Theological Point

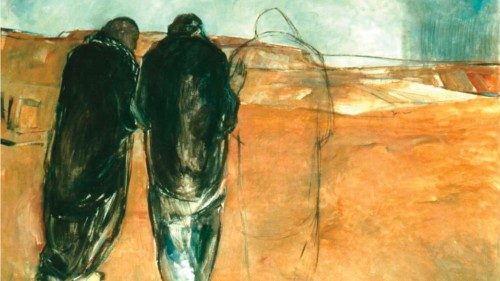

That very day two of them were going to a village named Emma′us, about seven miles[a] from Jerusalem, 14 and talking with each other about all these things that had happened. While they were talking and discussing together, Jesus himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were kept from recognizing him. And he said to them, “What is this conversation which you are holding with each other as you walk?” And they stood still, looking sad. Then one of them, named Cle′opas, answered him, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” And he said to them, “What things?” And they said to him, “Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since this happened. Moreover, some women of our company amazed us. They were at the tomb early in the morning and did not find his body; and they came back saying that they had even seen a vision of angels, who said that he was alive. Some of those who were with us went to the tomb, and found it just as the women had said; but him they did not see.” And he said to them, “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.

So they drew near to the village to which they were going. He appeared to be going further, but they constrained him, saying, “Stay with us, for it is toward evening and the day is now far spent.” So he went in to stay with them. When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened and they recognized him; and he vanished out of their sight. They said to each other, “Did not our hearts burn within us[b] while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the scriptures?”. And they rose that same hour and returned to Jerusalem; and they found the eleven gathered together and those who were with them, who said, “The Lord has risen indeed, and has appeared to Simon!”. Then they told what had happened on the road, and how he was known to them in the breaking of the bread.

Luca 24, 13-35

The long page in Luke’s gospel recounting the experience of the disciples of Emmaus (24:13-35) is paradigmatic. It does not narrate an episode, but proposes a model. With the account of the two of Jesus’ disciples, who experience the transition from their master’s crucifixion and death to faith in his resurrection, Luke decisively, definitively lays out the Christian catechesis manifesto, and calls for perseverance in living out the cornerstones of faith. First and foremost, Ecclesial faith is experienceable and experienced as faith shared and celebrated.

Indeed, Luke wrote at a time when the expectation of “Parousia” had become less pressing. This was the time in between, between the Resurrection and the second coming in which, progressively, the life of the communities was being increasingly shaped and for the better, and the experience of sacramentality was becoming more and more decisive. The Risen One’s Spirit gives meaning and, above all, efficacy to the words and gestures that Christians perform in liturgical gatherings. In short, the evangelist lived at a time when the liturgical celebration, particularly that of the breaking of bread, had become the space in which an encounter with “the living among the dead” as the angels had promised women on Easter morning is possible (Luke 24:5). It is possible to understand him only if one accepts the entering into a paradoxical logic, that is, if one comes to go beyond what is seen, to see what is not seen. This is the logic that presides over liturgical experience. In the Lucan narrative, the main elements of apostolic preaching unfold as stages in a progressive unveiling that enables two of Jesus’ disciples to “adjust their eyes” so that finally the image of Jesus and that of the Risen One come to overlap and coincide.

It cannot be forgotten, however, that for the Christian tradition, there can be no liturgy, that is, no celebration of a reality, that is, the presence of the Risen One, through its symbolic expression, without the contribution of the word. This word expresses itself in all its versatility, as proclamation, as teaching, as a prayer of praise or of request. This is why the link between the Bible and the liturgy is so stringent. The writings of the New Testament were founded and transmitted within the celebrations of the first Christian churches, and even today, after two thousand years, there is no - or, perhaps better, there should be no - authentically Christian rite that is not rooted in the proclamation or reading of that Scripture venerated as the Word of God. That is why it can only be cause for grief to note that the separation between the churches that has torn the one Church of Christ apart over the centuries passes precisely through the breaking of this original bond between word and symbol, which is no longer reciprocal but in opposition.

Yet that Page of Luke’s gospel is there to remind our churches that the Risen One is made recognizable to all generations of disciples only through the experience of sacramentality. The Spirit of the Risen One gives meaning and, above all, efficacy to the words and gestures Christians make in liturgical gatherings and thus enables the absence of the earthly Jesus to be transformed into a new form of presence. Imaginary, for those who do not believe, and for those who do believe, an experience of a different form of reality.

The Word-Eucharist polarity receives great force from the Emmaus story. Luke emphasizes that in order not to leave the symbol to arbitrariness and thus condemn it to insignificance. The reference to the Scriptures must be to “all” the Scriptures and must be a “systematic” reference, that is, capable of taking them in both their diversity and their historicity and grasping their common tension toward the final fulfillment, in the story of the Messiah, of divine intervention in human history, the ultimate and final creation.

Only in this way is Easter faith not simply reduced to an enthusiastic outburst or an ecstatic experience, but neither is it reduced to a philosophical-religious reflection. Only in this way, however, does access to the mystery celebrated in the Eucharistic sign, in the gesture of bread being broken and shared, become possible. For knowledge of the biblical God makes the heart burn and opens the eyes (Luke 24:32). Not in an emotional or sentimental sense. No electrocution, but the slow pedagogy that leads, when word and sign finally open mutually and the power of the Word makes the sign transparent, to recognize the presence of the one who is not to be sought among the dead because he is alive. After all, for Christians the liturgy is the place where we learn the words to “think” the resurrection and “say” the resurrection. Moreover, this is not a matter of high-emotional religiosity, for it calls for knowledge of all the Scriptures of Israel because only from Moses and the Prophets can one understand Jesus and his gospel and because only Scripture educates one to enter into the logic of signs as an unveiling of the God who makes himself present.

Luke knows very well that without biblical catechesis and the sacramental celebration, the Risen One is nothing but reverie, imagination, illusion, and Christian faith results in one of many forms of abuse of popular credulity.

by MARINELLA PERRONI

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti