StoryoftheMonth

Dhuoda was born a few years after Charlemagne's coronation as emperor, presumably around 803. What is certain is that in 824 she married the very powerful Bernard of Septimania, who was a relative of the sovereign. The setting is the south of what is today's France, in that Occitania lying between the Provençal slopes of the Alps and the lower climbs of the Pyrenees. In fact, Dhuoda provides us with the spatial and chronological coordinates. In 826, William, the first son, was born. A few years later, he followed his father on military campaigns in the retinue of the new emperor, Louis the Pious. The father’s death in 840 made the situation complex. Conflicts arose between the heirs, and Bernard, Dhuoda's husband, bet on the wrong horse. Defeated, he had to give up his son William as a hostage. Nevertheless, this was not enough. The same fate befell his second son, born in March 841 and snatched, as an infant, from his mother’s loving care.

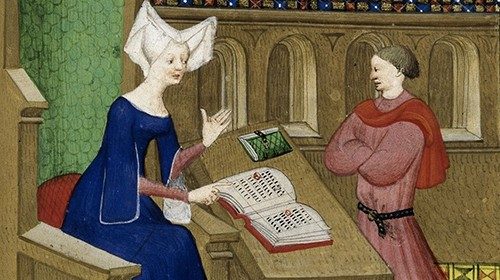

This is the context of Dhuoda’s Liber Manualis, which is a kind of treatise on education, written between November 841 and February 843. In the book Dhuoda. Figlio mio, indirizzo a te questo scritto [Dhuoda. My son, I address this writing to you] (Ed. San Paolo), Maria Antonietta Grillo recounts the emptiness and, most likely, the desperation of a mother who driven by the desire to be useful turned to her son. She wrote, “I am sending you this booklet so that you can read it as a mirror of your education; I will be happy if my absence can be made up for by the presence of this little book of mine, when it is sent to you by my hand, I want you to hold it in your hand with love”. Dhuoda asked William to pass on those same pages, and his teachings, to her second son, whose name she did not even know. “When your brother, so small, has received the grace of baptism ... do not be sorry to initiate him, educate him, love him, incite him to ever better work”.

The text includes religious moral teachings, which are addressed to the son whom the author knew she could not educate personally. By establishing a long-distance bond with him, the mother transmitted the sense of love towards God, and of a faith to be nourished daily, with prayer and charity.

Mother, writer, pedagogist (though not in the sense of a Montessori ante litteram), Dhuoda talked a lot about herself. The Liber Manualis is, in fact, the autobiography of a woman who, despite her relative loneliness, remained one of the most powerful women in France. She lived in Uzès, in the Midi, and was extraordinarily well educated, including –but not only-a thorough knowledge of the Holy Scriptures. In its foundation, she had a classical culture that made her perfectly aware of what auctoritas was, that is, the authority attributed to the great writers of the past. In a Latin that is certainly far from classical but nonetheless effective, Dhuoda refers to Pliny the Elder and Ovid, St Ambrose and St Augustine.

Dhuoda’s story does not have a happy ending. The constant state of war and the insecurity of the latifundia did not allow her to collect the rents from the land, so she was forced to take on huge debts. Meanwhile, her husband and son were accused of treason, which led to them being executed in 844. However, Bernard, the child that his mother could not even wean, had a better fate. After many years, he acquired significant titles and lands, including those that Aquitaine had left to William the Pious, grandson of Dhuoda and founder of the famous Benedictine abbey of Cluny (909). (Giuseppe Perta)

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti