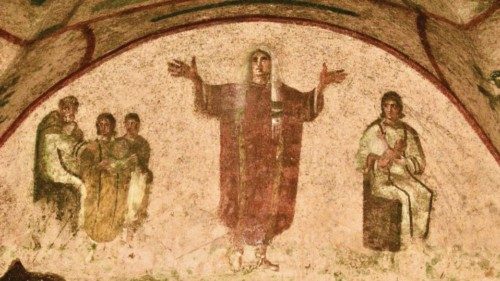

Religious life, both contemplative and active, as we know it today, has evolved over two thousand years. In this first of four essays, Christine Schenk summarizes what the literary record tells us about women in ancient Christianity.

When I was a young Sister of St. Joseph, I had a great desire to learn about our foremothers in the faith. While I dearly love the biblical texts, it is sometimes difficult to see myself in them because our lectionary texts nearly always feature our forefathers. Jesus’ dedicated women disciples — with the exception of Mary of Nazareth — are pretty much invisible. As I began studying for a master’s in theology at our local seminary, I devoured information about early Christian women. In this series of four essays, I hope to trace historical roots of women’s religious communities and perhaps help readers begin to recognize themselves in our early Christian history.

The Jesus movement spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire due in part to the initiative of female apostles, prophets, evangelists, missionaries, heads of house churches and widows. Its growth can also be attributed to the financial support from Christian businesswomen such as Mary of Magdala and Joanna (cf. Lk 8:1-3), Lydia (cf. Acts 16:11-40), Phoebe (cf. Rom 16:1-2), Olympias, a fourth-century deacon, and others. Pope Benedict xvi acknowledged as much on February 14, 2007, when he said, “without the generous contribution of many women, the history of Christianity would have developed very differently”. The “female presence in the sphere of the primitive Church”, he also noted, was in no way “secondary”.

Early house churches were led by women such as Grapte, a second-century leader of communities of widows who cared for orphans in Rome and Tabitha, a first-century widow “devoted to good works and acts of charity” (cf. Acts 9:36-43), who founded a house church community in Joppa. Through the house church, early Christians gained access to social networks that brought them into contact with people from diverse social classes.

When a female head of household, perhaps a wealthy widow such as Tabitha, or a freed woman, such as Prisca (cf. Rom 16:3-5), converted to Christianity, Christian evangelists such as Junia (cf. Rom 16:7) or Paul gained access not only to her domestic household but also to her patronage network. This meant that her slaves, freed persons, children, relatives, and patronal clients would convert as well. Thus, when Paul converted Lydia (cf. Acts 16:11-15), he automatically gained entry to a broad swath of social relationships, and a potentially wide audience. In their exhaustively researched book “A Woman’s Place”, Carolyn Osiek and Margaret Y. MacDonald demonstrate that lower-class Christian women could begin businesses within their Christian social networks, and become financially secure. This brought with it higher status and freedom of movement, especially throughout the extended household of antiquity.

Celsus, a notorious critic of the early church, held a dim view of female evangelization. Yet, he unwittingly supplied outside evidence of women’s initiative in early Christianity when he said Christians convinced people not to “leave their father and their instructors, and go with the women and their playfellows to the women’s apartments, or to the leather shop, or to the fuller’s shop (Origen, “Against Celsus”).

Celsus’ critique coincides with evidence from other early Christian texts that evangelization was conducted person-to-person, house-to-house, by women who reached out to other women, children, freed-persons, and slaves. His criticism tells us that Christian women (and a few good men) took initiative outside of patriarchal norms because of their belief in Jesus.

There are three significant differences between 1st- and 4th-century Roman society that can be attributed to the evangelization and leadership ministries of Christian women. First, by the 4th century, the freedom to choose a life of celibacy effectively dismantled one pillar of patriarchy — mandatory marriage. Second, Christian widows and virgins rescued, socialized, baptized, and educated thousands of orphans who would otherwise have died of exposure or would have been doomed to prostitution. Third, the domestic networking and evangelization activities of women played a leading role in transforming Roman society from a predominantly pagan to a predominantly Christian culture.

Elements of religious life can be recognized not only in the early communities of widows such as Grapte and Tabitha, but also in the women who chose a life of celibacy, such as Phillip’s four prophetic daughters (cf. Acts 21:9) and the female communities in Asia Minor represented in the Acts of Thecla. Women in these communities not only rescued orphans and poor widows, but also prophesied in the earliest Christian gatherings (cf. 1 Cor 11, Acts 21:8-10). Their countercultural exercise of authority in the context of everyday domestic life is one oft-unheralded key to Christianity’s rapid expansion. The missionary authority and prophetic leadership of women within their extended social networks changed the face of the Roman Empire.

#sistersproject

By Christine Schenk csj

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti