More than three decades ago, in the Fall of 1988, I started helping as a volunteer at the noon meal of the Good News Soup Kitchen on West Georgia Street in Tallahassee, Florida. My penthouse law office on the 8th Floor of a downtown office building was only five blocks from the inner-city soup kitchen. But that short walk took me from some of the priciest real estate in town to the heart of the ghetto — a totally different world. I showed up every day from 11:00 a.m. until 1:30 p.m. on foot, in my three-piece lawyer-suit and Countess Mara silk tie to help serve the midday meal to the street people.

The well-seasoned kitchen staff assigned me to door duty — a menial task that always fell to the newest volunteer. My responsibility was to ensure that the street people lining up to eat waited in line outside the backdoor in an orderly fashion. Every day, I stood at the backdoor of the soup kitchen for over an hour, chatting with the street people waiting to eat.

Before I came to volunteer at Good News Ministries, street people was a meaningless term that defined a group without defining anybody in particular. From the comfort of my car, my suburban home and my downtown law office, street people were just those people out there somewhere. None of them were important enough for me to know their name, their story, or the details of their life.

Then, one day while I was on door duty, an elderly woman named Helen came running to the Good News door. A man was chasing her threatening to kill her if she didn’t give him back his dollar.

“Tell him he can’t hit me here ‘cuz it’s church property!” she pleaded to me.

In true lawyer fashion, I explained that Good News Ministries is not officially a church, but he still could not hit Helen. My eloquent distinctions between a church and a nonprofit ministry were of no interest to anyone within earshot. After twenty minutes of failed mediation, I purchased peace by giving each of them a dollar.

That evening, I happened to be standing on the corner of Park Avenue and Monroe Street, in front of my office building, enjoying a beautiful Tallahassee sunset. In the chill of the red-twinged twilight, I spied a lonely silhouette struggling in my direction from Tennessee Street.

“Poor street person,” I thought, as the figure inched closer.

I was about to turn back to my own concerns when I detected something familiar in that shadowy figure. The red scarf. The clear plastic bag with white border. The unmatched shoes.

“My God,” I said in my thoughts, “that is Helen.”

My eyes froze on her as she limped by and turned up Park Avenue. No doubt she would crawl under a bush to spend the night. My mind had always dismissed the sight of a street person in seconds. But it could not expel the picture of Helen.

That night, as I lay on my $1500 deluxe, temperature-controlled waterbed in my affluent suburban home, I could not sleep. A voice in my soul kept asking, “Where’s Helen sleeping tonight?”

No street person standing outside my law office building had ever interfered with my sleep. But the shadowy figure with the red scarf and plastic bag had followed me home. I had made a fatal mistake. I had learned her name.

Two decades later, it’s a Saturday morning in Winter Haven, Florida. The 10:00 a.m. sun pours from a cloudless sky over the citrus trees behind the church. Orange specks peer brightly from among the bright green leaves. The sloping roof of St. Matthew’s Catholic Church answers in its own hues of deep green. All a beautiful backdrop for the unusual event unfolding in the portico of the church.

The rear door of the shiny black hearse swings open. Six pallbearers receive the casket. A crowd of about seventy parishioners is present to partake in the solemn funeral Mass that acknowledges this deceased as one of us, a Catholic brother in Christ. What is unusual is that none of these people is related by blood to the man who has died. Almost none of them have ever met him face-to-face. Yet, here they are, and here is his body.

A white cross-bearing cloth is draped over the coffin. The pastor, Father Ruse, begins a blessing and leads the procession inside. The simple brown-varnished box containing the remains is positioned in front of the altar and astride the towering beauty of a white Easter Candle. All the symbols proclaim life. The Mass begins.

Ricky, the deceased, was executed at 9:30 a.m. Wednesday October 2, 2002 by lethal injection at Florida State Prison. Father Ruse was his spiritual advisor. After four years of monthly visits and five weeks of deathwatch weekly visits, Father Ruse was with him at cell front for the five hours prior to execution. My wife and I served as a support for Father and the members of his pastoral team who participated in the vigil and prayers that surrounded this event. Father never came alone to Florida State Prison. In a very real sense, all these people from his parish who are gathered here today came with him.

This is a piece of the mystery of church. This is the family of faith, a visible sign of the Community of Saints. I’ve heard it said that the Eskimo language has no word for orphan because any child who loses its parents is immediately absorbed into another family. There are no orphans. This Catholic Family of Faith is the same reality in the spiritual realm. There are no abandoned members of this family. No one from this family should ever end up in Boot Hill.

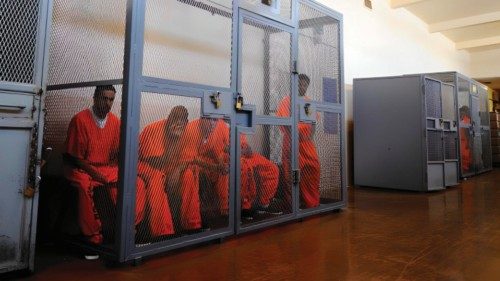

Boot Hill is the ultimate statement that a human life did not matter to anyone. It is the ultimate degradation for those who have already been relegated to the bottom of the pile. Boot Hill is the state administered pauper’s graveyard for those who die in prison at Raiford or Starke with no one to even claim their body. I’ve been told that men’s bodies have been removed from the execution chamber, processed by the medical examiner and sent directly to Boot Hill. There is no more effective pronouncement that a human life mattered to no one.

These good people of St. Matthew’s of Winter Haven are taking a stand this morning for the value of human life, not just in general, but in the particular case of this man who some considered to be valueless. They are taking this stand at the cost of their personal resources of time, mind and money. They are throwing down the gauntlet in the face of the culture of death, choosing to see this man not as his worst deeds, but rather as God sees him, made in the image and likeness of God.

Through the course of the funeral Mass prayers are offered for his victims, their loved ones and for him and his loved ones. Some of the songs sung are the same as those that Ricky and Father Ruse sang with the prison chaplains at his cell front just hours before his death. Ricky’s final words are shared. In closing the homily, Father Ruse says, “This is church at its best.”

Now, it is the Fall of 2022. It has been more than three decades since I witnessed Helen’s evening struggle up Park Avenue. Since that time, the changes in my life have allowed us to learn the names and stories of tens of thousands of people who have blessed us with their faith and courage. We have been changed by knowing them. We dare not forget them.

Recently, Fr. Ruse made a profound remembrance on October 2nd, Feast of the Guardian Angels, marking the 20th year since the State of Florida executed Rigoberto “Ricky” Sanchez-Velasco at Florida State Prison in Starke, Florida, writing:

“He was my friend. I sat with him in those last hours, in that very last minute. My ministry to him as priest and friend confirmed the mystery of God’s working among us and loving us, all of us, no matter our choices. This remembrance still feels the tragic loss of life of his victims, and the suffering among their families. Ricky’s family is also remembered.

“Gratefully the conversation about the death penalty, mental illness, fear and violence, the unequal and arbitrary justice for the poor and the other, the emotional, reactionary and privileged administration of law and justice, a broken penal system, among many other human and soul concerns, still occupies and unsettles society.

“May his soul, and the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace. Amen.”

Thank you, Helen. Thank you, Ricky. Thank you, Fr. Ruse.

You have all blessed us abundantly.

By Dale S. Recinella

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti