As he continued his series of catecheses on vices and virtues at the General Audience on Wednesday morning, 24 January, Pope Francis warned the faithful about the danger of greed. It is a sickness of the heart and a distortion of reality that hinders us from being generous, he stressed. The following is a translation of the Holy Father’s words, which he shared in Italian in the Paul vi Hall.

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Good morning!

We are continuing our catechesis on vices and virtues, and today we will talk about greed, that form of attachment to money that keeps man from generosity.

It is not a sin that regards only people with large assets, but rather a transversal vice, which often has nothing to do with bank balances. It is a sickness of the heart, not of the wallet. The Desert Fathers’ analysis of this evil showed that greed could even take hold of monks, who, after renouncing enormous inheritances, clung to objects of little value in the solitude of their cells: they would not lend them, they would not share them and they were even less willing to give them away. An attachment to little things, which takes away freedom. Those objects became a sort of fetish for them from which they could not detach themselves. A sort of regression to the state of children, who clutch their toy repeating, “It’s mine! It’s mine!”. A distorted relationship with reality lurks within this claim, which can result in forms of compulsive hoarding and pathological accumulation.

To heal from this sickness, the monks proposed a drastic, though highly effective method: meditation on death. As much as one can accumulate goods in this world, we can be absolutely sure of one thing: they will not enter the coffin with us. We cannot take property with us! Here, the senselessness of this vice is revealed. The bond of possession we create with objects is only apparent, because we are not the masters of the world: this earth that we love is in truth not ours, and we move about it like strangers and pilgrims (cf. Lev 25:23).

These simple considerations allow us to see the folly of greed, but also its innermost raison d’être. It is an attempt to exorcise fear of death: it seeks securities that, in reality, crumble the very moment we hold them in our hand. Remember the parable of the foolish man, whose land had offered him a very abundant harvest, and so he lulled himself with thoughts of how to enlarge his storehouse to accommodate all the harvest. The man had calculated everything. He had planned for the future. He had not, however, considered the most certain variable in life: death. “Fool!” says the Gospel. “This night your soul is required of you; and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?” (Lk 12:20).

In other cases, it is thieves who provide this service to us. Even in the Gospel they make a good number of appearances and, although their work may be reprehensible, it can become a salutary admonition. Thus preaches Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount: “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal” (Mt 6:19-20). The same accounts of the Desert Fathers tell the story of a thief who surprises a monk in his sleep and steals the few possessions he had in his cell. When he wakes up, not at all disturbed by what had happened, the monk sets out on the thief’s trail and, when he finds him, instead of claiming the stolen goods, he hands over the few things that remained, saying: “You forgot to take these!”.

We, brothers and sisters, may be the masters of the goods we possess, but often the opposite happens: they eventually take possession of us. Some rich men are no longer free, they no longer even have the time to rest, they have to look over their shoulder because the accumulation of goods also demands their safekeeping. They are always anxious, because a patrimony is built with a great deal of sweat, but can disappear in a moment. They forget the Gospel preaching, which does not claim that riches in themselves are a sin, but they are certainly a liability. God is not poor: he is the Lord of everything, but, as Saint Paul writes, “Though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor 8:9).

This is what the miser does not understand. He could have been a source of blessing to many, but instead he slipped into the blind alley of misery. And the life of a miser is ugly. I remember the case of a man I had met in the other diocese, a very rich man, and his mother was sick. He was married. The brothers took turns caring for the mother, and the mother used to have a yoghurt in the morning. This man would give her half in the morning and the other half in the afternoon, to save half the yoghurt. This is greed, this is attachment to things. Then this man died, and the comments of the people who went to the vigil were: “But you can see that this man has nothing on him; he left everything”. And then, making a bit of a mockery, they would say: “No, no, they couldn’t close the coffin because he wanted to take everything with him”. This greed makes the others laugh: the fact that in the end, we must give our body and soul to the Lord and leave everything. Let us be careful! And let us be generous, generous with everyone and generous with those who need us most. Thank you.

Special Greetings

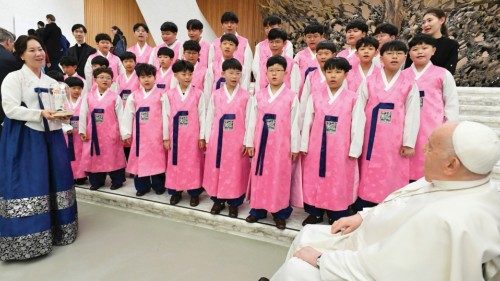

I extend a warm welcome to the English-speaking pilgrims and visitors taking part in today’s Audience, especially the groups from Scotland, Korea and the United States of America. Upon all of you, and upon your families, I invoke the joy and peace of our Lord Jesus Christ. God bless you!

This Saturday, 27 January, is International Day of Commemoration in memory of victims of the Holocaust. May the remembrance and condemnation of that horrible extermination of millions of Jewish people and those of other faiths that took place in the first half of last century, help us all not to forget that the logic of hatred and violence can never be justified, because they negate our very humanity.

War itself is a negation of humanity. Let us not tire of praying for peace, for an end to conflicts, for a halt to weapons and for relief for stricken populations. I am thinking of the Middle East, of Palestine, of Israel, I am thinking of the disturbing news from tormented Ukraine, especially the bombings that hit places frequented by civilians, sowing death, destruction and suffering. I pray for the victims and their loved ones, and I implore everyone, especially those with political responsibility, to protect human life by putting an end to wars. Let us not forget: war is always a defeat, always. The only ones to “win” — in inverted commas — are the arms manufacturers.

Lastly, my thoughts turn to young people, to the sick, to the elderly and to newlyweds. Today, we celebrate the liturgical memory of Saint Francis de Sales, a teacher of spiritual life. He taught that Christian perfection is accessible to everyone, whatever their state of life or their social condition may be. May you too live the situations in which you find yourselves as paths to holiness to be journeyed on with confidence in God’s love.

I offer my blessing to all of you!

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti