History

The Crimean War

The gruesome images of the war in Ukraine bring back memories of another terrible bloody Crimean war. Our Crimea. It was 1855 and the tiny Kingdom of Sardinia, defeated a few years earlier by Austria in the First War of Independence, decided to enter the geopolitical arena of significant foreign policy. On the advice of Count Cavour, his most trusted minister, King Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, sent an expeditionary force to the Black Sea alongside the British and French, to support a shaky Ottoman Empire against Russian expansionism.

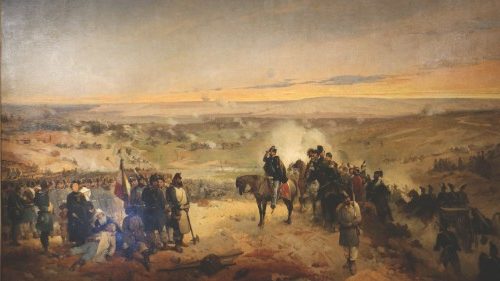

To glorify the enterprise, the king also wanted adequate propaganda. Therefore, the painter-soldier Gerolamo Induno was commissioned to paint a vast picture, The Battle of Cernaia, to glorify the battle that they had fought in the Crimea. Induno’s mighty canvas was exhibited in 1859, in a Milan that had just been conquered by the Austrians, and an immense crowd, inflamed by Risorgimento ideals, passed by to see it in deferential silence. Induno’s painting may have been art, but above all, it was a political proclamation. On closer inspection of the painting, among the soldiers, horses, cannons and gunpowder, the robes of two nuns tending a wounded soldier stand out. They are wearing grey robes and a large white cap, which was typical of the Daughters of Charity at the time. Moreover, it is clear that the two nuns are as much protagonists of the scene as the soldiers are. This was not a casual tribute, for they symbolized the collective effort of a Country that aspired to national unity and modernity, Catholics included.

The 1855 Crimean War represented a tough test for the Sardinian-Piedmontese army, which measured itself on an equal footing with the French and British armies, and against the Russian enemy. However, it was arduous for the Daughters of Charity too. On the instructions of their spiritual father, the Blessed Marco Antonio Durando, brother of General Giovanni Durando -who commanded one of the two Sardinian-Piedmontese divisions in the Crimea-, a group of courageous Vincentian sisters left the parish of San Salvario, in what was then the outskirts of Turin, the capital of the Kingdom, to take charge of military health.

“The government”, as can be read in the official history of the congregation, “asked the Daughters of Charity to follow the Expeditionary Corps of 15,000 soldiers sent to fight against Russia in the Crimea. Sister Cordero, the provincial bursar, offered herself for this dangerous mission and reached the shores of the Bosporus with 70 Sisters to care for the wounded soldiers and especially those struck down by cholera that was wreaking havoc among the troops. Several sisters left their lives there”.

It was not an easy decision. “At the meeting of the Provincial Council February 22, 1855”, we read in the book Florence Nightingale e l’Italia [Florence Nightingale and Italy], edited by the Order of Nursing Professions, “it was decided to send some sisters. The Superior General, Father Étienne, who was present at the meeting, emphasized the importance of the mission and the need for the choice of subjects to be judicious, because of the delicate task entrusted to them, which required reserve, prudence, discretion and the ability not to meddle in politics. All the sisters had to be up to the assigned task. Father Étienne emphasized the importance of the ambulances having a Sister Servant and of a member of the Provincial Council being part of the expedition; he asked for a small council to be formed, authorised to decide and to act according to the spirit of God in all unforeseen circumstances for which it was not possible to consult the superiors”.

It was a difficult mission in a foreign land and during a war. Nevertheless, caring for the poor and the sick was the vocation of these famous nuns, whose history goes back to 1600 in Paris. The Vincentians were the first to come out of the enclosure and launch themselves into the world. As the official history of the congregation recalls, “Luisa de Marillac and Vincent de Paul founded the innovative ‘non-religious’ community of the Daughters of Charity. St Vincent did not want enclosure for them; they did not want vows, habits, barred windows, or parlors. They had to live simply. They did not want a chapel. They demanded a house similar to one the poor had for themselves”.

From France, the Daughters of Charity had also arrived in Turin in 1837 and there they cared for the sick in their own homes; from 1839, they also had their own hospital. Those whom Induno immortalised on the canvas were two of the seventy-six Daughters of Charity who had arrived in the Crimea with the troops, in support of 400 nurses and 100 military doctors. They wore a long grey dress and white cloak, and mainly coordinated the work of the male nurses in the hospitals, acting as head nurses in a modern hospital. They supervised the distribution of food, laundry, kitchen duties, the cleaning and medicines.

However, the Piedmontese nuns were not alone. The French had also approached the Sisters of Charity to have them accompany the troops. The Russians tried to organise something similar for their troops too. “The departure of the Sisters of Charity for the camp”, we read in La Civiltà cattolica (1858), “produced an incredible effect on Russia. At first it aroused astonishment and even amazement; and as they did not want to fall short of the French in anything, so the Russians began to desire to know what they could do on their side too”. The British, then, not being able to count on Catholic nuns, asked the Ladies of Charity of London, the Care of Sick Gentlewomen, for help. So from England came a group of lay nurses led by Florence Nightingale, who would become famous in this war. The Times of London wrote a famous article about her, The Lady with the Lantern, because she went to the battlefields to recover the wounded. For her, too, there was the apotheosis of a magniloquent painting, The Mission of Charity, by Jerry Barrett.

Nightingale’s role in innovating the nursing profession was exceptional. Her figure as a professional and as a woman who would care for every wounded person, regardless of nationality, is considered to be an inspiration for the birth of the International Red Cross, shortly afterwards thanks to the Swiss Phillip Dunant. However, it would be ungenerous to erase the example that came first and foremost from the Catholic nuns. In her book Notes of nursing, which became a worldwide bestseller, Nightingale wrote of the Piedmontese sisters: “My opinion, formed on personal experience, is that the Italian woman is endowed with a special aptitude for caring for the sick. I derive this opinion from having seen the Italian sisters of St Vincent de Paul at work, attached to the Sardinian troops in the Crimea. The superior of the Italian sisters in the Crimea is one of the most distinguished women I have ever met in our vocation”.

This is perhaps the finest act of homage to Sister Cordero and her sisters. A dispatch dated December 17, 1855, signed by General Durando, has also been found, which states, “Miss Nightingale visited the Piedmontese hospitals on the Bosporus and greatly admired their layout. She was on the best terms with the nuns, of whom she held them in high regard”.

Finally, in the fortnightly magazine Le missioni cattoliche [Catholic Missions] (1880) about the French Vincentian nuns, an article reads, “In the hospices and pharmacies, after the French, the nuns accept the sick of whatever nation indiscriminately, and whatever religion they belong to. They are blessed by the Turks, who have the deepest respect for them and would not suffer others to do them the slightest injury. During the Crimean War, thirty nuns died in the hospices and ambulances where they cared for our wounded. They aroused such great admiration in the English that they allowed them to travel freely to their Countries from then on. The white cap of St Vincent de Paul is the only uniform that can circulate with impunity in England [Great Britain]”.

Once the war was over, the troops returned home. The enterprise had been bloody. Even more than the bullets, cholera had wreaked havoc among the soldiers. The Daughters of Charity returned to the convent-hospital in Turin, to care for the poor and the sick. Nevertheless, the memory of the Crimean enterprise was not lost. Count Cavour mentioned it in a parliamentary speech, stating, “The suppression of the Sisters of Charity would be the greatest of errors. I consider this institution as one of those that most honour religion, Catholicism, and civilization itself. I have lived many years in Protestant Countries, I have had relations with the most liberal men belonging to that religion, and I have often heard them extremely envious of the institution of the Sisters of Charity to Catholicism”.

Years later, in February 1868, when the Italian Parliament again debated the abolition of the Sisters of Charity from the hospitals, the former General La Marmora rose up, saying “Those who saw them in the Crimea performing their services on the battlefields and in the hospitals, cannot forget the courage and perseverance of these good women, who now laid down their lives to withdraw a wounded man from the lines, now sacrificed nights and nights of sleep to keep vigil at their bedside. After what they have done and are doing, it would be sheer ingratitude to expel the nuns”.

by Francesco Grignetti

A Journalist with the Italian national daily,“La Stampa”

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti