We who were the other

Dear young friend,

I am pleased and rather struck by your request. You ask me about my experience at the Second Vatican Council. I will try to tell you what that opening meant for us. Whether lay or religious, each one among those who gathered on the Tribune of St Andrew’s in St Peter’s passed through her experience in the Church, an experience made in the most diverse places, from Egypt to Lebanon, from Europe to Latin America. We knew the Church; we knew, certainly, a part of her, each in a different way, from the street to the convents, to the institutions. Some of us had important roles, weaving worldwide networks among nuns or between laywomen and laymen, we all knew the conflicts and tried to get some idea of the needs. In the end, it may have been just a part, but it was a substantial part. And yes, we had been waiting.

When John XXIII announced the Council, we felt an energy spreading through our bodies and minds for having been gathered with all the hope for renewal, for interlocution between the Church and what was happening in the world. We listened. To illustrate how, I will give you an image, we rose up on tiptoe to see better. You know what those years were like, what ferment there was. It seemed that a new time was being prepared, which was more adequate to life. An attention to the poor, to nonviolence, and to women’s voices becoming more and more authoritative; even the Church was touched by that ferment.

When, in April 1963, John XXIII promulgated the encyclical Pacem in Terris, it really seemed to us that spring had arrived, as it does in our hills. Every word of that encyclical responded generously to our wishes, starting from the first word of the title, which was Peace. Nevertheless, what we perhaps did not expect was to see recognized among the signs of the times, along with the role of the working classes and the self-determination of peoples, the entry of women into public life. “Woman, in fact”, we read, “are gaining an increasing awareness of their natural dignity. Far from being content with a purely passive role or allowing themselves to be regarded as a kind of instrument, they are demanding both in domestic and in public life the rights and duties which belong to them as human persons”. It was all there already, there was only to unravel the thread, to go to the consequences that were necessary and obvious.

You tell me, however, not only during Session I, but also in Session II, where the Outlines for The People of God and the Laity, and The Vocation to Holiness in the Church were being discussed; issues that could not even be conceived without us, even then there were women. You remind me that even the communion of a female journalist created a situation, and she was prevented from taking it together with her male counterparts. Were we not struck, you ask, by this exclusion? Of course, I understand your dismay; it is only healthy and right.

It was during Session II, when laying his eyes on all the prelates present, did Belgian Cardinal Léon-Joseph Suenens stand up and ask, “But where is the other half of the human race here?”.

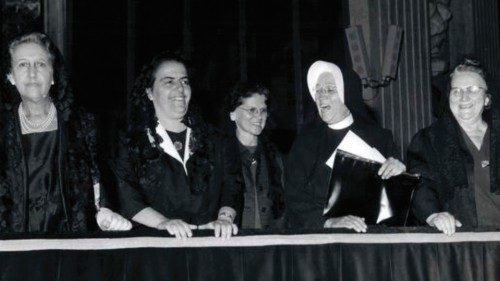

The other half of humankind, beginning with Section III of the Council, which opened in September 1964, to a minimal and seemingly silent degree, set foot at the Council. There were symbolic female presences, Paul VI had said. John XXIII had died on June 3, 1963. The female auditors arrived almost at a dime a dozen, and by the end of 1965, there were 23 laywomen and us religious.

You can imagine, it was exciting to have received the invitation letter, the daily routine was also exciting, we had a card signed by the Vatican Secretariat of State and we were going to take the steps of the Tribune of St Andrew. We were looking out over all of St Peter’s, and the prelates struck us, the marble sculptures that we knew well all of a sudden were full of life, we were looking out over the history of the Church at a time when there was such expectation. We were lay and religious together, there were ten religious, and we were in the male and female Tribune, auditors together. Before the outlines were discussed, an expert would come and explain them to us, and it was all teeming with different languages, and of interpreters.

True, as you remember, that we were not able to have our voices directly resonate there; there were interventions by some spokespersons of the auditors, but they were always men, and those times that a spokesperson was proposed, which was Spain’s Pilar Bellosillo of the World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations, her intervention was always rejected. However, you have to be clear, though, that there were many ways of intervening, of having the things we had to say considered. There are the documents we used to draft and deliver; there are the informal meetings, the corridors, the dinners in homes. Outside of St Peter’s we would meet at Santa Marta or at the Sisters of Holy Child Mary Institute on Via del Sant’Uffizio and the lay and religious women had a chance to get to know each other, we set up a Commission, we brought our perspectives close together

You were struck by the history of the bar, the prelates who in embarrassment and so unaccustomed to female presences had a small refreshment room prepared just for us while keeping us away from the premises where they met and talked informally with each other. The wittiest among us called it Bar Nun (nun’s bar, nobody’s bar), a small room covered in yellow velvet where tea and pastries were served. It did not make you laugh that the Mexican couple Luz Maria Longoria and José Alvarez Icaza, invited as a couple, were separated by the bizarre and seemingly improvised protocol. You mentioned segregation, and how can I blame you? I too was puzzled, there was unbelievable behavior, but perhaps I was puzzled for a slightly different reason: to think that we twenty-three, so few, yet also so attentive, respectful, and excited, were arriving like a storm that disrupted customs; to think that we were found by our mere presence so difficult to trace back to protocol order, struck me.

Once we arrived, that order was undone, our presence required new criteria, a renewal of everything. We laughed a lot in those months at those Alice in Wonderland absurdities. We laughed with bonhomie, almost with tenderness even at the resistance we encountered. Sister Costantina Baldinucci, the president of the Italian Federation of Religious Hospitallers wrote in her memoirs of the Council, “There were three categories: a minority of ‘good guys’ who truly appreciated our presence and respectfully offered their input. The majority behaved with indifference. Some appeared frightened and even avoided meeting us. Some, then, clearly disapproved of our being there and avoided us altogether”. And they did. Nevertheless, it was funny to see how they avoided us; they had the problem, not us.

It also makes you angry at our humor, you say it’s typical, women who mother men even older than themselves, even powerful men and feel better, look at them tenderly, laugh at them, and meanwhile everything remains as it is. I will think about it, you certainly have your reasons, but Luz Icaza’s trilling laughter still brings me joy.

Then there is more, my dear. We were Church; we carried in there perhaps more of the Church acting in the world than many prelates did. There was Marie-Louise Monnet, of the Mouvement International d’apostolat des Milieux Sociaux Indépendants; there was Mary Luke Tobin, president of the Conference of Major Superiors of Women’s Institutes of the United States; there was Marie de la Croix Khouzam, president of the Union of Religious Teachers of Egypt; there was Sabin de Valon, superior of the Ladies of the Sacred Heart; there was Rosemary Goldie, executive secretary of the Standing Committee of the International Congresses for the Apostolate of the Laity, to name but a few. We -the sign of the times that we were- took it seriously, so it seemed to us that the problem was not so much ours: we were making segregation visible while announcing its demise.

Our contribution came through documents given to the commissions. It is recognizable in many Sessions, and it is enshrined by Monsignor Angelo Dell’Acqua’s intervention in audience on January 21, 1965 with Sister Baldinucci. The position of auditor commits “to make a contribution of study and experience to the commissions charged with reviewing and amending the outlines of the IV Session”. And the contribution we gave is visible and not even so much hidden in the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes, not only in it’s lines when the dignity of women is mentioned.

However, you are not satisfied and you say that even before the Council, and not only among German theologians, they were talking about women’s diaconate, priesthood, on so many things the Council is great, but on women it is an elephant that has given birth to a mouse. Beloved friend, watch out for that little beast. Vatican Council II made it possible to open the theology faculties to women, the study and teaching of theology, and I know you’re thinking about it, maybe you too will be a theologian someday, and today, you know, women theologians are revitalizing biblical studies and changing perspectives on liturgy and everything about the Christian life. In addition, the fact that they have not made it to the priesthood yet, it seems like misfortune, but maybe it is a grace. Do you remember the final chorus of Adelchi, the chorus of Ermengarda? You endowed with a providential misfortune among the oppressed. The history of women in the Church has meant that, whether abbesses or saints, women found themselves on the other side from the clergy. With the laity. Since they were not and are not priests, the new space they create every day in the Church is a space for the apostolate of laymen and women, a space that grows. Meanwhile, they give a new breath to the Church, more osmotic, freer, and wider.

by CAROLA SUSANI

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti