TheProposal

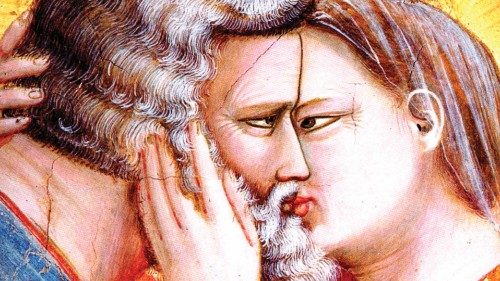

Kissing someone, kissing an object, hugging, exchanging a kiss, are rituals that accompany our daily life, but also our Christian celebration. As it is a gesture with a strong relational implication, in the liturgy it is reserved for special occasions. One kisses the presence of Christ in his main sacramental signs exclusively, the altar, and the evangeliary. For this reason, a kiss is always associated with the gesture of worship and is accompanied most often by silence or a prayer whispered in the heart. Only in the second instance does this gesture extend to the presence of God in the brethren in the kiss of peace. All other kisses of devotion, addressed to sacred images and objects (such as the cross, stole, statues, relics, etc.) are, in a sense, an extension of this. Indeed, kissing is a gesture of strong symbolic value and intense inner involvement, while excessive multiplication debases its value.

It was the liturgical reform of the Second Vatican Council that called for it to be particularly precious, to be reserved exclusively for the two culminating moments of the Eucharistic celebration: the kissing of the Gospel, the summit of the Liturgy of the Word, and the kissing of the altar, the center and culmination of the entire Eucharistic celebration. The rite, in fact, includes the kissing of the altar in the dynamics of greeting (entrance rites) and farewell (conclusion rites), as if to knot together, in a single action, the greeting to Christ with his very body, the Church. A kiss, which is so deeply linked to the mouth and to the symbolism of nourishment, holds a special initiatory and Eucharistic significance in the liturgy. In fact, just as it is a prelude to sexual relations, so it is of the moment of greatest involvement of the baptized person in the Eucharistic celebration. The mouth, in fact, represents that threshold between the outside and the inside, the entering and the leaving, of which the tongue mediates. In the liturgy, in fact, a kiss becomes the guardian of the thresholds (kissing the altar in the rites of entrance and in the rites of conclusion), invites entry and accompanies exit. In the rite of Baptism, too, the mouth becomes the protagonist of an initiation through the rite of Effata (open!). An initiatory gesture that every baptized person is called to relive every day through the holy touch of the fingers in the rite of the invitatory of the Liturgy of the Hours (O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will proclaim your praise). A gesture, a touch, a perception, a prelude to a fulfillment and satiety that only the Eucharist knows how to satiate and at the same time kindle new desire.

One must ask, then, why is the liturgy so restrained with kisses?

The answer is to be sought in the very nature of the liturgical celebration called to nourish, kindle and sustain, the time of the presence/absence of the Risen One. In fact, to the properly theological dimension of the liturgy, belongs also the play of desire: to touch lightly without withholding, to taste without satiating, to peek under the veil of symbols, to intuit without ever presuming to have understood. Hence, the predilection for igniting the senses with modesty and sobriety (“let us joyfully taste the sober intoxication of the Spirit” from an ancient liturgical hymn). Liturgy, in fact, does not take possession of the myster; instead, it brings it near and gives widely so that it may be believed, understood, to make us feel that even in its paradoxical familiarity with us, it remains inaccessible. So, too, in the liturgy the kiss is tasting. The disciple, in fact, is called to overcome the desire to possess the Master’s presence, as was the case for the bleeding woman, who clutches Jesus’ cloak in her hands (Mark 5:28-30), as for Mary Magdalene at the empty tomb (John 20:17). A Kiss and an embrace that, after the resurrection, becomes a warning and an expectation: Noli me tangere, do not hold me back, or, Noli me osculare. The disciple-lover after the resurrection, in fact, will no longer be able to find the Master and hold him and himself, but will be invited to a continuous wandering, tirelessly returning there where it all began, to Galilee (Matt. 28:7), the place of the first glimpse of love. As Pope Francis reminds us too:

The Gospel is very clear: we need to go back there, to see Jesus risen, and to become witnesses of his resurrection. This is not to go back in time; it is not a kind of nostalgia. It is returning to our first love, in order to receive the fire which Jesus has kindled in the world and to bring that fire to all people, to the very ends of the earth. Go back to Galilee, without fear!

“Galilee of the Gentiles” (Mt 4:15; Is 8:23)! Horizon of the Risen Lord, horizon of the Church; intense desire of encounter… Let us be on our way! (Homily of the 2014 Easter Vigil).

The ritual language is the site of this interplay of alternations: a continual coming and going in Galilee, a space in which to celebrate the dynamic between separation and conjunction with God, distance and closeness, otherness and intimacy, in the continual fluctuation between God’s acting power and man’s desire. What moves him, in fact, is desire, and what struck him is distance. All ritual logic moves in step with this sacred dance, made up of touches that kindle and distances that tear. In the liturgy, then, the kiss is tamed and redeemed from the temptation of longing but, at the same time, it announces and celebrates a reality that is already inhabited: a communion of breath, mouth, called to taste and praise with one voice that “The Lord is risen!” Is this not the gesture that will make the confession of the Name possible? The breath, the breath from Jesus’ mouth that gives life and restores soul to the community of frightened disciples inside an asphyxiated room (John 20:22). Jesus’ breath thus becomes the image of that space-time in which between Jesus’ mouth and the mouths of the disciples the expectation and desire for his return expands. The time of embraces and kisses given and received, just as the mouth of the bride in the Song of Songs sings, “O that you would kiss me with the kisses of your mouth” (Song 1:1). Finally, it should not be forgotten that the kiss preludes the act of love, thus the being of us all, our birth, life and death. In addition, if in fairy tales the kiss is capable of restoring life, breaking spells or transforming toads into princes, so it is in reality the kiss is a sure pledge of hope and of all transformation! In the poetry of David Maria Turoldo, the Servite friar who was one of the most representative figures of Catholicism in the second half of the 20th century, the kiss narrates the drama of the struggle between death and life, breath given and breath taken away:

You kisses me with kisses...but it is with the kiss

That He his breath again you take:

The breath that breathed mouth to mouth

Made you “persona vivens,” up there....

From that summit then begins

The great Contention

And Death with Love coexists.

And you have only one choice:

Inhale its breath

With the same passion....

The liturgical celebration must once again become a pleasant place in which to experience the sober intoxication of the Spirit. Seriousness and playfulness, truth and beauty, understanding and imagination, meditation and excitement, all these components of being human must be able to find their proper place and balance in the rite. If in the past there were passionate and extraordinarily emotional practices of piety, today our liturgies seem to either disdain all emotional forms or indulge them in unrestrained restraint. Liturgy becomes the teacher and guide of the affections: it nourishes them and at the same time contains them, enlightens and purifies them, enkindles and elevates them, and preserves that delicate boundary between externalization and reserve, thus educating us to the proper respect of intimacy.

Liturgy is like a kiss....

by MORENA BALDACCI

Theologian

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti