and the power of the Holy Spirit. The weekend retreat is given by free-people from parishes and churches near the prison. Inmates apply to participate in the weekend and are screened for faith readiness. The program is nationwide. It started at Union Correctional in Florida in the 1970s.

Big John showed up for the sixth Kairos weekend at Union Correctional in 1980. He attended close to 50 of the weekends only missing three over twenty years. Moreover, he and his wife Julia were regulars at the Sunday Catholic services at the chapels for Florida State Prison and Union Correctional for over two decades. Everyone knew that if the Big Man missed a Sunday Catholic service at the prisons, there was a big reason.

At his age, it was not hard to come up with a true excuse for not being able to attend the Mass or Communion service with our Catholic brothers in blue every Sunday. Big John was a man with no excuses. Big John just showed up.

John’s dedication and trustworthiness had a deep impact on me. As his slight frame eased into the prison grounds each week, cane in one hand and the other hand outstretched to greet everyone in his path, virtually every officer, every inmate, every guest knew that the shadow of a really Big Man had crossed their path.

There are at least seven levels of security which can be assigned to each of the almost 200 camps and institutions in the State of Florida prison system. Florida State Prison and Union Correctional, located right next to each other on opposite sides of a creek called New River, are assigned the highest level of security.

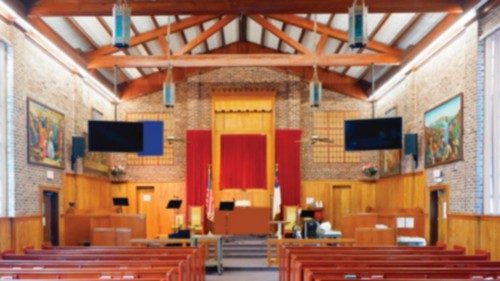

Starting with August 1998, my normal weekend schedule had me at the Saturday evening vigil Mass at our parish, St. Mary’s of Macclenny, where my wife Susan led the choir on her guitar. Then on Sunday morning I retrieved the Blessed Sacrament from the church before the 10:00 a.m. Mass and drove to the chapel at Union Correctional for the Sunday service there. Around 1:00 p.m. I headed next door to check in at the chapel at Florida State Prison. The Catholic service at Florida State Prison starts right after inmate lunch.

Only a handful of inmates are able to attend the chapel service at Florida State Prison. For all the rest in this prison, the service in the chapel is broadcast to their cells by closed circuit television. Catholic Communion must be brought to each one at his cell and provided through the food flap in the door to the man inside. We also use that moment to provide religious materials like statements from the Pope or the U.S. Bishops.

By the time the chapel Mass concludes, my handcart parked in the rear of the chapel was loaded-down with Catholic materials for distribution.

The chapel and Q-Wing are at opposite ends of the main corridor. From the chapel door to the Q-Wing door and back is a quarter mile. All the Catholic religious magazines and tracts that will be distributed at cell-front are on the cart. As I wheel the Catholic cart into the corridor and turn to the right, a hall officer motions for me to stop. He checks the contents of the cart and offers to oil the wheel that is squeaking.

Loudly discordant. Like mismatched cymbals clashing. That is the feeling that goes with passing out tracts of the Jubilee message of Pope St. John Paul ii to prisoners on Q-Wing in the late summer heat that day.

I thank the helpful officer while noticing that the door to Q-Wing seems awfully far away. After a few minutes, I am able to resume my trek from the Chapel of Light to the darkest wing in Florida’s prison system. Q-Wing houses maximum sensory deprivation, the death house and the execution chamber.

Q-Wing used to be called X-Wing. The name was changed in 1999. And one of the cells was sealed-off. The red security tape went up on the cell door and that door remained sealed for a very long time. I used to stop to offer Communion to the man in that cell. His name was Frank Valdez.

Frank was found in his cell one morning suffering from life-threatening injuries. He died from those injuries later that day. An official investigation followed. The results were as bad as everyone feared.

In July 2000 the Holy Father St. John Paul ii declared a year of Jubilee for prisoners. It was also the one-year anniversary of Frank’s death. I worked my way from cell-to-cell towing my cart and offering our Pope’s powerful words of encouragement and hope to the men on the most severely restricted wing in the state’s prison system.

Our Holy Father had said the Jubilee includes men in prison, even in the worst parts of a prison:

The Jubilee reminds us that time belongs to God. Even time in prison does not escape God’s dominion. Public authorities … are not masters of the prisoners’ time. In the same way, those who are in detention must not live as if their time in prison had been taken from them completely: even time in prison is God’s time.

The essence of prison is time. Doing time. The Jubilee is about redeeming time. Pope St. John Paul ii weaved this common fiber into a redemptive cloth.

At times prison life runs the risk of depersonalizing individuals, because it deprives them of so many opportunities for self-expression. But they must remember that before God this is not so. The Jubilee is time for the person, when each one is himself before God, in his image and likeness. And each one is called to move more quickly towards salvation and to advance in the gradual discovery of the truth about himself.

This was happening in Frank. Perhaps I could see it better than he because of my privileged vantage point. Holding a man’s hands in prayer. Placing the Eucharist on his tongue. Seeing a man as he is in the presence of his Creator.

I am told that Francis of Assisi genuflected in front of a notorious criminal, saying, “I kneel before the presence of God in you.” The man was transformed.

What man would not be changed to his core — no matter how terrible his mistakes — if he could see the presence of God in himself? How will he ever see this Presence in himself if we who claim to believe it do not see it first?

I believe Frank was starting to see it, beginning to see himself through the eyes of his Father in heaven. The last time I was with him, I sensed a new awareness in him of the value of his life before God.

We prayed. He received the Eucharist. I left on vacation. When I returned, he was dead.

It is usually hot on Q-Wing. In July, it is beyond hot. The poor officers who must endure hellish heat for hours at a time politely escort me through the wing. I greet the inmates who are sweltering in their cells.

Yet, even in the heat and the sweat, I find myself remembering Frank and the words of the Vicar of Christ:

[T]o celebrate the Jubilee means to strive to find new paths of redemption in every personal and social situation, even if the situation seems desperate. This is even more obvious with regard to prison life: not to promote the interests of prisoners would be to make imprisonment a mere act of vengeance on the part of society, provoking only hatred in the prisoners themselves.

i John Ekro Rapier, Jr. , passed away at 94 years old on April 5, 2003.

ii Julia M. Rapier, passed away at 94 years old on February 24, 2011.

By Dale S. Recinella

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti