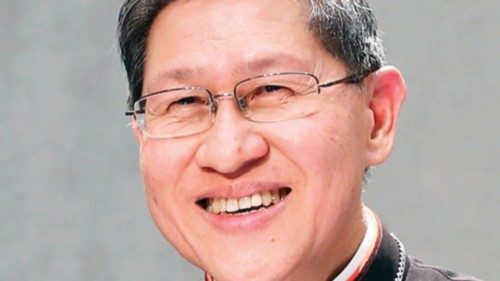

Cardinal Luis Antonio Gokim Tagle uses calm tones and carefully measured words to explain the reasons for the Holy See’s decision to extend for two more years the Provisional Agreement with China on the appointment of Bishops, signed in September 2018 and renewed on 22 October 2022. “The reason for everything is to safeguard the valid apostolic succession and the sacramental nature of the Catholic Church in China,” says the Filipino Cardinal, adding, “this can reassure, comfort and enliven baptized Catholics in China”.

What are the criteria that led the Holy See to persevere in the decision taken four years ago?

The agreement between the Holy See and the Chinese government signed in 2018 concerns the procedures for choosing and appointing Chinese bishops. This is a specific issue, which touches a crucial point in the life of the Catholic community in China. In that Country, historical events had led to painful wounds within the Church, to the point of casting a shadow of suspicion on the sacramental life itself. So there were things at stake that touch the intimate nature of the Church and her mission of salvation.

With the Agreement, attempts are made to ensure that Chinese Catholic bishops can exercise their episcopal task in full communion with the Pope. The reason for everything is to safeguard the valid apostolic succession and the sacramental nature of the Catholic Church in China. And this can reassure, comfort and enliven baptized Catholics in China.

The Holy See has always reiterated the circumscribed nature of the Agreement, which also touches a vital issue for the Church and for this reason too, it cannot be reduced to a side element of some diplomatic strategy. Any consideration that ignores or obscures this singular physiognomy of the Agreement, ends up giving it a false representation.

It is not yet time to take stock, not even provisional ones. But from Your point of view, how do you see the progress made and the effects of the Agreement?

Since September 2018, six bishops have been ordained, who were appointed according to the procedures set out in the Agreement. The channels and spaces for dialogue remain open, and this is already relevant in itself, in the given situation. The Holy See, listening to the Chinese government and also to bishops, priests, religious and laity, becomes more aware of this reality, where fidelity to the Pope has been preserved even in difficult times and contexts, as an intrinsic datum of ecclesial communion. Listening to the arguments and objections of the government also leads us to take into account the contexts and the “mindset” of our interlocutors. We discover that things that are absolutely clear and almost obvious to us can be new and unknown to them. For us this also represents a challenge to find new words, new persuasive and familiar examples for their sensitivity, to help them understand more easily what we really care about.

And what does the Holy See truly have at heart?

The intent of the Holy See is only to favor the choice of good Chinese Catholic bishops, who are worthy and suitable to serve their people. But favoring choices of worthy and suitable bishops is also in the interest of national governments and authorities, including Chinese ones. Then, one of the wishes of the Holy See has always been to foster reconciliation, and to see the lacerations and contrasts opened within the Church by the tribulations it has gone through, healed. Certain wounds need time and God’s consolation in order to be healed.

Isn’t there a risk of hiding the problems under the veil of a priori optimism?

Since this process began, no one has ever shown naive triumphalisms. The Holy See has never spoken of the agreement as the solution of all problems. It has always been perceived and affirmed that the path is long, it can be tiring, and that the agreement itself could cause misunderstandings and disorientation. The Holy See does not ignore and does not even minimize the differences of reactions among Chinese Catholics in the face of the agreement, where the joy of many is intertwined with the perplexities of others. It is part of the process. But one always has to dirty one’s hands with the reality of things as they are. Many signs attest that many Chinese Catholics have grasped the inspiration followed by the Holy See in the ongoing process. They are grateful and comforted for a process that confirms before all their full communion with the Pope and the universal Church.

Civil authorities intervene in the choice of Chinese bishops. But this does not seem new or exclusive to the Chinese situation...

The intervention of civil authorities in the choices of the bishops has manifested itself several times and in various forms throughout history. Even in the Philippines, my Country, the rules of the “Patronato Real” were in force for a long time, with which the organization of the Church was subjected to the Spanish royal power. Even St. Francis Xavier and the Jesuits conducted their mission in India under the patronage of the Portuguese Crown... These are certainly different things and contexts, since each case has its specificity and its historical explanation. But in such situations, the important thing is that the procedure used for episcopal appointments guarantees and safeguards what the doctrine and discipline of the Church recognize as essential to live the hierarchical communion between the Successor of Peter and the other Bishops, successors of the Apostles. And this also happens in the procedures currently used in China.

The Chinese government always calls the local Church to the demands of “Sinicization”...

Throughout history, Christianity has always lived the processes of inculturation also as an adaptation to cultural and political contexts. The challenge also in China may be to attest that belonging to the Church does not represent an obstacle to being a good Chinese citizen. There is no contradiction, there is no either-or, and indeed the apostles’ walking in the faith can help make good Christians also good citizens.

At this stage of the process, and in the face of possible slowness and setbacks, what can the Holy See rely on? What can one trust?

The sensus fidei witnessed by so many Chinese Catholics is always comforting. A precious testimony, which often sprouted not in well-cultivated and protected gardens, but on harsh and uneven grounds. If I look at the history of Catholicism in China in recent decades, the passage of St. Paul in the Letter to the Romans always comes to mind: “What will separate us from the love of Christ? Will anguish, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or the sword? No, in all these things we conquer overwhelmingly through him who loved us”. Many Chinese Catholics have experienced what St. Paul writes. The tribulations, the anguish, but also the victory given by Christ’s love for them.

What answer is to be given to those who say that the Holy See, in order to deal with the Chinese government, hides and ignores the sufferings and problems of Chinese Catholics?

Past and even recent sufferings and difficulties are always before the Apostolic See’s gaze on the events of the Church in China. Even the present choices are made precisely starting from this recognition and gratitude for those who have confessed their faith in Christ in times of tribulation. In dialogue, the Holy See has its own respectful style of communicating with representatives of the Chinese government, but which never ignores and indeed always makes present the situations of suffering of Catholic communities, which sometimes arise from inappropriate pressures and interference.

What can favor the recognition of the so-called “underground” bishops by the Chinese political apparatus?

This is a point always considered in the dialogue. To favor the solution of this problem, perhaps it would be useful to keep in mind by all that bishops cannot be seen as “officials or functionaries”: bishops are not “functionaries of the Pope” or “of the Vatican”, because they are the successors of the Apostles; and they cannot even be considered as “religious officials” of worldly political apparatuses, or as Pope Francis says, “State clerics”.

The confusion regarding the episcopal ministry and the relationship between bishops and the Pope does not seem to exist only in China...

Once I heard a tour guide in St. Peter’s who tried to explain to tourists the figure and role of the Pope in the Church, trying to find images that were familiar to them: “the Church”, said the guide — “is like a large company, like Toyota or Apple. And the Pope is like the executive director of this ‘company’”. Tourists seemed satisfied with this explanation, and surely returned home with this idea — not exactly in accordance with the true role — of the Pope as CEO and of the Church as an economic and financial enterprise...

You, called to Rome by Pope Francis as Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples — what impression do you have of the forms and energy with which Chinese Catholics live their missionary vocation even towards the multitudes of compatriots who do not know Jesus?

I see that parishes and communities carry out pastoral and charitable work with fervor and creativity throughout China. Every year there are many new baptisms even among adults. It is an apostolic work carried out by Chinese Catholic communities on a daily basis, always in harmony with the suggestions of the papal magisterium, even within many limits. In recent years, Chinese Catholic communities have lived the Year of Faith, the Jubilee of Mercy and many charitable initiatives during Covid, intensely. Even when I lived in Manila, I was always struck by the testimony of Chinese Catholics and other communities from nations where they live in minority conditions and also in difficult contexts. Expatriate Chinese Catholics also continue to help the Church in China in many ways, for example by supporting the construction of churches and chapels. Local Churches have geographical borders, but there is a human space of ecclesial communion that transcends borders.

What memory does your mother have of the faith of her Chinese ancestors?

My mother was born in the Philippines, and she grew up in a Filipino rather than a Chinese context. My maternal grandfather had become a Christian and received baptism. He was a very concrete and “pragmatic” Chinese Catholic. On the anniversary of his mother’s death, he offered incense and food in front of the image of his mother, and said to us grandchildren: “Nobody must touch this food! First the great-grandmother must taste it, in heaven, and then it is our turn...”. His memory, in a certain way, now also helps me to consider what can be more useful in the dialogue with the Chinese government.

What are you referring to?

When I confided to my grandfather my desire to enter the seminary, he told me: “I did not imagine that my grandson would become a priest… I do not understand this world of priests!”. I felt a little mortified, and then he added: “I do not understand, but I still want you to be a good priest”. Now, when I consider the dialogue with the Chinese government on ecclesial issues, I think that sometimes it is better to look for simple and direct arguments, to meet the concrete and pragmatic approach of our interlocutors. They cannot be expected to grasp the mystery of the Church in depth, vivified by the Holy Spirit. It was also difficult for me to explain to my grandfather the source of my priestly vocation… And it was important for me to take into account even his simple desire that I be a good priest.

Gianni Valente

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti