Politics is care

I was 11 years old when the Vatican Council II opened October 11, 1962. At the end of the first day, Pope John XXIII greeted the crowd gathered in St Peter’s Square with a caress, and the brief speech that has gone down in history, just like the address given by astronauts on the moon.

I was 14 when Paul VI, on December 7, 1965, announced the end of the work and the beginning of a path of human and religious renewal; thus delivering to the church the teaching “to love man in order to love God”.

I grew up in a simple family with strong religious and civic values. From an early age, I experienced a deep, authentic, and popular faith that was practiced and handed down to me by my parents.

The Council was really a new Pentecost, a shocking news for everyone, not only for Catholics.

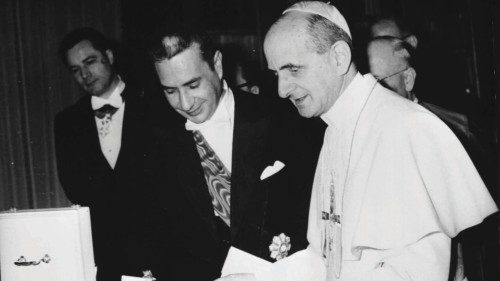

At a very young age, I joined Catholic Action, and the association was the form that molded my being a believer and a citizen under the sign of the Second Vatican Council. Catholic Action was changing and Vittorio Bachelet, a jurist and politician, had been called to lead it. Paul VI asked the new president to rethink its mission to make the Church of Gaudium et Spes and Lumen Gentium visible and operative

These were the religious choice years, when the association rediscovered its formative and pastoral vocation. In addition, the centrality of the Word, the primacy of faith and abandoned all forms of political collateralism. Religious choice meant returning to the essentials of the Gospel and initiating a secular reading of historical reality.

As I approached adulthood and breathed in a breath of fresh air, I understood that the Christian faith was not a theory but a person, it was Jesus Christ, and it was the Gospel. I was discovering that the universal church is a church of many local churches and the new liturgy in Italian a truly communal experience. The Church that values freedom of conscience, the search for truth rather than its imposition, and scrutinizes the signs of the times with a trusting gaze full of mercy.

The implementation of the Council, entrusted to Monsignor Enrico Bartoletti of the Italian Bishops' Conference (IEC), and to Vittorio Bachelet in Catholic Action, was not a foregone conclusion. It was not enough to adapt the structure of the association, for it was necessary to invest the parishes in a capillary way with a new catechesis aimed at young people and families, and the life of charity and co-responsibility.

A pillar of my formation was Paul VI’s apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi, which asked the laity to realize the kingdom of God through the things of the world. I understood what responsibility and freedom of the laity meant, which was one of the great gifts of the Council.

In the passionate climate of ecclesial renewal, politics presented itself as a place of mission. Faith, which does not allow itself to be imprisoned in any political project, urges us to do our part, in a relationship that is never one of overlapping or separation but always one of distinction. You learn then that secularity means taking responsibility for society and history independently, to pursue the common good and realize the City of Man.

Politics was thus the natural landing place of a pedagogy for citizenship that had matured hand in hand with my religious training.

The Council had read the signs of the times but the times had come with a lot of contradictions, lacerations and conflicts.

The year 1968 and the workers’ struggles, women’s leading role in feminism, new environmentalist sensibilities, tensions toward new freedoms and civil rights, and finally terrorism had laid bare great fractures in the relationship between institutions and society, democracy and politics.

Living through the Council in that decade from 1968 to 1980 meant growing up with the awareness that it was not enough to be good Christians-as Bachelet repeated-we also had to be good citizens.

In many, we felt the need for a new Christian-inspired way of thinking, which was capable of giving new life to Catholics’ political action by taking note of the divisions that, starting with the referendum on divorce, were invading our world.

The path of cultural and political change, which was initiated by the most advanced component of democratic Catholicism, was tragically interrupted with the kidnapping and killing of Aldo Moro at the hands of the Red Brigade. It is no accident that political terrorism struck some of the most lucid and far-sighted Catholic personalities such as Aldo Moro, Piersanti Mattarella, Vittorio Bachelet, and Roberto Ruffilli. These men were the interpreters of a vision of democracy and society that helped write the Constitution and build the new Republic.

That generation practiced secularism with a rare aptitude for mediation, in awareness of the relationship between rules and values, guided by a sense of limit and the principle of non-satisfaction that made Moro say, “Our destiny is not to achieve justice but to hunger and thirst for it all our lives”.

A lesson of secularism and moral rigor that I have tried to follow, ever since Maria Eletta Martini, head of the Christian Democratic Party for relations with the Catholic world, suggested that I run for the European Parliament, in 1989 at the end of my term as national vice-president of Catholic Action.

With the failure of Aldo Moro’s project, the most innovative energies clashed with the opacities of the party form. Christian Democracy, which was identified as the Catholics’ party, was no longer able to respond to the expectations of Italians. Moreover, the series of judicial investigations into corruption involving politics and business that journalistically took the name ‘Tangentopoli’ was the final act of a wear and tear that had been in place for some time.

For those who, like me, had begun service in institutions with the ambition of reviving the values of democratic Catholicism, the investigation also significantly called ‘Mani Pulite’ had to be read as an opportunity for ethical regeneration of politics.

On the ecclesial front, it was noted that the unity of Catholics would not stand up to the new bipolar arrangement, which was the result of the new majoritarian electoral law. With the demise of Christian Democracy, which had historically played a role in translating secular Christian inspiration into politics, the Italian church sought to fill this void by assuming its own social and political subjectivity to initiate a direct relationship with the country's institutions. This turn of events weakened the Italian Bishops’ Conference, which was no longer dialoguing without mediation with the different political alignments. Gone was that method of dialogue and synthesis, based on discernment that measured consistency between political choices and religious inspiration. In fact, a neo-clerical and conservative interpretation of the role of Catholics prevailed, which encouraged the instrumentality with which religion and ethically sensitive issues were addressed by the center-right.

I recall the clashes on the “end of life”, on the “legal recognition of de facto and homosexual couples”, on “assisted procreation” and the hierarchy’s invitation to desert the related referendum. All junctures in which the political interventionism of the Italian Bishops’ Conference on so-called nonnegotiable values-assumed as a priority on the political agenda at the expense of no less relevant issues. These include: the quality of democracy, inequalities, growing poverty, and immigration. Combined, these issues have accentuated the loneliness of those who in the wake of the Council’s lesson of secularism were laboriously seeking a synthesis between values and law, between Christian inspiration and the pluralism of Italian society.

That era should have left an indelible mark, because religion and values flaunted by the governing right wing today return to be wielded as banners of a Christian identity debased to political ideology. This ideological torsion is accompanied by a glaring inconsistency between the declared Christian inspiration and the concrete government choices on the terrain of fighting poverty and welcoming migrants. Perhaps it is no coincidence that in the Italian Parliament, for the first time, the presence of exponents of the Catholic world is very small, a sign of a shortsighted political offer, which has been unable or unwilling to intercept the vitality of a laity that in associations and parishes is at the service of the most fragile.

Pope Francis has repeatedly encouraged the engagement of Catholics in politics in the words of Paul VI’s “highest and most demanding form of charity” and clarified that “disengagement is tantamount to betraying the mission of the laity” who must be “salt of the earth and light of the world” even in institutions. However, he called for politics with a capital P, the kind capable of vision. “In the face of so many forms of politics that are petty and aimed at short-term interest, I remember that political greatness is shown when, in difficult times, one operates on the basis of great principles and thinking about the common good in the long term”.

With his invitation to be a synodal and outgoing Church, the Holy Father indicates a path of renewed implementation of the Council to the laity as well. In addition, the preferential choice for the poor, the attention to the existential and material peripheries of the world, the denunciation of the profound inequalities generated by a globalization without rules, the unceasing prayer for peace in the world, following in the footsteps of the prayer with all religions desired by John Paul II in Assisi, the condemnation of corruption and illegality, the intense pastoral care on the safeguarding of creation and fraternity without frontiers, are precious indications for anyone who hungers and thirsts for justice. Politics is care for the common good, this I learned from Council. Only a politics free of interests, which cares for the community, can do justice for the poor and the peripheries of the world, as Pope Francis asks us to do.

by Rosy Bindi

Italian politician, lecturer at the Pontifical Antonianum University, president of the National Committee Centenary Birth of Don Lorenzo Milani. She has been national vice-president of Catholic Action, a Euro parliamentarian, minister of Health and minister of the Family, vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies; president of the Democratic Party, president of the Parliamentary Anti-Mafia Commission.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti