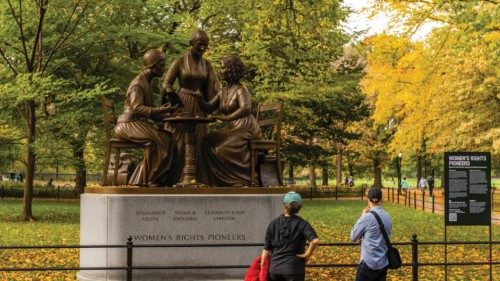

One hundred years. It took this long, after the introduction of universal suffrage in America, to dedicate a monument to the feminist pioneers who made this epochal milestone possible. There names are: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth. Since 2020, the three suffragettes, portrayed by sculptor Meredith Bergmann, have been giants on the Literally Walk in Central Park, the green heart of New York. With its 42 million annual visitors, it is one of the most visited places in the world. There are other monuments in the park, for example Shakespeare’s Juliet and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, but their’s is the only monument dedicated to non-fictional characters. The majestic bronze work celebrates the three activists who, animated by a prophetic vision of society based on equal rights between the sexes, dedicated their lives to changing the condition of women in the name of emancipation as early as the 19th century. Challenging the patriarchal mentality and laws of the time through writings, speeches, travel, petitions, associations, collective struggles and provocative actions.

Who were Susan, Elizabeth and Sojourner, these three women of different backgrounds and education yet united by their civic commitment and proto-feminist struggles? Susan Bromwell Anthony (15 February 1820-13 March 1906) was born into an open and progressive family, of the Quaker religion, which even when a child was encouraged to cultivate her lively intelligence, to study, and be independent. It was her father, with his teaching at home, who filled the gaps in the school education, which had been designed to favour boys. However, it was her teacher, Mary Perkins, who introduced the future suffragette to the commitment to women’s equality and who transmitted to her a progressive conception of the female condition. In 1840, Susan became a teacher and activist in her own right. Her first battle was for equal pay, which was unthinkable at the time.

In 1848, she signed the Declaration of Sentiments, presented at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first organized by women including Elizabeth Cady Stanton (with whom she founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869) and the founding act of the suffragist movement in America. Susan broadened her commitment to the anti-slavery cause, fighting against alcoholism and segregationist policies and behaviour. In the weekly newspaper The Revolution, she published her calling cry, “The True Republic: men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less”. On November 5, 1872, she had herself and 14 female companions arrested for breaking the law by voting in the presidential election. In court, she defended herself thus: “These are laws made by men, interpreted by men and administered by men in favour of men and against women”. To the judge who asked her if she voted as a woman, she replied, “No, as a citizen of the United States”, and refused to pay the $100 fine.

She died in 1906, 14 years before universal suffrage was introduced into the Constitution through an amendment that was named after her. Susan was the first woman depicted on one-dollar coins. In 1995, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano included her in a book dedicated to female figures who fought in the name of freedom against the established power.

Civil commitment, women's equality even in the religious sphere, birth control, equal rights in marriage, the fight against slavery. These were the causes of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (12 November 1815 - 26 October 1902), the daughter of a Federalist lawyer, congresswoman and Supreme Court judge, who tied her name to many battles for equality. First, that for women’s right to vote as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, a position she later left to her friend Susan B. Anthony to be free to travel and support the cause.

Between 1895 and 1898 Elizabeth was one of the 26 women scholars, of The Woman’s Bible, a feminist reinterpretation of the Holy Scriptures. The publication provoked bitter controversy for its radical positions, including the belief that the Holy Trinity was composed of “a heavenly Father, Mother and Son”. In 1840, Elizabeth married abolitionist lecturer Harry Stanton and, in the name of an equal relationship, refused to take the traditional vow of obedience to her husband and give up her own surname, which she added to the man’s instead. The couple had seven children, the last four born under a programme that the suffragette called “voluntary motherhood” and based on her full control of intimate relationships.

In 1848, at the Seneca Falls conference, Cady Stanton drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, a manifesto of equality. She took a stand for egalitarian divorce laws; supported a wife’s right to reject her husband’s sexual advances; the recognition of women’s property and labor; and, interracial unions. She died eighteen years before the introduction of women’s suffrage, a subject to which she had devoted three volumes in the last years of her life.

The African-American, slave-born Isabelle Baumfree (date of birth uncertain, c. 1797 - 26 November 1883) was the suffragette who, at the age of 46, decided to call herself Sojourner Truth and, although illiterate, dedicated her life to the abolition of slavery. Her’s was a very hard life, as recounted in the autobiography she dictated to a friend. She was sold at auction at the age of nine -together with a flock of sheep- for barely a hundred dollars, then beaten and raped by her master, resold twice more, she was forced to marry an older slave by whom she had five children. In 1827, following the abolition of slavery, the master promised her freedom. Nevertheless, he went back on his word so the woman decided to run away with her youngest daughter Sophia, leaving the other children who, according to the law, would not be emancipated until their twenties. She worked as a maid in a liberal family and when she learnt that her five years old son, Peter had been sold illegally, she appealed in court and got the child back. Until that date, Isabelle Baumfree was the first woman in history to take a white man to court, and win the case.

Having become a Methodist, she changed her name in 1843 and began travelling around America preaching against slavery, segregationism, capital punishment and for women’s rights, religious tolerance and pacifism. In 1851, she delivered her famous speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” which was a vibrant hymn to equality. In 1858, someone interrupted one of her lectures accusing her of being a man. Sojourner responded by opening her blouse to show her breasts. In 1864, she met President Abraham Lincoln. She died in 1883, when the vote for women was still a utopia; however, her passion, generosity and pain helped make it a reality thirty-seven years later.

By Gloria Satta

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti