History

Living Heritage refers to that living cultural heritage, be it material or immaterial, while being generally linked to a place, which is preserved, handed down, enriched through the work of a community. The most immediate example, in cultural heritage of religious interest, is monasteries. There lay a heritage, today and for the last two centuries, and increasingly, at risk, because secularization, of religious houses in primis, and of society at large, with the consequent decline in vocations, has often caused a break in tradition. In many cases all that remains are ruins or mere titles. Nevertheless, is it possible to perpetuate the spirit of the sacred space after the abandonment of the place by the community that generated it, if it has acquired, over time, different functions from the initial ones? The reuse of buildings for purposes other than the original ones is, of course, an ancient tradition. However, the adaptive reuse combined with the awareness of their historical value is quite recent and has been theorized in several UNESCO documents, while deserving the attention of the Pontifical Council for Culture too, which dedicated significant reflections to the afterlife of religious houses in the context of the international congress Charisma & Creativity, held at the Pontifical Antonianum University.

The Suor Orsola Benincasa, the oldest free university in Italy, is a model in this respect. It was founded in 1885 in Naples, on the slopes of Mount Sant’Elmo, in the place that the venerable Orsola, a Neapolitan mystic who lived between the second half of the 16th and the first quarter of the 16th century, had chosen as a refuge and the seat of a congregation of oblate nuns.

Hagiographic tradition has it that Orsola was born in Cetara, a seaside village on the Amalfi Coast, from where the family is said to have emigrated to escape the raids of the corsair Barbarossa. The same memory connects her, by descent, to another Benincasa, Catherine of Siena, who provided the model to which the biographers certainly looked, in a spirit of imitatio, but also, perhaps, the young Neapolitan girl, precociously enraptured by frequent and prolonged ecstatic experiences, accompanied by prayers, privations and premonitions. In the age of the Counter-Reformation, Orsola could not escape the scrutiny of the Inquisition, not least because of the clamour that such phenomena began to arouse in Neapolitan society and in Rome, even though Filippo Neri, appointed by the pontiff as the principal examiner of the case, judged her to be honest and pure after rigorous examinations.

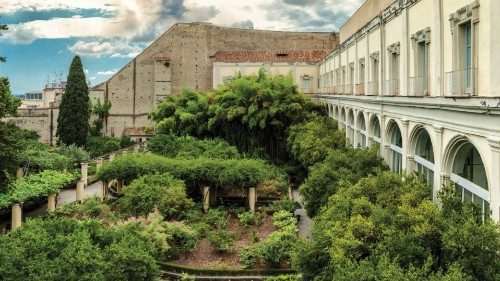

The hermitage where Orsola had taken refuge with some relatives and sisters, twinned around a small house with an adjoining kitchen garden, was enriched by the Church of the Immaculate Conception, still hoisted at the top of the university citadel. The congregation, which after the foundress’ death saw the establishment of a cloistered monastery affiliated to the Theatine Order, dedicated itself to the education of girls from its outset. This element constituted, in fact, the founding charisma, as well as the identity code, of a centuries-old history, characterised by a life experience handed down, from generation to generation, from teachers to disciples. With its gardens and its cloister, the syllable of the little doors and the climbing of the stairs, it offered the scenario of the locus amoenus, isolated and exalted at the same time, a prefiguration of Paradise.

The new history of Sister Orsola, which began in the second half of the 19th century with the unification of Italy, when the creation of an educandato managed to circumvent the royal decree of 1867, by which all ecclesiastical institutions were suppressed, which would otherwise have led to the state confiscating their property. This era is marked by a succession of female figures who devoted themselves, without interruption, to the ideal of the redemption of women, through education, from a condition of objective subordination; it was a society in which study itself and leadership roles were considered the prerogative of men.

At the end of the 19th century, stresses the current rector of the University Lucio d'Alessandro, “the monastic citadel was transformed into a citadel of knowledge”, once again in the sign of a woman; “If Orsola is the founder of the place, Adelaide del Balzo re-founded it”.

Adelaide del Balzo married the Neapolitan nobleman and prince of Strongoli Francesco Pignatelli, while as lady-in-waiting to the first queen of Italy Margherita of Savoy, she was appointed inspector and then governor of the Sister Orsola Institute in 1891.

The princess was able to set up a long-lasting project, based - as Vittoria Fiorelli, professor of Modern History at the Sister Orsola Benincasa, points out - on the Leitidee, the guiding idea, to give shape to “a more conscious female presence on the scene of the nation”. The project took the form of two courses of study, one with a humanistic orientation, and one in home economics and manual labour. The latter should be viewed in the context of another initiative desired by Princess Pignatelli, the establishment of the Croce Azzurra, a specialist school for the paramedical professions that relied on the Neapolitan Gesù e Maria Hospital for its practical activities, while maintaining the theoretical lessons at Sister Orsola.

Adelaide del Balzo wanted the pedagogist Maria Antonietta Pagliara, the first suffragette and the first woman in Italy to head a higher institute, to be her headmistress. She brought the most advanced European pedagogical experiences to the Faculty of Education, aimed at revolutionizing the training of teachers, even before the students. For their girls, the princess and the headmistress dreamed of the activities of workers, a culture of literate women, and the manners of princesses. The “plan of action” was avant-garde, because it was avowedly oriented not only towards modernizing the elites but also towards spreading culture to the less well-off classes. Pagliara’s appointment had come at the culmination of an important year, 1901, which sealed the triumph of the Sister Orsola model, where King Umberto I and Queen Margherita had arrived the year before on an official visit.

During the 20th century, many Neapolitan women, who were leading figures in pedagogy, philosophy and literature, moved in the footsteps they had traced, whether that be the philosopher of education Cecilia Motzo di Accadia, to the writer and environmentalist Elena Croce, to the pedagogist Elisa Frauenfelder. The women’s bequest was also of a material nature, comprising land and buildings that guaranteed a certain amount of autonomy, as well as an artistic heritage that, from the time of Sister Orsola to the present day, has handed over to the Athenaeum. To the care of the young people who train there, assets of great value such as the historic gardens of the Claustro and the Cinque Continenti, the archival and book collections of the Pagliara Foundation and the Capocelli Library, the Museum of the University Opera and the Sala degli Angeli, formerly a cloistered church, now used as a lecture hall, and thus the highest expression of the transmission of knowledge that looks to the future, without forgetting the past.

As an institution, the Sister Orsola owes its survival to adaptation to sustainable uses. It is no coincidence that, alongside courses characterizing the long-standing pedagogical mission, such as those pertaining to the department of educational sciences, the university has promoted other avant-garde ones too. These include those of green economy and digital humanities, also to enhance its heritage in the light of contemporary challenges. The link with material and moral heritage has continually reshaped itself, adapting to a new dimension, and to a 'society in revolution'.

by GIUSEPPE PERTA

Lecturer in Medieval History, University of Naples Suor Orsola Benincasa

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti