History

Clare and her vow

Despite the fact that it is commonly held that Gregory the Great had already passed on to the Middle Ages the ideal of equality of Ciceronian matrix (Omnes namque homines aequales natura sumus), in fact it was not - and is not - so. There were rich and there were poor, with the aggravating circumstance that in that age of sharp contrasts, of dazzling lights and deep shadows, the gap between wealth and poverty was very wide. For the poor, the winter was terribly harsh and the summer sultry; for the rich, the canteens were abundant with succulent produce, the beds soft and safer. One was equal, in short, only before God.

The choice of poverty was - and is, but at the time it was even more so then– a radical decision, especially for a woman like Clare of Assisi (1194-1253), who lived at that time. This was a “masculine” age it is written, not because it was difficult for female figures to emerge, for there are those who were endowed with determination, power, command, possibilities and means (for example, the Longobard Theodolinda to Isabella of Castile, passing through Matilda of Canossa) but because their capacity to make choices about their own lives were in some way conditioned, hindered, fought against more vehemently by those who believed they could limit the enjoyment of what today we would call social and civil rights.

According to her biographer, Thomas of Celano, when Clare’s father, Favarone, heard of Clare’s decision to devote himself to the ideal of life that had already seduced St Francis, he, who was a member of the ancient nobility of Assisi - the family home stood in Piazza San Rufino, in the centre of the village - reacted harshly. He lacked neither the force of violence nor the venom of promises that could induce his daughter to renounce her decision. He considered the choice inappropriate for a woman of that rank. On the other hand, Clare had not just overturned her father’s plans for a secure marriage, aimed at the economic and social consolidation of the family, but presented herself at the monastery of San Paolo deliberately without a dowry. If she did so, she was destined not to the duties of a choir nun, but to the humble occupations of a servant. For a while, Clare was forced, to wander about; however, in the end, it was her relatives who desisted, seeing her so obstinately clinging to the altar habit, to the steadfastness of her faith and to the decision, now made, to become a penitent forever. The choice had been marked, symbolically, by the cutting of her hair so short.

Clare had certainly followed the example of Francis, whom she had known, met, and listened to. In the beginning, the sisters who gathered at San Damiano had no other Rule than the instructions given by Francis. Nevertheless, Clare’s adventure had all-female peculiarities. The foundress of the Poor Clares molded a new Rule, the first to be written by a woman (with the intervention of Cardinal Ugolino, it is true, the future Gregory XI) and designed specifically for women nuns, who until then had had to adapt texts and customs that had been interpreted in the male fashion. An element that can be associated with a kind of emancipation emerges with absolute clarity in this Rule. The foundress leaves the “poor recluses” a certain freedom in the management of their property, both that which they owned before monasticism and that obtained in inheritance. Clare thus manifested full trust in her sisters, whose decision had nothing to do with constraint; it was a choice of devotion and pursuit of evangelical ideals; it was love for poverty. There was no reason, from this perspective, to impose privations, fasts, or penances. Poverty thus became a “privilege”, and as such was recognised by Innocent IV in 1253, shortly before Clare’s death. In essence, it defended the Poor Clare’s right not to receive lands and possessions of any kind. All the pope’s efforts to mitigate the harshness of the vow of poverty through the concession of certain properties were in vain, since property, as Paul Sabadier has written, was, for them, “a cage with gilded girdles, to which the poor larks are sometimes so well accustomed, that they no longer think of escaping to fling themselves into the midst of heaven”. Therefore, the innovation of Francis and Clare’s message lay in understanding this poverty in a broad sense, not as a renunciation, but as a vow of freedom. Indeed, unlike Francis, who had all of a sudden put aside the debauchery of his youth to marry Our Lady Poverty, she had distinguished herself since childhood in seeking to alleviate the suffering of the needy. The testimonies collected during her canonisation process give us pause to recall how, as a young girl, within the walls of a wealthy and noble residence, she was preoccupied with setting aside food for the poor.

Clare’s experience is innovative, but not singular. Umbria is the homeland of many saints, for example, Scholastica of Norcia, sister of Benedict, and Rita of Cascia. In addition, together with Clare, her mother, her sisters, and friends followed in the footsteps of Christ. The first, Ortolana, had been a pilgrim in the Holy Land. The latter’s daughters, Agnes and Beatrice, followed Clare to the convent. Then there is the childhood friend, Pacifica di Guelfuccio, who was the first, together with Clare, to flee from the palace at nightfall. Nor should one forget St Agnes of Prague, abbess and daughter of a king, with whom Clare kept up an epistolary correspondence. Therefore, all the sisters in Europe, from the 1330s onwards, replicated the experience of San Damiano; in Italy alone, at the foundress’ death, more than a thousand Poor Clares are documented throughout sixty-six convents. Could one, then, not remember the most recent, lamented biographer? Chiara Frugoni knew in her youth, from her own personal experience, the signs of austerity, privations, and penance. Not even the pen of Dacia Maraini has been able to resist the Clarian fascination, who, recounted her through a dialogue with an imaginative and passionate reader - at times, in truth, mockingly - imagines her as strong-willed, disobedient, and revolutionary.

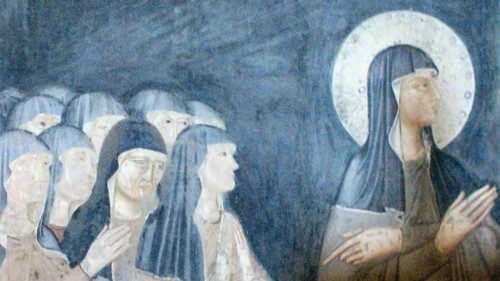

The hagiographic and canonisation process, which was rather singular, was so rapid that it prompted Jacques Dalarun, one of her most distinguished scholars, to speak of the “making of a saint”. Thomas of Celano organised his hagiographic dossier while Clare was still alive. In fact, we read of her qualities in the First Life of Francis (1228): “clear by name, clearer by life, most clear by virtue”. As such, Giotto depicted her at the end of the 14th century in the frescoes of the Upper Basilica with a halo, inspired by the Legenda Maior by Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. This being so, it is not difficult to understand why, just two months after her death, the bishop of Spoleto was commissioned by the pontiff to institute the canonisation process that would lead, in 1255, to the bull Clara claris praeclara meritis. Alexander IV and his chancellery emphasized - with some play on words and not too sophisticated rhetorical devices - the splendour and claritas of an experience lived, in reality, very intimately, as a poor recluse, amid prayers and silence. Splendour and luster did not always project her out of Francis’ shadow. It was the Middle Ages, however, masculine; but amidst the shadows, light was able to make its way through.

By GIUSEPPE PERTA

Lecturer in Medieval History, University of Naples Sister Orsola Benincasa

Chiara, the film

The revolutionary act of Saint Clare, who stripped herself of her nobility and chose poverty, is recounted in the film Chiara [Clare], directed by Susanna Nicchiarelli. The film, starring Margherita Mazzucco, in her film debut, was included in the 79th Venice Film Festival, where it received several awards; for example, the Sorriso Diverso Venezia Award, assigned to works of social interest that value diversity and protect people’s fragility; the Carlo Lizzani Award assigned by a jury of exhibitors; and the Signis Award promoted by the World Catholic Communication Association Signis (Credits Emanuela Scarpa 2022 Vivo film, Tarantula).

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti