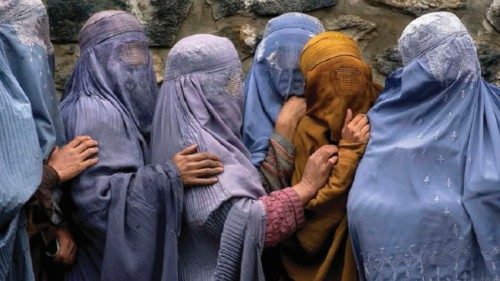

They gradually disappear over the horizon, almost as if they were pictures that have faded over time. They are the women in Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 has created a real wave of restrictions against women. To date, at least 80 edicts have been issued to limit their freedom and rights. Women are barred from attending high school, joining the work force and leaving the house alone. They cannot use public transportation, enter city parks or wear makeup or heels. Theirs is an extremely restricted, even claustrophobic, life, a nightmare of sorts, especially for those who live in rural areas — in other words, the majority of the Afghan territory.

Last May, Amnesty International and the International Commission of Jurists published a report titled, “The Taliban’s War On Women: The crime against humanity of gender persecution in Afghanistan”. In the document, the organizations call for the investigation of “all alleged crimes amounting to crimes under international law and other serious human rights violations in Afghanistan, including against women and girls”, which “may amount to the crime against humanity of gender persecution” (p. 52, 2). They also suggest that States “should promote and support the exercise of universal or other extraterritorial jurisdiction at the national level with the aim of investigating and prosecuting crimes under international law committed by the Taliban” (p. 3).

In fact the current situation is tragic: “Women are slowly disappearing from society; they are like fading pictures”, Simona Lanzoni explains to L’Osservatore Romano. She is the Vice-president of the Pangea Foundation which since 2002 has been working to promote women’s economic and social development. “That’s why we ask that every government which calls itself democratic not recognize the Taliban, until women are allowed to participate in public life. If all of this is passed off as normal, then it sends a dangerous message for everyone. The fight for Afghan women’s rights is essentially a fight that affects the rights of all women around the world”.

Another cause for concern is the children: “The country is on the brink of starvation”, Lanzoni continues, “and mortality rates of women and newborns at the moment of birth have increased, also because when a mother dies, her child has an extremely low chance of survival. A denied childhood”. Huma Saeed, a human rights researcher born in Afghanistan, echoes the vice-president of Pangea. “The serious humanitarian crisis the country is experiencing has a heavy impact on children. Due to the high poverty rate, many of them are forced to work from an early age to help support their family, or they are sold so their parents can earn some money”. The trafficking of minors, explains Saeed, primarily entails “forced marriages of 12- or 13-year-old girls, but we can hypothesize that it also involves organ trafficking, even if it is more difficult to obtain accurate data on this”.

The researcher’s appeal then, is that the world not turn a blind eye: “Although it is a complex historical moment on the global level, with so many ongoing conflicts, Afghanistan must not be forgotten”, says Saeed. “Above all, the international community must reject the Taliban government, because it carries out gender discrimination and violates the fundamental rights of women and children (in other words, more than half of the Afghan population), and this is a crime”. Lastly, “a way to adequately sustain the population must be found, so that external aid reaches them, with certainty and so that it does not end up instead in the vortex of corruption”.

For now, the lives of Afghan women are at risk every day, even when it comes to “small daily tasks”, highlights Graziella Mascheroni, President of cisda , (Coordinamento italiano sostegno donne afghane), and this includes “a dizzying increase in mental disorders, depression and suicides”. This is why, in collaboration with rawa (Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan), which was founded in the 1970s and is highly active in the sociopolitical sphere, cisda supports various projects for women’s empowerment: “We try to boost their education”, Mascheroni continues. “We support a mobile medical unit to reach the most distant villages, where women do not have health care; we sustain small craftsmanship, such as sewing classes, to allow young women to contribute to supporting their families”.

Among the many projects cisda supports, there is one of which the president speaks with particular enthusiasm. It is called “Giallo fiducia”, and it includes saffron cultivation in the province of Herat and a literacy course for women. Mascheroni speaks about this programme with satisfaction, because it is like a light amid the many shadows that darken Afghanistan. It is a small light, but a light nonetheless. “The last time I was in Herat was in 2019”, she shares, “and I visited the very headquarters of this project, where I saw women who were truly enthusiastic to have a job and to be able to support their loved ones. One of them told me she wanted to be an entrepreneur. She wanted to ask her brother to use one of their family’s fields to cultivate saffron, also including other women. She wanted to help other women the way she had been helped. And this”, concluded Mascheroni, “seemed to me a very beautiful sign of hope for all women”.

Isabella Piro

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti