This month’s issue of Women Church World reports on female artists and their relationship with the sacred. This journey commences with those who had been famous and sought after in their time, then long forgotten, only to return to the limelight in the 20th century. These talented and skillful women occupy a notable place in art history. Today, their art is held in museums and private collections, and sought after by collectors who pay significant sums to possess a piece. These artists often learned their technique in their father’s workshops, or were self-taught in convents, some at a very young age. An example of such an artist is the prolific Elisabetta Sirani, a star of the Bolognese Baroque, who was considered by her contemporaries to be “the best paintbrush in Bologna”. In her short life - died at the age of 27- she managed to paint two hundred works, ninety of which were completed before she was seventeen.

The making of art for women was [and is] not only an opportunity to pursue a career, but also a way to emancipation. For example, Lavinia Fontana made her future husband agree to a “marriage contract” that was quite unusual for those times. In the document, it was stated she would continue her career as a painter while he would essentially act as her agent. In a special way these artists were ahead of their time; they were pioneers in their tackling of themes about the female world by depicting strong, determined, independent characters, while challenging the respectability of the time. In their works, we find art, suffering and passion. LIFE. Artemisia Gentileschi denounced the violence she had suffered at a time when it seemed impossible to do so, and faced trial for doing so, even though she was forced to endure a long series of questioning and interrogation under torture.

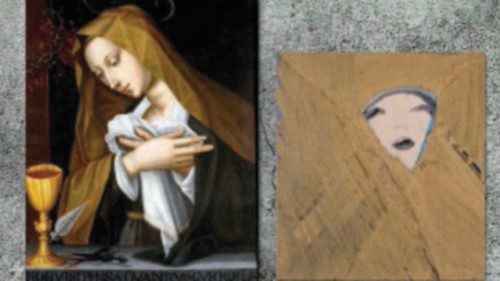

These painters approach to the sacred is visible in their choice of subjects they depicted. For example, there are saints who were famous for their martyrdom, be that biblical characters or evangelical scenes. However, more than anything else, the common thread is the narrative of Good and Evil, life, death, guilt, punishment, conversion, and redemption. In this context, Barbara Jatta, the director of the Vatican Museums, comments on certain works by female artists who have depicted the women from Jesus’ life, “A visual testimony of harmony that also by virtue of the intimate nature of its realisation manages to strike the heart even deeper, and warm it up”.

Contemporary art critic and curator Gianluca Marziani, on the other hand, dwells on the marriage between women artists and the sacred in the 20th century. This was a century that “overturned the canonical models of figuration, opening the work to the sphere of dream and the surreal, to abstractions and avant-garde experiments”.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti