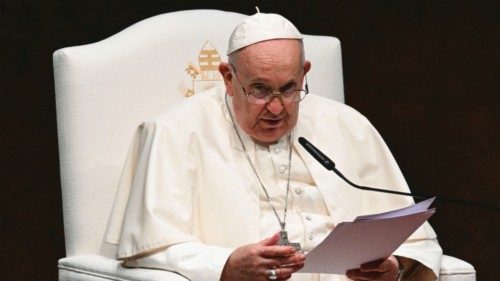

On his arrival at Lisbon’s Figo Maduro Air Base on Wednesday morning, 2 August, the Holy Father was welcomed by the President of the Republic of Portugal, H.E. Mr Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, and by two children who offered him flowers. After the official welcome with the Guard of Honour and the greeting of the Delegations, Pope Francis travelled by car to Palácio Nacional de Belém, where he signed the Book of Honour and had a private meeting with President de Sousa, before heading to the Centro Cultural de Belém for a meeting with Authorities, Civil Society and the Diplomatic Corps. The following is the English text of the Pope’s address to them.

Mr President of the Republic,

Mr President of the Assembly of the Republic,

Mr Prime Minister,

Members of Government and the Diplomatic Corps,

Authorities, Representatives of Civil Society and the world of culture,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I greet you cordially, and I thank the President for his welcome and kind words. The President is very welcoming. Thank you! I am happy to have come to Lisbon, this city of encounter which embraces many peoples and cultures, and which, in these days, is even more global: in a certain sense, it has become the capital of the world, the capital of the future, because the young are the future. This very much befits its multiethnic and multicultural character — I think of the Mouraria district, where people from more than sixty countries live together in harmony — and it displays the cosmopolitan face of Portugal, grounded in a desire to be open to the world and to explore it, setting sail towards ever new and vaster horizons.

Not far from here, at Cabo da Roca, are sculpted the words of the great poet of this city: “Here… where the land finishes and the sea begins” ( L. Vaz de Camões , Os Lusíadas, iii , 20). For centuries, people considered that place to be the end of the earth, and in some sense, it is: we find ourselves at the end of the earth because this country borders the ocean, which defines the continents. Lisbon reflects the ocean’s embrace and bears its fragrance. I too sense what the Portuguese people love to sing: “Lisbon, redolent of flowers and the sea” ( A. Rodrigues , Cheira bem, cheira a Lisboa, 1972). That sea is much more than part of the landscape: it is a call resounding in the heart of every Portuguese person: “the crashing sea, the bottomless sea, the infinite sea”, as one of your local poets has called it ( S. de Mello Breyner Andresen , Mar sonoro). Gazing at the ocean, the Portuguese people reflect on the immense reaches of the soul and the meaning of our life in this world. I too, inspired by the image of the ocean, would like to share with you some thoughts.

In classical mythology, Oceanus is the child of the sky (Uranus): its vastness leads mortal men and women to lift their gaze on high and to rise up towards the infinite. Yet Oceanus is also the child of the all-embracing earth (Gaia), calling us to embrace with tenderness the entire inhabited world. The ocean does not merely link peoples and countries, but lands and continents. Lisbon, as an ocean city, thus reminds us of the importance of the whole, to think of borders as places of contact, not as boundaries that separate. Today we realize that the great questions facing us are global, yet we often find it hard to respond to them precisely because, faced with common problems, our world is divided, or, to say the very least, insufficiently cohesive, incapable of confronting together what threatens us all. Planetary injustice, wars, climate and migration crises: these seem to run faster than our ability, and often our will, to confront these challenges in a united way.

Lisbon can suggest a different path. It was here, in 2007, that the Treaty for the reform of the European Union was signed. That Treaty, named after this city, affirmed that “the Union’s aim is to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples” (Treaty of Lisbon, Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community, art. 2:1). Yet it goes beyond that, asserting that “in its relations with the wider world… It shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and the protection of human rights” (art. 2:5). Those were not only words, but milestones along the path of the European community, and are impressed on this city’s memory. This is the spirit of being together, inspired by the European dream of a multilateralism broader than merely that of the West.

According to a debatable etymology, the name Europe derives from a word meaning the direction west. What is certain is that Lisbon is the most westerly capital of continental Europe and thus speaks to us of the need to open ever broader paths of encounter. Portugal is already doing this, above all with countries of other continents that share the same language. It is my hope that World Youth Day may be, for the “Old Continent” — we can say the “Elder Continent” — an impulse towards universal openness, an impulse that makes it younger. For the world needs Europe, the true Europe. It needs Europe’s role as a bridge and peacemaker in its eastern part, in the Mediterranean, in Africa and in the Middle East. In this way, Europe will be able to make its own specific contribution in the international arena, based on the ability it showed in the last century, in the aftermath of the world wars, to achieve reconciliation and to realize the vision of former enemies joining together to work for a better future. This goal was attained by initiating processes of dialogue and inclusion and by developing a diplomacy of peace aimed at settling conflicts and lessening tensions, attentive to the slightest signals of distension and reading between the most crooked lines.

We are sailing amid storms on the ocean of history, and we sense the lack of courageous courses of peace. With deep love for Europe, and in the spirit of dialogue that distinguishes this continent, we might ask her: “Where are you sailing, if you are not showing the world paths of peace, creative ways for bringing an end to the war in Ukraine and to the many other conflicts causing so much bloodshed?” Or again, to widen the scope, we might ask: “West, on what course are you sailing?” Your technologies, which have brought progress and globalized the world are not by themselves sufficient, much less your highly sophisticated weapons, which do not represent investments for the future but a depletion of its authentic human capital: that of education, health, the welfare state. It is troubling when we read that in many places funds continue to be invested in arms rather than in the future of the young. This is true. An economist was telling me a few days ago that the best investment income comes from the production of arms. We are investing more in arms than in the future of children. I dream of a Europe, the heart of the West, which employs its immense talents to settling conflicts and lighting lamps of hope; a Europe capable of recovering its youthful heart, looking to the greatness of the whole and beyond its immediate needs; a Europe inclusive of peoples and persons, together with their own cultures, without chasing after ideologies and forms of ideological colonization. This helps to bring us back to the dream of the founders of the European Union. They had a great dream!

The ocean, this immense expanse of water, recalls the origins of life. In today’s developed world, paradoxically, the defence of human life, menaced by a creeping utilitarianism that uses life and discards it — a culture that discards life, has now become a priority. I think of so many unborn children, and older persons who are abandoned, of the great challenge of welcoming, protecting, promoting and integrating those who come from afar and knock on our doors, and the isolation felt by so many families that find it hard to bring children into the world and raise them. Here too, we might ask: “Where are you sailing, Europe and the West, with the discarding of the elderly, walls of barbed wire, massive numbers of deaths at sea and empty cradles? Where are you sailing? Where are you sailing if, before life’s ills, you offer hasty but mistaken remedies: like easy access to death, a convenient answer that seems ‘sweet’ but is in fact more bitter than the waters of the sea?” I am thinking here of many advanced laws concerning euthanasia.

Lisbon, surrounded by the ocean, nonetheless gives us reason to hope. It is a city of hope. A sea of young people is pouring into this hospitable city. Here I would like to express my gratitude for the hard work and generous efforts shown by Portugal in hosting an event so challenging to organize, yet so rich in hope. As a local saying goes: “In the company of the young, we never grow old”. Young people from around the world, who dream and long for unity, peace and fraternity, urge us to make their good dreams come true. They are taking to the streets, not to cry out in anger but to share the hope of the Gospel, the hope of life. At a time when we are witnessing on many sides a climate of protest and unrest, a fertile terrain for forms of populism and conspiracy theories, World Youth Day represents a chance to build together. It revives our desire to accomplish something new and different, to put out into the deep and to set sail together towards the future. We are reminded of those bold words of Pessoa: “to set sail is necessary, to live is not… What is important is to create” (Navegar é preciso). So let us resolve, with creativity, to build together! I would like to suggest three construction sites of hope in which all of us can work together: the environment, the future, and fraternity.

The environment. Portugal, together with Europe, has made outstanding contributions to the protection of creation. Yet on the global level, the problem remains extremely grave: the oceans are warming and their depths are bringing to light the shamelessness with which we have polluted our common home. We are transforming great reserves of life into dumping grounds of plastic. The ocean reminds us that human life is meant to be an integrated part of an environment greater than ourselves, one that must be protected and watched over with care and concern for the sake of future generations. How can we claim to believe in young people, if we do not give them healthy spaces in which to build the future?

The future is the second construction site. Young people are the future. Yet they encounter much that is disheartening: lack of jobs, the dizzying pace of contemporary life, hikes in the cost of living, the difficulty of finding housing and, even more disturbing, the fear of forming families and bringing children into the world. In Europe and, more generally, in the West, we are witnessing a decline in the demographic curve: progress seems to be measured by developments in technology and personal comfort, whereas the future calls for reversing the fall in the birth rate and the weakening of the will to live. A healthy politics can accomplish much in this regard; it can be a generator of hope. It is not about holding on to power, but about giving people the ability to hope. Today more than ever, it is about correcting the imbalances of a market economy that produces wealth but fails to distribute it, depriving people of resources and security. Political life is challenged once more to see itself as a generator of life and concern for others. It is called to show foresight by investing in the future, in families and in children, and by promoting intergenerational covenants that do not cancel the past but forge bonds between young and old. We need to resume a dialogue between young and old. This is encouraged by that sense of saudade, which in the Portuguese language expresses a kind of nostalgia, a yearning for an absent good that is born of contact with our roots. The young must find their roots in the elders. Here, education is essential: an education that does not simply impart technical knowledge directed to economic growth, but aims to make the young part of a history, to pass on a tradition, to value our religious dimension and needs, and to favour social friendship.

The final construction site of hope is fraternity, which we Christians learn about from Jesus Christ. In many parts of Portugal, we encounter a lively sense of closeness and solidarity. Yet in the broader context of a globalization that brings us closer but fails to create fraternal closeness, all of us are challenged to cultivate a sense of community, beginning with concern for those who live close by. For, as Saramago observed, “what gives true meaning to encounter is concern for others, and we have to travel far to arrive at what is near” (Todos os nomes, 1997). How beautiful it is to realize that we are brothers and sisters and to pursue the common good, leaving behind our conflicts and differing viewpoints! Here too, we can see an example in those young people who, with their pleas for peace and their thirst for life, impel us to break down the walls of separation erected in the name of different opinions and creeds. I have come to see how many young people long to draw closer to others: I think of the Missão País initiative, which leads thousands of young people, in the spirit of the Gospel, to share experiences of missionary solidarity in the peripheries, especially in villages in the interior of the country, and to go out in search of elderly people who are living alone. This is an “anointing” for young people. I would like to thank and encourage them, and all those in Portuguese society who show concern for others, as well as the local Church, which quietly and unobtrusively does so much good.

Brothers and sisters, let us all feel called, in a fraternal way, to give hope to the world in which we live, and to this magnificent country. God bless Portugal!

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti