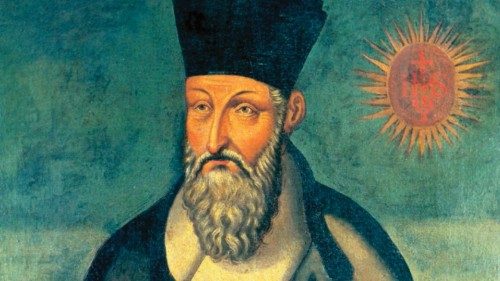

At the General Audience on Wednesday, 31 May, Pope Francis continued his series of catecheses on apostolic zeal, pausing on the figure of Venerable Matteo Ricci, one of the early Jesuit missionaries to the Far East, who fulfilled Saint Francis Xavier’s dream of entering China. Thanks to his writings in Chinese and his knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, the Pope observed, Matteo Ricci became known and respected “as a sage and scholar”. The following is a translation of the Holy Father’s words which he shared with the faithful gathered in Saint Peter’s Square.

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Good morning!

We are continuing these catecheses speaking about apostolic zeal, that is, what the Christian feels in order to carry out the proclamation of Jesus Christ. And today I would like to present another great example of apostolic zeal: we have spoken about Saint Francis Xavier, Saint Paul, the apostolic zeal of the great zealots; today we will talk about one — Italian, but who went to China: Matteo Ricci.

Originally from Macerata, in the Marches, after studying in Jesuit schools and entering the Society of Jesus, he was enthused about the reports he heard from missionaries. He became enthusiastic, like many other young people who felt the same; he asked to be sent to the missions in the Far East. After the attempt by Francis Xavier, an additional 25 Jesuits had tried to enter China, without success. But Ricci and one of his confrères prepared themselves very well, carefully studying the Chinese language and customs, and in the end, they managed to settle in the south of the country. It took 18 years, with four stages through four different cities, to arrive in Peking (Beijing), which was the centre. With perseverance and patience, inspired by unshakeable faith, Matteo Ricci was able to overcome difficulties and dangers, mistrust and opposition. Imagine those times: on foot or riding a horse, such distances… and he went on. But what was Matteo Ricci’s secret? By what road did his zeal drive him?

He always followed the way of dialogue and friendship with all the people he encountered, and this opened many doors to him for the proclamation of the Christian faith. His first work in Chinese was indeed the treatise, On Friendship, which had great resonance. To enter into Chinese culture and life, at first he dressed like the Buddhist bonzes, according to the customs of the country, but then he realised that the best way was to assume the lifestyle and robes of the literati — like the university professors and the intellectuals dressed — and he dressed the same way. He studied their classical texts in depth, so that he could present Christianity in positive dialogue with their Confucian wisdom and with the customs and traditions of Chinese society. And this is called an attitude of inculturation. This missionary was able to “inculturate” the Christian faith in dialogue, as the ancient fathers had done with Greek culture.

His excellent scientific knowledge stirred interest and admiration on the part of cultured men, starting from his famous map of the entire world as it was known at the time, with the different continents, which revealed to the Chinese for the first time a reality outside China that was far more extensive than they had thought. He showed them that the world was larger than China, and they understood, because they were intelligent. But Ricci and his missionary followers’ mathematical and astronomical knowledge also contributed to a fruitful encounter between the culture and science of the West and the East, which went on to experience one of its happiest times, characterized by dialogue and friendship. Indeed, Matteo Ricci’s work would never have been possible without the collaboration of his great Chinese friends, such as the famous “Doctor Paul” (Xu Guangqi) and “Doctor Leon” (Li Zhizao).

However, Ricci’s fame as a man of science should not obscure the deepest motivation behind all his efforts: namely, the proclamation of the Gospel. With scientific dialogue, with scientists, he went ahead, but he bore witness to his faith, to the Gospel. The credibility obtained through scientific dialogue gave him the authority to propose the truth of Christian faith and morality, of which he spoke in depth in his principal Chinese works, such as The true Meaning of the Lord of Heaven — as the book was called. In addition to doctrine, they are the witness of religious life, virtue and prayer: these missionaries prayed. They went to preach, they were active, they made political moves, all of that; but they prayed. It is what nourished the missionary life, a life of charity; they helped others, humbly, with total disinterest in honours and riches, which led many of his Chinese disciples and friends to embrace the Catholic faith. Because they saw a man who was so intelligent, so wise, so astute — in the good sense of the word — in getting things done, and so devout, that they said, “But what he preaches is true, because it is being said by a personality that witnesses, he bears witness to what he preaches with his own life”. This is the coherence of evangelizers. And this applies to all of us Christians who are evangelizers. We can recite the Creed by heart, we can say all the things we believe, but if our life is not consistent with this, it is of no use. What attracts people is the witness of consistency: we Christians must live as we say, and not pretend to live as Christians while living in a worldly way. Look at these great missionaries like Matteo Ricci who was Italian — looking at these great missionaries, you will see that the greatest strength is consistency: they were consistent.

In the last days of his life, to those who were closest to him and asked him how he felt, Matteo Ricci replied that he was thinking at that moment whether the joy and gladness he felt inwardly at the idea that he was close to his journey to go and savour God was greater than the sadness of leaving his companions of the whole mission that he loved so much, and the service that he could still do to God Our Lord in this mission (cf. S. De Ursis, Report on M. Ricci, Roman Historical Archive s.j. ). This is the same attitude of the Apostle Paul (cf. Phil 1:22-24), who wanted to go to the Lord, to find the Lord, but to stay “to serve you”.

Matteo Ricci died in Peking (Beijing) in 1610, at 57, a man who had given all his life for the mission. The missionary spirit of Matteo Ricci constitutes a relevant living model. His love for the Chinese people is a model; but the truly timely path is coherence of life, of the witness of his Christian belief. He took Christianity to China; he is great, yes, because he is a great scientist, he is great because he is courageous, he is great because he wrote many books — but above all, he is great because he was consistent in his vocation, consistent in his desire to follow Jesus Christ. Brothers and sisters, today, let each of us ask ourselves inwardly, “Am I consistent, or am I a bit ‘so-so’?”

Special Greetings

I extend a warm welcome to the English-speaking pilgrims and visitors taking part in today’s Audience, especially the groups from England, Malta, Indonesia, Malaysia and the United States of America. In a special way, I greet the many groups of university students. Upon you and your families I invoke the joy and peace of our Lord Jesus Christ. God bless you all!

Lastly as usual my thoughts turn to young people, to the sick, to the elderly and to newlyweds. Today, the last day of the month of May, the Church celebrates Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth, from whom she is proclaimed blessed for having believed in the Lord’s Word (cf. Lk 1:45). Look to her and implore her for the gift of an ever more courageous faith. Let us entrust to her maternal intercession, all those who are tried by war, especially dear and tormented Ukraine which is suffering greatly.

I offer my blessing to all of you.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti