TheHistory

Then there was

“I was in prison and you came to me”. These words from Matthew’s Gospel (Mt 25.36) summarize the meaning of a long lasting mission. With fluctuating effectiveness, but with determination, the Church has pursued an action devoted to meekness and mercy, well aware that prisons have been since Antiquity, terrible places where the accused were herded to await judgement; to live or die.

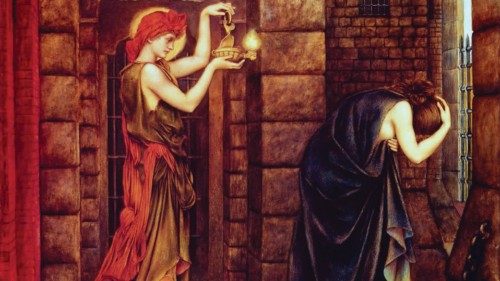

For a long time, in fact, the idea of prison as a place of reconciliation has remained distant. From the modern age onwards, and increasingly so, the Christian doctrine has tried to associate imprisonment with what - in the words of the French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep (one of the best known scholars of the 20th century) - we could describe as a rite of passage. In other words, imprisonment seen as an experience of purification experienced in a time and place of transition. Following the sentence’s completion, the penitent is refreshed, not least because of their inner exercise of dialogue and drawing themselves closer to God. A passage that is not so different from what one imagined one would do in the course of a pilgrimage; from what one imagined one would do in Purgatory; and, from what one would do during the course of one’s whole life.

Without being able to avoid harshness and atrocities, from the 16th-17th century the Church began to convey, through concrete examples, the image of prisons with dignity. In this sense, in 1655, straddling the pontificates of Innocent X and Alexander VII, a building was built in Rome that by its name signaled a revolution in the prison system. The Carcere Novo provided separate spaces for men and women, larger and cleaner rooms with a connection to the sewage system. The female prisoners were entrusted to the care of the Sisters of Providence and the Immaculate Conception. Going beyond the view that prison should be an enclave; this prison maintained a link with the city’s daily life and people, thanks to the activities of the confraternities, including that of the Pietà of Prisoners, the Assumption of Jesus and Saint John in Pigna. The local archconfraternity of St Jerome of Charity was to, among other things, “plead the causes of poor pupils and widows in the courts, endow spinsters, and distribute handouts especially to condemned women”. From that moment onwards, prisons built on the Roman model began to spring up almost everywhere throughout Europe. The English philanthropist John Howard, who was the first English prison reformer, made many journeys for study purposes to Italy while following the Grand Tour routes, and praised the Carcere Novo as he did so. He found it well kept, airy, equipped, and with scrupulous separation of men and women. In the 18th century, thanks to the reflections of the jurist Cesare Beccaria, who was one of the greatest exponents of the Italian Enlightenment, along with Howard himself, the awareness that there was no need to add afflictions to the deprivation of liberty increasingly ripened, even in Anglo-Saxon Countries. This reference is to the futility of forced labor; while repression gradually gave way to education. The pedagogical principle underlying the experience of imprisonment was to become a cornerstone of democratic states, when, in the age of the great Revolutions, first-generation rights were solemnly enshrined, i.e. those pertaining to individual freedom, freedom of thought, freedom of religion, the right to life, physical integrity and a fair trial.

In the contexts in which it has been able, the Church has consistently endeavored to fulfil her charitable mission by providing for the spiritual needs of prisoners, and more besides. The Church has done so before and after the importance of psychological care for prisoners’ wellbeing became apparent. That then, on a practical level, despite an attempt to persuade secular power to think alternatively too, prisons ended up being places of an exercise of power, of threat, of exclusion and isolation, this is a matter of historical and political order. In Surveillance and Punishment, the French sociologist Michel Foucault recalled that the prison as we understand it today has a relatively recent history, distinct, in this sense, from its pre-history. In mediaeval hospices, despite the provisions of the Corpus iuris civilis, orphans, the sick, the old, the poor and travelers ended up there. Those of the 16th-17th centuries were intended to take beggars off the streets, such as the General Hospice of the Poor founded by Innocent XII or, even earlier, the Hôpitals des Pauvres Enfermez, inaugurated after a ban on begging had been proclaimed in Paris in 1611. When women were found begging in the city streets, they were publicly whipped and shaved.

The French Benedictine, Jean Mabillon, known for being the founder of paleography and diplomatics (i.e. the sciences employed for studying documents from the past, while historically reconstructing the Church-ecclesiastical binomial), emphasized correctional practice. While secular justice is concerned with maintaining order, ecclesiastical justice must look after the salvation of souls, and inspire penitence. According to the ancient canonists, punishment was imposed to reconcile the offender with God.

Between noble intentions and the harsh reality, the distance remained, and was more often than not, unbridgeable. One of the priorities of the newly founded Kingdom of Italy was to reform and standardize the prison systems inherited from the pre-unitary states.

The Royal Decree on Penal Houses from 1862 highlighted an all-female peculiarity, which made the experience of female prisoners different from that of men. In both cases, the penal system was divided into three bodies: penal homes for those sentenced to more than two years’ imprisonment, judicial prisons for those with short sentences, and custodial homes for juveniles. However, unlike the men's prisons, which were run by the officials of the Prisons Directorate under the Ministry of the Interior, the penalty houses were entrusted to the care of the Sisters of St Vincent de Paul, the Sisters of the Providence of the Immaculate Conception and the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. The nuns who worked in the prisons depended, of course, on the Mother Superior, who was formally accountable to the prison director.

In 1890, though excluding the reformatories for girls, the religious orders administered fourteen institutions including Italian penal homes and judicial prisons. Even in the men’s penal homes, the tasks of maintaining and keeping the chapel, pharmacy, infirmary, kitchen and laundry in good order were entrusted to the nuns.

Although prisoners were by then guaranteed the right to freely profess their religion, for example by exempting Jews from all work on Saturdays or holidays, and non-Catholics in general from religious duties, including attending prayers and services, and even, if possible, inviting a Protestant minister or rabbi “to discuss matters of his religion”, this was still a confessional State. This involved exhorting the inmates to participate in the spiritual activities promoted by the chaplain.

It was perhaps this image that attracted intense criticism from part of the secular world, which was not always exempt from ungenerosity. At the dawn of the 20th century, two journalists and writers in Italy, Zina Centa Tartarini and Maria Rygier, the former an educator and prison inspector, the latter involved in the social and political struggle at the dawn of Fascism, focused on the role played by nuns in Italian women’s penal homes. They commenced with examining specific cases, for example in Rome, Perugia, Turin, and others besides. Tartarini, who used the pseudonym “Rossana”, denounced, in the “Nuova Antologia” magazine the often-dilapidated conditions of the facilities, the absence of regular schools and libraries, but above all the humiliation inflicted on those who were forced to wear a colored cap as an indication of the seriousness of the sentence (black for life imprisonment!). Rygier’s article entitled Monasticism in Women's Prisons, published in 1909 in the weekly newspaper Il Grido del Popolo [People’s Cry], and focused on the religious personnel.

The mother superior of the penal home in Turin, who ended up under indictment, defended herself by saying, significantly, that her penal home “was doing well”. Rygier’s anticlericalism went beyond understandable premises when he associated prayers and genuflections with the “fanaticism of the nuns”. Even the Marquise Tartarini, however, could not refrain from praising the work of the nuns, who did well if properly trained. In 1909, for example, the inspector commission of the reformatory of the Buon Pastore in Rome expressed the feelings of most sincere admiration for the management of that institute.

By GIUSEPPE PERTA

Lecturer in Medieval History, University of Naples, Suor Orsola Benincasa

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti