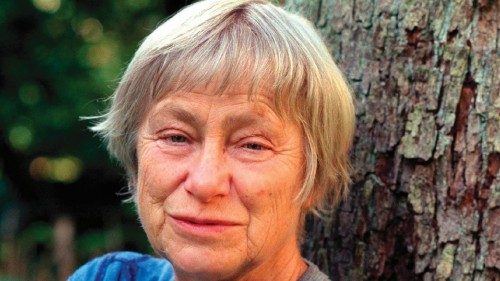

Portraits

Imagine a sentry on a tower, or a lookout at the top of a ship’s mast. She stands upright and fixes her gaze on the horizon, knows it so well that she remembers the line where sky and land meet, even in the darkness, ready to glimpse the lights and interpret the movements, whether that be animal, friend, danger, or dawn. This is what the prophets, both male and female of all times have done; alert as sentinels in history, and Dorothee Sölle too can be counted among those who have kept watch a lifetime for the city. A Protestant theologian, she was always concerned that “theology should not remain in the ivory tower of her repeating ‘Lord Lord’”. In addition, indeed, her thoughts ran alongside the political events of her day. Even her poems are steeped in history and geography, and each of her reflections are a praxis. This is why her theology did not die with her; on the contrary, it continues to urge forth the men and women of today.

Do not stay the same

Her surname of origin is Nipperdey (Sölle is that of her first husband), and her year of birth, in 1929, is the same as Anne Frank’s. Dorothee was born into a German family, but her childhood memories are as if divided in two. Her parents were opponents of the regime and at home, they did not restrain from talking about torture and deportations; at school, on the other hand, all speech was supervised. Splitting up must be a common experience for many children of her age, but as far as she is concerned, the feeling of living in a world told with double standards stuck with her forever, even after the war. Whatever the injustice, in fact, the world was divided between those who denounce and those who tell a mystified story, deluding themselves of their innocence. Sölle tried each time to be among the former, keeping a grip on reality even when it was frightening, but it is not easy. At times, it would be more natural for her to take refuge in the nihilism of certain philosophers she is studying at university, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre to name just a few. Putting the dark years of Nazism in parentheses and believing that everything is useless and senseless. Nevertheless, at some point she encountered a Christianity that is courageous and radical, not conniving, not reactionary, and convinced herself to study theology. She was inspired by disillusioned and acute theologians such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a leading figure in the resistance to Nazism, and Rudolf Bultmann, her professor and teacher, who linked his name to the theory of ‘dimitisation’; both German and Protestant, in different ways they exposed the hypocrisies of religion. When she concluded her studies, Dorothee Sölle had only one certainty: after Auschwitz, indeed after everything that had happened, theology could not remain the same.

Praying, that is, to change the world

In the early 1960s, in the midst of the Cold War, Sölle struggled with the separation from her husband. They had been married for ten years and have three children; meanwhile, she has never stopped taking an interest in what was happening around her and doing activism - against the rearmament of West Germany, for reunification with the East. During these politically and personally troubled years, she wrote Representation. A chapter of theology after the “death of God”. She writes it driven by a need, that of not lying to herself, and weighs every word with the seriousness of one who compromises herself personally. The text is published, but the subtitle is misunderstood and immediately earns her much criticism, as well as rejection by a publishing house. Sölle does not want to advocate the death of God, but the end of an image of God, that of “Mr. Fix It”, who intervenes to solve the unsolvable and relieves humanity of responsibility. The metaphor does not work because, quoting Teresa of Avila, “God has no hands but our own”: he does not intervene to replace us like clumsy children, but makes us capable and responsible for loving and practicing justice. Indeed, Sölle argues that prayer is not a way to look at God, but to learn to look at the world through God’s eyes and act to change it. In short, the only authentic way to pray is to actively participate in a reform of society and the church. Once again, do not ignore current events. The theory becomes concrete in 1967, the year of the Vietnam War. There were countless protests, and Dorothee Sölle and a group of friends also mobilized in their own way, inaugurating the Politische Nachtgebete, political prayer vigils, in Cologne. These are public moments, open to believers and non-believers alike, in the conviction that faith and politics are indivisible and that the Gospel acts by creating unhoped-for alliances. In effect, a kind of “ecumenism from below” is realised for the first time, where people of different Christian denominations, and even atheists, come together to dialogue on the pressing issues of life and public coexistence. The night meetings are true liturgical-political workshops, with public readings and discussion of topical issues. Data and skills are worked on, and concrete gestures are organized. After all, there is no prayer that does not bring with it the labors of the world.

Crossings and deliverances

In 1975, Sölle had not yet obtained a professorship as a theologian. She remarried, had another child, and when she received a proposal to teach systematic theology in New York she accepted and moved overseas with her family. Why could she not teach in her home country? It is a question her colleagues ask her many times. In the end, Sölle admits that her being a woman must have weighed heavily, both because it contributed to her attracting criticism - a woman taking the floor is detonating - and because the timing of an academic career is not designed for those who marry young, have children and deal with shattered relationships. For women too, therefore, Sölle begins to demand justice, and the freedom not to have to submit to a masculine way of working. In her American years, she prints Suffering. It is a text of mysticism but not mysticism: for Sölle, mysticism is also politics; waking is inseparably waking for the pòlis. Hers is therefore an “open-eyed mysticism”, which prevents Christianity from certain masochistic and self-centered drifts, and at the same time requires it not to be apathetic, but rather to take on social suffering, the cry of the poor. The theme of poverty and injustice, which has always been closest to Dorothee Sölle’s heart, led her to encounter liberation theology. In 1979, she lectured in Argentina against cynicism and consumerism, two sides of the same coin of capitalism. Figures such as the poet and Catholic priest Ernesto Cardenal, involved in the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, Oscar Romero, assassinated in El Salvador in 1980, or the Brazilian archbishop Hélder Camara fascinated her. In short, she lends herself to/she has been attracted by the call of Latin America and absorbs from here a new theological language, with the hope that the theology of liberation will make the crossing backwards with it and land on the shores of Europe.

Dorothee Sölle died on 27 April 2003 during a conference in Germany. Her life intertwines historical disenchantment and a commitment to disarmament, ecumenism and the fight against poverty, criticism of predatory capitalism and feminism (which becomes eco-feminism), through/until to mysticism “with open eyes”. Her theology is thought and practice at the same time, in it resonates from time to time, what is happening in the city, a pòlis without borders, the whole worldwide. Today we would say, “Everything is intimately connected”. However, such an integral and multidirectional vision of the justice of the Kingdom of God was then the lucid intuition of a female prophet. Of her voice the echo remains strong, the voice of a sentinel for the city, or of a lookout clinging to the mast. Animal, enemy, danger... Dawn, at last.

By Alice Bianchi

Doctoral candidate in Fundamental Theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University; Coordinamento Teologhe Italiane

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti