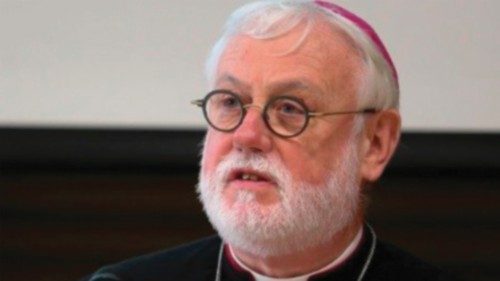

Speaking at the presentation of the volume, “Lezioni ucraine” (Ukrainian Lessons), published by “Limes”, Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher, Vatican Secretary for Relations with States and International Organizations, illustrated “the position taken by the Holy Father with regard to the war in Ukraine and the interpretations given to his words and gestures”.

Indeed, he said, “it is indisputable, and it is also honest to acknowledge that “the reaction of the people of Ukraine to Pope Francis’ declarations reflects profound disappointment” (p. 86 of the book). This, in fact, was made evident by Ukraine’s government leaders as well as by various religious representatives of the local Churches and ecclesial communities, in some cases even recently. The Pope’s public words and gestures are given as fact, and an interpretation of them can rightly be given freely and with discretion”. However, the Archbishop stressed, “interpreting them as ‘acts of empty pacifism’ and ‘theatrical’ expressions of ‘pious desire’ (p. 87) does not do justice to the vision and intentions of the Holy Father, who does not want to resign himself to the war and who stubbornly believes in peace, inviting everyone to be creative and courageous weavers and artisans of peace”.

In fact, he explained, “what moves the Holy Father is nothing but the will to make dialogue and peace possible, inspired by the principle that ‘the Church must not use the language of politics, but the language of Jesus’. It is thus wrong to describe the ‘Vatican’s attempts as useless and dangerous’ and to label as blasphemous ‘the Vatican’s anti-Americanism’ (p. 87)”. Surely, “it is not the Holy See’s intention to ‘look the other way before the systematic war crimes by the Russian army and authorities and to place an aggressor country and an attacked one on the same level’ (p.87), because the Pope himself clearly said that he made the distinction between aggressor and attacked, with the incontestable certainty that the whole world knows well which is which. Incidentally, precisely through actions and with “all the humanitarian initiatives and gestures made in favour of the people of Ukraine’ (p. 87), the Pope has clearly shown on a concrete level, who the aggressor is and who the victim is”.

Therefore, he continued, we must “recognize that the Holy Father’s gestures and words are not merely an expression of ‘a rhetoric of peace’, but of a strong and courageous ‘prophecy of peace’, which challenges the reality of war and its supposed unavoidability. This prophecy however, rather than being welcomed and sustained so that it may be more easily enacted, is rejected and condemned, with a spirit that, in this way, proves to be no less partial than what is being attributed to the Holy See”.

Moreover, Archbishop Gallagher acknowledged his own surprise for the way in which the topic of diplomatic presence on the territory is being addressed: “while great appreciation and gratitude is expressed to the embassies that, faced with the Russian march towards Kyiv, did not leave the country, but only moved to Lviv, not even the smallest mention is made of the fact that, faced with the same threat, the apostolic nuncio remained in the Ukrainian capital, sustained by Pope Francis’ public appreciation and gratitude. Such a decision by the pontifical representative clearly shows that the Holy See’s desire is not that of wanting ‘to play a part’ (p. 25) in the tragic Russian war in Ukraine, but of showing concrete Christian closeness to a battered people and to give oneself for peace”. In this sense, the involvement of the local Catholic Church, of both Latin and Eastern rites, is also noteworthy, “as is that of different Catholic charitable organizations, above all in the humanitarian sphere, without forgetting the numerous missions carried out in Ukraine by Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, the Almoner of His Holiness. All this can undoubtedly be considered as a sort of ‘charitable embrace’, with which the Holy Father has held the people of Ukraine, not leaving them alone in the suffering and tragedy they are experiencing”. It is therefore opportune to give preference to “the duty that we all have to truth, which is the first victim in every war and, above all, to the shared responsibility to promote everything that might help move the current tragedy in a positive direction”. Because the war in Ukraine, which is a “great war” that shocks Europe (and increasingly involves the whole world), is above all “a tragedy to overcome, and the same effort to understand must not be limited to being merely a speculative effort, but must facilitate the arduous search for exit paths”.

Today, Archbishop Gallagher explained, there are “some attitudes that must change in order to foster peace”. First of all, “contrary to the current global trend”, a change “that involves the ‘logic of war’, which unfortunately continues to dominate, whether in relation to the outcome of the conflict, or under the justification of necessary defense”. In short, “the idea that nothing can be done, that there is no room for words, for creative dialogue and for diplomacy, that it is necessary to resign oneself to and accept the continuation of the ferocious fighting that sows death and destruction”, must not prevail. There is the need for “small changes that make certain strategies possible and open the mind and heart to the other”. For this reason, “the tendency to justify mistrust in others must be overcome through an even greater effort to build mutual trust. In this sense, it can be of real help to strengthen the humanitarian initiatives that are already underway, such as the one on the exchange of prisoners of war or on grain exports, and the one on the repatriation of children, which Cardinal Matteo Zuppi is trying to set in motion following his double mission in Kyiv and Moscow”. This war, the Archbishop concluded, “must be stopped as soon as possible”.

Roberto Paglialonga

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti