This low-rise block building of alternating earth tones called S-Dorm doesn’t mesh with the mammoth edifices jockeying for position inside the razor wire fences. The slanted shingle roof with minimal air-conditioning vents has no counterpart in the landscape of flat-topped “factory air” buildings filling the rest of this prison compound.

Clearly, this is no ordinary prison building. It’s even unlike any hospital I’ve seen, inside or outside of prison. This is psychiatric solitary confinement. It’s not easy for an inmate to get assigned to this place.

A major Florida newspaper reported that more than one out of every nine adult Florida inmates is severely mentally ill. That doesn’t mean sociopaths. That means people in need of medication and treatment. That number translates to about 7,000 inmates. It would take seven or eight air-conditioned prisons of 1,000 cells each to hold and treat that many severely mentally ill inmates. Those 7,000 prison cells don’t exist in Florida.

And it is not likely that those mental health cells will exist in Florida anytime soon. We Florida taxpayers want no part of that solution which we sneeringly call coddling criminals just because they are severely mentally ill. Our tax dollars are paying for punishment, not for treatment. Many of those severely mentally ill inmates will swelter in regular solitary confinement cells for years at a time. That’s standard drill for Florida’s mentally ill inmates.

Even worse is the fate of the mentally ill who are sentenced to death in Florida. Before coming to death row as a volunteer chaplain, I assumed that mentally ill people under a sentence of death in Florida had to be a rare anomaly. I was shocked to find out that the opposite is true. Mental illness is practically a subtext to the Florida death penalty. During one stretch of executions under a prior Governor, 7 out of 12 death warrants signed were for inmates with mental illness.

Many of the men who are placed in psychiatric solitary confinement need psychotropic medications that are strong enough to kill them in the ordinary heat of a Florida prison. So, they are sent here to psychiatric solitary confinement where the minimal air conditioning keeps the inside temperature just a shade cooler than the fatal level. No one wants to risk the wrath of Florida politicians and taxpayers if the inside temperature were to actually become comfortable.

Some of the inmates here are Catholic. Some receive Communion regularly. Today is the one day each month that I bring Jesus in my pocket to the Catholics in psychiatric solitary confinement.

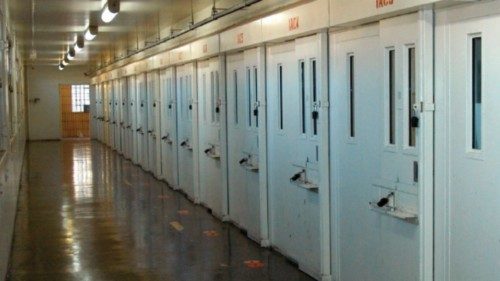

As I enter the wings, one at a time, the first thing that hits me is the silence. It is incredibly quiet. None of the shrieking, pounding, banging, kicking or pleading that is normal in regular solitary confinement in the summer heat. Here it is quiet in the extreme.

Otherwise, it seems just like regular confinement except the solitary cells in this unit all have steel and Plexiglas doors. There is still the feeding hole, called the food-flap, at waist level in each door. Each cell door is completely transparent. The man inside each cell is totally visible. To my surprise, this is almost harder for me to handle than the solid steel doors of regular solitary confinement.

One corridor called suicide watch houses those who have repeatedly attempted to take their own life in prison. Everything and anything in their hands could become a weapon of self-destruction. They wear only their skivvies and a tear away blanket. The corridor we are on today holds the men who are functioning at a level above that — some just barely. The ones who do well here will graduate back to T-Dorm where the restrictions are a bit milder and the supervision a bit less intense. But the psychotropic medications are still very heavy.

With an officer close at hand, I make the rounds cell to cell. In this special unit, reading material must not have staples. Rosaries must be “break away” string. Communion must be on the tongue — but I’ve been warned to watch for any sudden movement of the neck or face that would signal an attempt to bite my fingers. Thanks be to God, it has not happened.

As I close the sacrament of Eucharist with a middle-aged Catholic man, there is a scratching noise from a cell across the hall. Fingernails on Plexiglas and metal. It’s a young man. He motions me to his cell.

“What do you need?” I ask softly through the drilled holes in the Plexiglas.

“The voices,” he holds his hands to his head. “Please, make the voices go away.”

I turn to the officer who is escorting me. He nods and unlocks the food-flap in the young man’s door.

As I kneel on the concrete floor outside the cell, I motion to the youth inside, “Kneel down on the floor and lean toward the door, so I can place my hand on your shoulder in the food-hole.”

He falls to his knees. We pray. We pray renunciation of any involvement in the occult, in the Satanic or in the power of evil. We pray for protection by the Holy Angels, for the intercession of Our Lady and the Saints, and for his ultimate healing at the hands of Jesus Christ.

I give him a paper holy card picturing St. Michael the Archangel defeating Satan.

When we are done, the officer relocks the food-flap.

It is quiet again.

As I retrace my steps through S-Dorm and into the adjoining building, T-Dorm, memories from childhood intrude on the silence in my thoughts.

During my middle school years at St. Michael Catholic School in Livonia, Michigan, I frequently rose early while my parents and the rest of the family slept. My morning place is a basement corner near the laundry chute. There, in a knotty pine bookcase, my favorite books stand ready to yield their wisdom.

As morning noises of dad’s preparations for work and the drone of the radio news on WJR Detroit cascade down the laundry chute from the second-floor bathroom, I curl in the warm glow of a solitary bulb and consume my treasures. My favorite is a book by The Christophers, Three Minutes A Day.

Each morning’s offering is a brief account of real people facing real problems. In every case, their faith has shown the way, an answer, a power to overcome. It is a reality show in written form. The key to winning, the key to staying “on the island” of hope and perseverance, is faith. Again and again, in those inspiring tales, the phrase returns: Better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.

In a strange quirk of memory, that phrase and the glow of those mornings come flooding back on me as I step into a psychiatric solitary cell in T-Dorm. This dorm is not a pretty place. Here are housed the men whose life with mental illness, and possibly a host of other problems, has led them on a path to the most severe restrictions the law allows.

This place is too stark, too dangerous, and too real for any TV show. This is the reality of the plight of the mentally ill in an affluent society that refuses to pay for their care. This is the end of the road for many of those who are physically sick in mind and have fended for themselves on the streets without community services. This is the last stop on a train to hell in an affluent state that has closed thousands of civil mental hospital beds, leaving the care of the male mentally ill to the criminal justice system. If there is darkness, this is it.

And yet, the man I am here to see today is lighting a candle. For four years, despite the ravages of his illness, he has worked steadily to understand the Catholic faith. This morning, his efforts are to be rewarded.

The bishop will be joining us to baptize and confirm him and offer his First Holy Communion. Six officers accompany us to his cell. They open the cell door slowly. We enter.

He is in shackles and waist cuffs, wearing a helmet and spit shield. The officers remove the helmet and shield and fall back, flanking us with a semi-circle of observant protection. The bishop dons his stole and begins the rite of Baptism. As the words of exorcism fall from the bishop’s lips, the man begins to tremble. By the time the blessed water is poured upon his head, he is flowing with tears, whispering over and over, “Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Jesus.”

Finally, I break the quiet pause after his First Communion.

“You have become a part of our family of faith. A cloud of witnesses surrounds you. You are not alone anymore.”

To myself I think, Thank God, you have chosen to light a candle.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti