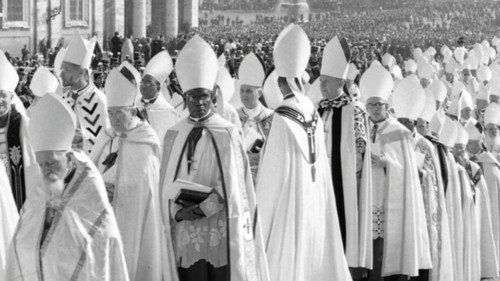

On October 11, 1962, I ran home to sit myself in front of the television set, where I remained for hours watching the very long procession of bishops entering the council hall. At that time, I certainly never thought that event, understood only up to a point certain point by a rebellious teenager, would profoundly affect my life and change the face of the Church. Nothing would ever be the same again and a new subject would make their appearance. I speak, of course, of women theologians and the theology they would elaborate, which in my opinion is the most innovative and relevant fact in the methodical-critical reflection on faith in the six decades since.

Although condemned to silence and invisibility, women had already measured themselves critically with faith. I recall Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz who had chosen to become a nun among the “Geronimites”, emulating the women of the Aventine, the students and collaborators of St Jerome. Her bold stand had reaffirmed for her -as for other women- the obligation of silence. At one's own peril, the only way out was prophetic loquacity and mystical experience, while being subjected to clerical male scrutiny. Hildegard of Bingen, Catherine of Siena, Bridget of Sweden, Domenica of Paradise, Teresa of Ávila, Maria Magdalena de’ Pazzi emerged victorious. There were others too who had paid with their lives - suffice it to recall Margaret Porete.

Nevertheless, women were developing a feminine theology, which flourished mainly in monastic contexts. In the transition to the modern age, they claimed access to Scripture, read by some in the original languages. On this track of learned acquisition of faith is the story of Elisabetta Cornaro Piscopio, the first woman to apply for a degree in theology. She was denied by what Apostle Paul had stated, keep women in the Church silent. However, she could not be held back from graduating in philosophy; her family was too important to oppose a radical refusal.

It took more than two centuries for women to be awarded degrees in the various disciplines, penultimate was medicine, while the very last of all was theology. Henceforth, it fell to me to be among the first in Italy to attend the faculty. This was in October 1968. Two years later Maria Luisa Rigato was admitted as an auditor to the Pontifical Biblical Institute while its rector was Carlo M. Martini. The following year there were several students who within two years would be among the students on all Roman ecclesiastical faculties.

Elsewhere this had happened earlier. I mention among the very first to earn that title the American Mary Daly and the German Elisabeth Moltmann Wendel. The latter recounted that they did not know how to refer to her on the diploma, so they chose the formula of “virgo sapientissima”!

In parallel, women were accessing professorships and completing fundamental research in history, patristics, and the Bible. To the German Elisabeth Gössmann, the thesis censor had to reproach a generational flaw: she was born too early and, in fact, never in her homeland would there be a professorship for her.

I landed in the Faculty of Theology with a degree in philosophy already in my pocket, and I conducted my studies for a four-year period, earning my licentiate. I was then asked to pursue a doctoral year, and for my thesis, I decided to study John Chrysostom’s conception of the feminine, having come across his epistolary to the female deacon Olympias. I had underestimated the volume of the writings on the subject, and the course turned out to be slow going. Added to this, in 1974/75, I had been offered to teach a course on the Introduction to Theology at the School of Theology for Laity in my diocese. The following year I taught ecclesiology too and immediately afterwards I was co-opted to the St John the Evangelist Theological Institute for Western Sicily. In short, I had taught candidates and orders.

What played into this choice was an explicit desire to operationalize the conciliar choices. A space for lay people and women. I was a woman and laywoman and had the necessary qualifications. All the more so because already in the very early 1970s the Italian Nella Filippi and the Australian Rosemary Goldie, one of the 23 auditors of Vatican Council II, were teaching theology in Rome. The former, thanks to a path that had accelerated her time, having obtained her doctorate, she had been invited to teach Christology. The second, who had been called upon due to her widespread fame, was thus being rewarded for her missed role as undersecretary at the Pontifical Council for the Laity.

Elsewhere in Europe, women were also beginning to teach. First and foremost was the Dutch Katharina Halkes, due to her widely respected reputation; she was called by the Catholic University of Nijmegen to the chair of Feminism and Theology. To say nothing of the many whose studies were profoundly affecting the elaboration of a militant theology, notably different from that hitherto elaborated by men. There was no longer to be a theology in which the specification “of the woman” had an objective valence, but a theology of women (subjective genitive) about women or simply a theology elaborated by women - I cite the Norwegian Kari E. Børresen to whom we owe fundamental studies accompanied by an evocative and unprecedented vocabulary.

It is not, however, that all was well in the Church for women. They were called into question in the three issues Paul had avowed to them: women’s ministry, ecclesiastical celibacy, and birth control. The most disorienting “no” that nevertheless did not close the issue was the one concerning ministry. Meanwhile, the Church was in her own way involved in the International Year of Women celebrated by the United Nations in 1975. The Vatican also set up a study commission that came to little or nothing. Certainly two women had been proclaimed “doctor of the Church”, but Paul himself had to justify himself there in the face of the adage already mentioned concerning their silence in the Church.

Let me say that women were running fast, but the Church was struggling to meet their demands. A crack was widening that was difficult to heal, despite efforts in some paragraphs (numbers 34 and 35) of the 1974 Apostolic Exhortation Marialis Cultus. The women theologians were making a feminist field choice; they were abandoning the theology of women in order to make “a difference theory” their own, and to follow they would pay attention to all declinations of feminist thought, including radical, interjecting or acquiring gender theories and queer theories themselves.

This arduous dialogue, often between the hard of hearing, has seen women and the Church on divergent positions. The Church and its Magisterium have been reproached for never having abandoned the so-called “mystique of femininity” thus drawing an unreal woman, inscribed in the stereotypes that have been wrongly attributed to nature. The issue became entangled during the pontificate of John Paul II. His “feminism of difference” in fact took as a figure their capacity to generate and traced back to it their task in society as in the Church. There remained without an echo the titanic work of deconstruction and reformulation of faith that was produced by feminist reflection. I mention only by way of example, in the United States, Elizabeth Johnson, and her She Who Is, and not to forget Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza and her In Memory of Her.

As for me, I graduated in 1979. The Theological Faculty of Sicily was about to be erected and the license was no longer enough to be part of the staff. I was not given tenure in ecclesiology but in the theology of the laity. I continued, however, to teach it with growing passion. The women academics in Palermo were multiplying and by then the second generation of women researchers and teachers could be seen on the horizon. Moreover, in fact, where I had once begun, the fourth generation are operating today.

The women theologians of today do not have the concerns of those of those early times. I struggled so much to be able to teach while abandoning “neutral” language. In my early years, one had to prove oneself. Femininity had to be disguised somehow. I look with relief at younger female theologians who are sophisticated, pretty, mothers, married; in short, far removed from the asexual chiché of the consecrated to science and who were interested only in that.

In Italy, over the past decade, the sociologist Chiara Canta has devoted an essay suggestively titled The Discarded Stones to women theologians. In addition, recently, she has juxtaposed Pope Francis’ thinking related to women. Certainly, the situation is different today. Women theologians have affirmed their professionalism by establishing specific associations, national and otherwise - the CTI in Italy, for example. In addition, in other ecclesial spheres, women are more visible. Unresolved knots remain, however, women's ministry first and foremost among them. Clerical misogyny remains. In short, there is still an all uphill path that neither certain pastoral presence nor the recognition of Therese of Lisieux and Hildegard of Bingen as Doctors of the Church are enough to smooth out. For example, why not recognize others such as Edith Stein? Martyr yes and no one denies that, but a philosopher and theologian too; however, perhaps it is precisely because of that these figures are disorienting.

Yet, looking at the new generations, I feel full of confidence and optimism. The Church does not yet regard this tenacious cohort as a precious treasure, but I trust in times when this will happen. There is a need to reiterate the faith, to make it seductive again. Women theologians can do this; indeed, they are already doing so. It is necessary to make room for them across the board. It is no longer time for them to be silent but to speak and be heard.

by Cettina Militello

A theologian, and vice-president of the Via Pulchritudinis Academy Foundation.

Cettina Militello experienced the changes that Vatican Council II entailed for women firsthand. She was among the first in Italy to be admitted to a faculty of theology in 1968, and in 1975 among the first laywomen to teach in a theological faculty (that of Sicily). She devoted herself mainly to ecclesiology, Mariology, ecumenism, the women question, and the relationship between architecture and liturgy. She was a student and friend of Rosemarie Goldie, who was one of the 23 conciliar mothers. In addition, Cettina Militello is among the founders of the Coordination of Italian Women Theologians, established in 2003. She edited “Il Vaticano II e la sua ricezione al femminile,” [Vatican II and Its Reception by Women], Edb, which takes stock of the Council from a peculiar perspective: the innovation it entailed on the women’s side. Her latest books are Sinodalità e riforma della Chiesa. Lezioni del passato e sfide del presente [Synodality and Church Reform. Lessons from the Past and Challenges of the Present], published by St Paul Editions, and Le chiese alla svolta- Ripristinare i ministeri [Churches at the Turning Point-Restoring Ministries], Edb.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti