The question of how the beautiful experience and momentum of the First Session of the Synod on Synodality can be realized in local churches is both urgent and critical. A synod is more than a set of proposals, teaching, and inspiration on how to be a church. A synod is a way of life, a culture, and an ecclesial practice that renews and transforms the church. To accompany God’s people and reinvigorate the missionary life of the church and her members, following the successful first session of the Synod on Synodality, there is the need to samaritanize the synodal process at all levels of the church’s life. How this could be done is the main concern of this theological reflection.

The Synodal Synthesis report invites the people of God to enter deeper into the synodal process through local efforts aimed at “deepening the issues both pastorally and theologically, and to indicate their canonical implications.” All of God’s people are invited to participate on this journey. The inspiration and initiatives that the Spirit is birthing in the church emerge naturally from all the people of God in communion with pastoral leaders and the episcopal conferences. The synodal way should become the church’s way of life that implicates all of God’s people in hearing and heeding the Word of God by listening to one another. As the great African father, Bishop Cyprian of Carthage wrote (Ep. 34. 4. 1), “I do not think that I should give my opinion in isolation. I must know details of these cases and study the solution carefully, not only with my colleagues, but with all the people. It is important to think about everything and weigh it carefully before making a ruling which will constitute a precedent for the future.”

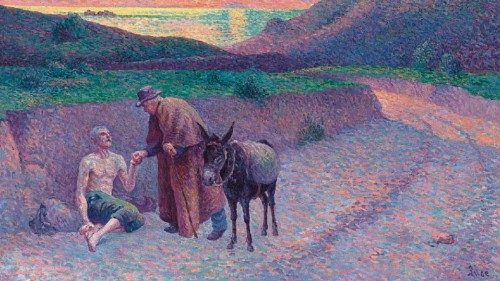

The most challenging reality that confronts the church today as always is how to enter the stories of the ‘joys and hopes’ of today’s world, and the wounds and brokenness of men and women today which have been expressed in many and varied ways since 2021 when this synodal journey began. As Pope Francis puts it in his address to the delegates, “communion and mission can risk remaining somewhat abstract, unless we cultivate an ecclesial praxis that expresses the concreteness of synodality ... encouraging real involvement on the part of each and all” (October 9, 2021). The central ecclesiological dynamics of Pope Francis’s magisterium is the communicative act that happens in the space of encounter when we experience the Samaritan way when confronted with the suffering and pain of the other. In such an encounter, we see clearly, we diagnose and judge the situation properly, and we respond justly and prophetically with the balm of compassion, love, and action. The proper response is a reversal process that changes the painful situation and brings a new birth of hope and a new life.

Seeing, recognizing, interpreting, and responding in an adequate and prophetic manner unify our Christian witnessing with the priorities and practices of Jesus and births a new experience of the resurrection and hope for those who suffer and are abandoned in the existential peripheries of life. The mission of Christians and churches is as Mons. Lucio Ruiz writes in reference to Pope Francis’s ecclesiology, the “samaritanization of culture.” It is only by adequately responding like the Good Samaritan to others in a loving and compassionate way and doing something about the sad and painful condition of others that we can truly create a community where everyone cares for everyone and where we see in each person what God sees in them — a child of God. In this way, the church not only proclaims the Word of God through words, but also through credible deeds, showing and witnessing to the world the power and presence of the liberating, teaching, saving, and healing mission of God’s Son by bending down to those who are fallen and forgotten.

Pope Francis’s ecclesiology invites us to begin with the question: Where is the Church, not who is the Church? In the biblical tradition, the question, “Where are you?” is always posed to either bring believers to their senses or point them towards God when they forget the way to God. The question also locates a person and community properly within the direction of God’s call. After the Fall, the question God asked our first parents was not “Who are you?” but “Where are you?” (Genesis 3:9). After Cain killed his brother Abel, God asked him, “Where is your brother, Abel?” (Genesis 4:9). If we examine the theophanies in the OT in the call of Abraham, Moses, Elijah, and many others, the place of meeting was not only significant, but also decisive. In the case of Moses in Exodus 3, God says to him, “take off your shoes for where you are standing on is holy ground” (v. 5). The synodal process invites us to move towards others so that we can stand with them where they are searching for God as they advance towards the Promised Land of hope and love.

This next phase of the synodal process is an invitation to journey together with everyone and meet them where they are in a spirit of love and acceptance. As a result, the synodal gathering space must be characterized by what Hans urs von Balthasar calls the crystallization of love. The current synod uses the image of ‘a tent’ to capture the image of the new ecclesiology of decentering of the center, and centering the mission of the church around the sites of the pain-filled world today where many people are wandering without direction, desiring to be wrapped in the cloak of love and friendship. There will always be resistance to this ecclesiology from those who benefit from existing power relationships when they perceive a threat to their power from those who like Jesus desire to upturn the moneychangers’ tables. However, we are witnessing a huge cultural shift which is creating ruptures in our world of meaning and how we perceive power.

In his work, The End of Power, Moisés Naím argues with regard to religious organizations that the so-called sheep are no longer sheep anymore because they are now consumers who are beginning to embrace and reject religious systems and narratives because of the bazaar of options available to them. Religious loyalty and affinity are weakening because adherents could easily find other “more attractive products in the market for salvation.” This reality, while it will not topple the strong spiritual authority and influence of the Catholic Church, for example, will however “narrow the range of possibilities and reduce the power” of the church in many parts of the world — both in the Global North and in the Global South. The synodal process is, therefore, helping us to begin to reimagine the use of power in the church and how to use the gifts and talents of all peoples and all cultures beyond the selfsame structures and systems that have served the church to this moment. Theologically, what the social scientists are saying is akin to what we call conversion. Admitting that the existing hierarchies of power, interests, and domination harm the missionary work of the church is an invitation to conversion, a turn towards God and our neighbors and away from our egos and idols — cultural, racial, ecclesial, political, and economic.

Ultimately, samaritanizing the synodal process invites the church and its members to a renewal of inter-subjectivity in the church that begins from within the hearts of all persons as an inner grace and interior logic of love. From this interior desire, arises a movement in which the human person seeks the connection with the other in what the African ancestors captured as ubuntu, that is the wisdom that says that the recognition of the other makes me human or rather that in affirming the humanity of the other, I affirm my own humanity. We Africans believe that a deeper encounter of this kind can be accomplished through a synodal process that embraces everyone as a family of God. In the context of the church-as-family, a space for a polylogue can emerge through the synodal process where everyone shares their stories, lamentations, hopes and dreams. In this empowering space, we intentionally include everyone, particularly those whose voices are muted or those who have been made invisible by injustice, discrimination, and social hierarchies. It is in such spaces that people can discern in the Spirit what God is saying through the experiences of everyone and together find our path to the future and the healing for our wearied souls in times like these.

* Fr Stan Chu Ilo is a Nigerian priest of Awgu Diocese, a research professor of ecclesiology, world Christianity and African Studies at the Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology, DePaul University, Chicago, U.S.A; and the Coordinating Servant of the Pan-African Catholic Theology and Pastoral Network.

Fr Stan Chu Ilo*

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti