The Story

Women have been key players in the spreading of Christianity in different cultures throughout the centuries of the Christian era. However, despite the crucial role played by women missionaries, the study of their contribution has long been neglected, even by historians. There are many reasons for this oblivion, for example: the habit of a historiography that until recently paid little or no attention to the history of women and “female Catholicism”, and to the objective difficulties in accessing the archives of women’s religious congregations with regard to modern and contemporary mission history. In recent decades, the international affirmation of feminist theology, the promotion of interdisciplinarity, the diffusion of gender studies and the inclusion of Christianity studies in global history have stimulated new research, publications and projects that have brought together scholars from different parts of the world, while favoring a transnational approach to the history of women’s missionary congregations.

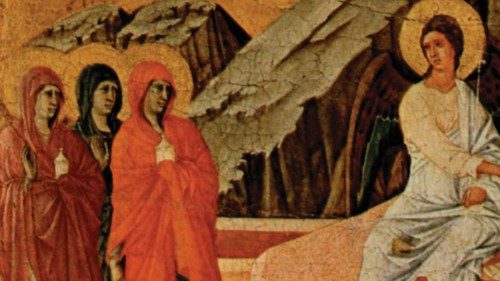

The first missionaries were found in the Gospels. John gives Mary Magdalene the mandate to witness and announce the death and resurrection of Jesus because in receiving the first apparition of the Risen One she becomes the first apostle of Christ. The evangelist Luke also entrusts Mary called the Magdalene, Joanna, Susanna and many other women who followed Jesus and the twelve with the missionary task of assisting them with their goods and sharing the Nazarene’s journey with them. At the origins of the Christian movement, the spread of the gospel was the work of itinerant missionaries, merchants and businessmen of a certain cultural and social level, as well as wealthy women. Pauline literature allows us to recognise the role of women missionaries who taught, preached, and founded house churches. Paul surrounded himself with collaborators and co-workers. To Phoebe he gave the title of diákonos, a missionary preacher in the church of Cenchrea; Priscilla and Junia are the women of Aquila and Andronicus with whom they form Judeo-Christian missionary pairs, a common missionary practice; the apostle Thecla received the task of teaching the word of God and became a missionary woman who preaches and baptizes from Paul. The female deacons of the Syriac Churches in the 3rd century who went into homes to visit and care for the sick are the example of early Christian charity, in this sense the earliest forms of the Church’s mission.

From the Late Antique period women were excluded from any form of ministry, so their activity was confined to prayer, asceticism and later to service and personal relationships as a way of witnessing the Gospel. In the early Middle Ages, women’s monasteries flourished throughout Europe, some of them led by particularly powerful abbesses. Lioba, an English Benedictine missionary nun, accompanied the Mainz bishop Boniface on his evangelising mission to Germany, and he made her abbess of Tauberbischofsheim. In the late Middle Ages we find figures such as the reformer of Lyons, Valdesius, who in his itinerant preaching inspired by the apostolic life of the origins did not exclude women, who in early Waldensianism were engaged in proselytising activities. While in the heretical movements women could also actively participate in the evangelising mission by preaching the Gospel in the streets and squares, instead, the the Inquisition condemned this freedom of women. In 1298, Boniface VIII forced religious women of all present and future orders and congregations into strict cloisters. This restriction prevented Clare of Assisi from following Francis but not from taking on the inheritance of his spirituality, giving rise to a feminisation of Christianity that was expressed in new forms of religious life linked to care and attention to the least. In the early 16th century, the Ursulines of Angela Merici embodied this new missionary spirit in the teaching and education of young girls. Henceforth, the way was opened for a mission to take place on the margins, beyond the centres of ecclesiastical power, as was later to become more evident in non-European territories.

In the modern age, the missionary zeal of the European Church was fostered by the possibility of Christianising populations subjugated by the major colonising powers. The Society of Jesus, with its special vow of obedience to the pope about missions, helped characterize mission as the evangelization of non-Christians. The Council of Trent reaffirmed cloisters for nuns and imposed residence in convents for religious women. Nevertheless, the missionary vocation of some of the numerous women’s congregations that sprang up between the 16th and 17th centuries did not diminish. The Ursuline nun Marie de l’Incarnation Guyart was the first missionary in Canada: she left in 1639 to join the Jesuits among the Huron Indians and in Quebec she built the first boarding school to teach the children of colonists and Amerindians. For European women, to become a missionary was also a way of escaping the social norms that forced them to have children in arranged marriages, while savoring an independence that was impossible in Europe, but meant taking the risk of long and often tormented journeys.

After the French Revolution, the missionaries of the new, mainly French women’s congregations reached North America to open schools for girls, establish hospitals, care for the sick and support immigrants. In 1807, Anne Marie Javouhey founded the Sisters of Saint-Joseph de Cluny, a missionary congregation that sent its women religious to Africa and French Guiana. In Italy, the first female missionary institute was the Combonian Institute of the Pious Mothers of Nigrizia (1872); this was followed by the founding of the Xaverian Sisters (1895), the Consolata Sisters (1910) and the Missionaries of the Immaculate (1936). In 1880, Francesca Cabrini founded the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Codogno, who dreamt of evangelising Asia. Leo XIII convinced her to head for the United States and in 1889, she settled in New York to help the vast multitude of Italian immigrants and orphans. As Mother Cabrini wrote, “The world is too small to limit ourselves to a single point. I want to embrace it entirely and reach out to all its parts”. Thus, the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart founded numerous missions in the United States, Europe, South America, Africa, Australia and China. In Asia, other French congregations embarked on missionary apostolates in Honk Kong, Indochina, Vietnam, Japan and the Philippines. In England, Elizabeth Hayes founded the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, and after moving to Rome in 1880, they established missions all over the world, serving as educators and working in hospitals.

Between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was an extraordinary migration of missionaries belonging to countless small and large congregations to all continents with a considerable impact in the educational, welfare and humanitarian fields in general. The female missionaries -and this is perhaps what distinguished them from their male counterparts-, established a direct, daily relationship with people, often with the most fragile such as women and children. They were cultural mediators in the process of adaptation of the proclamation and later of inculturation; for example, Salesians, Religious Teachers Venerin, Religious Teachers Filippini to name but a few. Freedom of movement meant acquiring autonomy and widening the margins of missionary intervention. In the 19th century, 400 women's congregations were created in France, a Country from which in 1901 more than 10,000 female religious left for the mission compared to 4,000 of their male counterparts. From the second half of the century from France, Italy and Germany some 590 mainly female congregations headed for the more urbanised and populous centres of Brazil such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The work of the women missionaries contributed to the cultural and social transformation of the populations they encountered, but not only in a positive sense. The missionaries still came from a world in which humanitarian and educational efforts were viewed as a work of civilization of peoples considered culturally less developed. As a consequence, the coercive and violent methods sometimes employed or practices such as maternage [mothering] in Eritrea to Italianize the population subjected to Italian rule had negative and in some cases devastating effects.

However, we also find nuns such as the German missionaries who made their anti-slavery contribution in Togo and New Guinea or the missionary doctors whose contribution was particularly important in countries where women could not be visited by male doctors. In 1925, the Austrian missionary doctor Anna Maria Dengel founded the Medical Mission Sisters, which became the first women’s congregation dedicated exclusively to medicine in 1935, after Propaganda Fide lifted the ban on sisters practicing this profession. From the second half of the 20th century, there was an increase in the demand for university preparation on the part of the missionaries. In the Middle East, after the establishment of the State of Israel and the creation of Palestinian refugee camps in neighboring countries, the missionaries who had been present in the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem since the previous century played an essential role in medical and nursing care.

Throughout history, the missionary action of women has therefore mainly taken place in the service of the marginalised, in the fields of education, care, medical assistance, and charity. This gave them the opportunity to approach people, to enter into the intimacy of their families, to win their trust, thus paving the way for the evangelization of male missionaries. This missionary strategy was also adopted in the Protestant world where we find many missionary couples, husband and wife, and many single women too. The China Inland Mission (CIM), founded in 1865, urged female missionaries to go into the inland provinces of China alone. In 1900, half of the 498 Protestant missionaries of the CIM were women. In 1861, Sarah Doremus founded the Women’s Union Missionary Society, an interdenominational Protestant missionary society that sent unmarried women on missions.

The Second Vatican Council changed the concept of mission, which was then taken up and further clarified in Paul VI’s post-conciliar apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975). Mission as proclamation and service in the name of Jesus was to concern the whole Church (people of God), men and women, priests and laity. Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium emphasized the need for an “outgoing” Church, where the dimension of care and dialogue with the other is central. Missionaries are therefore still called to play a decisive role that must be recognised.

by Raffaella Perin

Catholic University of the Sacred Heart

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti