He was born in a country on the extreme periphery of the Roman Empire. A country proud of its traditions and faithful to its monotheism even though it was surrounded by polytheistic cultures. He was born among a people stubbornly attached to their identity, who have always resented any foreign domination. He was born in a border town, and on the radar of great history, his story - destined to become a central event in that of the whole of humanity, dividing it chronologically in two - would at the time have been nothing more than an insignificant speck. Even for his preaching, in the three years of his public life, he preferred the peripheral lands. Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of the God who overthrows “the mighty from their thrones” and raises up “the lowly”, the God who chose a 14-year-old girl from an unknown village in Galilee as the protagonist of the joint-venture of the incarnation to save mankind, was for his entire earthly existence, a man of the borderlands.

From the very beginning, his life was marked. Mary and Joseph, who were forced to travel because of the census, leave Nazareth to reach Bethlehem, steeped in history as the city of the lineage of David, a small town not far from Jerusalem. The lack of a place away from prying eyes in the caravanserai forces them to find a makeshift shelter in one of the many caves used as stables. Here, in absolute precariousness, the “King of Kings” is born, the Messiah Son of the Almighty, reduced to helplessness and totally dependent on the care of a mother and a father, like every newborn that comes into the world. A few months pass, and that scene, which we are used to reproducing somewhat sweetly and idyllic by celebrating Christmas, is tinged blood red. It is the blood of the innocent, victims of King Herod, who has all the children in Bethlehem under two years of age slaughtered in order to get rid of the Messiah. Little Jesus is saved. He and his family have the experience of so many migrants and refugees in history. They leave their country, cross a border, adapt to living among another people with a different culture and traditions. They survive thanks to the Egyptians’ welcome.

Dio non sceglie per suo Figlio, il Messia a lungo profetizzato e atteso dal popolo di Israele, i palazzi del potere mondiale, quelli di Roma, né quelli del potere in Israele, quelli di Gerusalemme. Il Nazareno muove i primi passi della sua vita lontano dalle capitali politiche e religiose. È un Re che nasce nell’umiltà e nel nascondimento, ricevendo l’omaggio degli emarginati, i pastori che vivevano fuori dai villaggi con le loro greggi e venivano considerati nomadi dai quali stare alla larga.

God does not choose for his Son, the Messiah long prophesied and awaited by the people of Israel, the palaces of world power, those of Rome, nor those of power in Israel, those of Jerusalem. The Nazarene takes the first steps of his life far from political and religious capitals. He is a King born in humility and concealment, receiving the homage of the outcasts, the shepherds who lived outside the villages with their flocks and were considered nomads to be kept away from.

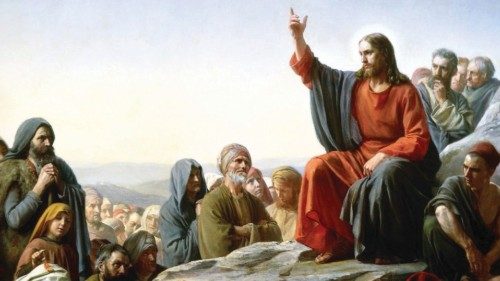

Then, after decades of life hidden in Nazareth, Jesus begins his public life. His preaching did not begin in Jerusalem, but on the outskirts of Galilee, a region regarded with some contempt by the most observant Jews because it was a place where people mingled and where foreign populations lived. Galilee is a land of transit, of trade. It is a multicultural and multilingual land, where races, cultures and religions intersect and meet. It is the “Galilee of the Gentiles” (Isaiah), the favoured land of the Son of God, who chooses a fishing village called Capernaum, as his base. The town is built on the shore of Lake of Gennesaret, that “Sea of Galilee” that he and his apostles, almost all fishermen, will cross far and wide, travelling by boat. While entering and teaching in synagogues, Jesus meets people in the streets, at crossroads, on the lakeshore or as he moves from one village to another accompanied by the small group of his followers.

When he has to choose his own, he surrounds himself with men who do not come from the schools of the doctors of the law, the scribes, or the men of religion. He prefers people who are humble, simple, dedicated to manual labor. He calls them to himself, going to "fish" for them one by one where they work, where they live.

The Son of God’s predilection is for those on the margins, those who are or feel rejected, those who are excluded, the unpresentable and the untouchable. Jesus calls tax collectors like Matthew or the unpresentable leader of the publicans of Jericho, Zacchaeus. He does not just talk to them, but makes gestures that break with the traditions of the time, going to their homes. He is not afraid to cross the thresholds of the dwellings of the pagans, he is not afraid to touch those who are “unclean” because they are sick - like the lepers that Mosaic tradition confined outside the cities in order to avoid contagion - or because they are sinners. Jesus meets them, he “infects” himself. Indeed he tells his own, who accompany him at that moment without fully understanding his message, that he has come for sinners, not for the righteous. For the sick, not the healthy. Thus he heals the 'impure' bleeding woman who touches the hem of his cloak. He embraces the hardened and corrupt sinner Zacchaeus, who is converted because he is inundated with this infinite mercy; he saves the woman caught in flagrant adultery, from being stoned and forgives driving away the well-wishers who were ready to throw stones at her after he had escaped their insidious questions by remaining silent; in the Pharisee’s house Simon allows himself to be washed and dried by the sinful woman whose sins he forgives because she 'loved so much'. He is ready to enter the home of a pagan, the Roman centurion, who begs him to heal his servant. After the latter describes himself as “unworthy” to welcome the Messiah into his home, Jesus points him out to his disciples as a model, saying that he has not found such great faith in anyone belonging to the chosen people of Israel. The sick, the crippled, the possessed are his daily bread, the people he passes on the dusty roads of the Galilean villages. He goes after those who do not feel “right”, those who live unbalanced, those who are outside. He restores sight to the blind, who 'see' more than the sighted and call out to him to get his attention.

Even in the Galilee of the Gentiles, Jesus always lives on the border, because he never gets caught up in the plans of the rebels who would like to use him as the banner of the struggle against the Roman invaders. Hence, after all, the disappointment of the apostle Judas, who until the very end hoped for a messianic ‘manifestation’ accompanied by worldly power. Whenever the crowds want to crown him king, the Nazarene flees, he hides, to the ends of the earth, because the Kingdom of God that he came to announce is in this world but is not of this world. It is the proclamation of an Almighty God who renounces power by choosing the path of lowering himself, of humility, of sharing with the poorest and the lowliest.

Even what then appeared to be the last chapter of this story, that being death on the cross, we see him being hung outside the walls of the Holy City of Jerusalem. There he is naked and discarded like an infamous man. He accepted to die like a sacrificial lamb without a reaction, thus showing by his own example the way of non-violence. His death on the cross had seemed the greatest defeat, the miserable end of everything; instead, on the third day he rises again, as he had foretold to his own people. But again, the Son of the God who prefers to be found in the gentle breeze rather than in the earthquake, the Son of God who never overrules the freedom of man, by always leaving enough light for those who want to believe and enough darkness for those who do not want to believe, and shows himself first to the women. He does not appear to Herod Antipas in the palace in Jerusalem, nor to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, nor to the high priests Annas and Caiaphas. He shows himself to women, whose testimony, in the macho society of the time, was worth nothing in court. Once again turning all human logic upside down.

By Andrea Tornielli

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti