“On June 1,1310, a young philosopher, the Valenciennes beguine Marguerite Porete, was burnt at the stake; in 1524, the mystic Isabel de la Cruz was tried and later sentenced to life imprisonment by the Inquisition of Toledo; in the middle of the 17th century, the educated Jansenist nuns of Port Royal were deported by the Archbishop of Paris; in 1912, the work of the restless theologian Antonietta Giacomelli (Adveniat Regnum Tuum), who wanted to call for a liturgical reform in the Church, was considered dangerous and placed on the Index of Forbidden Books. These are some of the protagonists of Adriana Valerio’s book, the daring women who dared to stand up to the ecclesiastical courts, who were judged not to be in line with the directives of Catholic orthodoxy and therefore considered ‘heretical’”.

Thus begins the book Eretiche. Donne che riflettono, osano, resistono [Heretics.Women Who Reflect, Dare, Resist] (ed. Mulino) by the theologian and historian, Adriana Valerio. The author commences by stating that “women and heresies is a complex issue. […] It cannot be considered a defined category - because the demarcation with orthodoxy is not always precise and depends on the point of observation of those who believe they possess the truth. Moreover, it is a relative concept, in that it is bound to the dynamism of history, to the subjects who interpret it, to the theological and political contexts and to the cultural and religious changes that pass through it”.

Prophets, mystics, false saints, witches, reformers and freethinkers animate the vast population of heretics, but the book focuses on a few cases “readable within a proposal for change and reform in the Church”. Here are some of them, in brief, as Valerio recounts them.

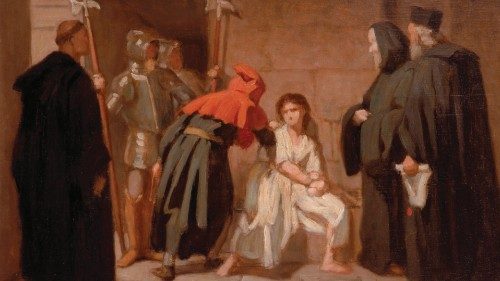

Marguerite Porete

In Paris, June 1, 1310, Marguerite Porete a young woman, the Beguine of Valenciennes, was burned along with her book The Mirror of Simple Souls, which had been judged heretical in some of its parts. It was the French inquisitor, the Dominican Guillaume Humbert, who put her on trial. To escape death, she was given the chance to repent, but refused to recant and, adamant in her silence, was handed over to the authority of the magistrate. The stake was supposed to erase the memory of the woman and her writing, but, fortunately, a few copies circulated anonymously in Europe until the discovery of a codex by the scholar Romana Guarnieri, who was able to identify it in 1946 and reconstruct its history. Marguerite did not demand the elimination of the institution but, rather, proposed a coexistence of two levels of belonging to the Church. The first of these two levels was marked by the need for a life marked by rules, devotions and virtuous deeds; the other, characterised by the freedom of those who, by uniting themselves to God in the love that envelops everything, would manage to acquire freedom.

Guglielma of Milan

We have little information about Guglielma since her story can only be reconstructed through the inquisitorial trials held in 1300, a full twenty years after her death. We do know that in Milan this woman of high social standing had forged ties with the Cistercian abbey of St. Mary of Clairvaux, which had allowed her to live in a house near the parish of San Pietro all'Orto. Here she soon gathered around her a community of believers who venerated her as a teacher and saint. Guglielma’s death on August 24, between 1281 and 1282 marked the beginning of a process of sanctification. When the tomb moved to the abbey and became a place for prayers and meetings, the monks welcomed the pilgrims, who arrived in large numbers, with sermons and celebratory feasts, thus promoting her cult. The worshippers, therefore, were not considered heretics, but faithful children of the Spirit. Guglielma, however, went from being a saint to a heretic within a few years and a trial was opened against her and her disciples in 1300. A saint in life and a heretic post-mortem, first venerated and then persecuted. Guglielma’s human journey led to an alternative theology. The incarnation of the Holy Spirit, which her woman’s body made visible, connected not only to the mystical-contemplative strand that refers to the feminine expressibility of God, but also opened up to the utopian image of a Church institution that places women at its summit.

Joan of Arc

An inverse path to that of Joan of Arc, who died at the stake in 1431, at the age of 19. First considered a heretic and then taken to the altars, not because she deified femininity, but because, on the contrary, she wore men's clothes.

Clothes, in fact, indicated a social and substantial condition and for a woman to wear men's clothes meant that the Church was opposing the natural order, wanting to take on tasks that were prohibited. Joan did not renounce it because for her, clothing was closely linked to the mission she wanted to fulfil beyond its gendered connotation.

The alumbradas

The Spanish Inquisition paid particular attention to the “illuminated” (alumbrados) movement, especially the alumbradas, those visionaries who, immersed in the love of God, relived and preached passages from the sacred text, reworking them in the light of their own spiritual experience, appealing to the words of Paul, “The letter kills, the spirit gives life”. Leading a group of alumbradas at the beginning of the 16th century were two charismatic figures, linked by friendship and both of conversa origin, i.e., belonging to a converted Jewish family. Their names were Isabel de la Cruz, a Franciscan tertiary and preacher, and María de Cazalla, a laywoman, mother of six children and wife of a wealthy bourgeois. Isabel was arrested by the Toledo Inquisition in 1524 and María de Cazalla in 1532, after she had replaced her friend as leader of the group. The alumbrados included the humanist Juan de Valdés, who landed in exile in Italy from Spain following the condemnation of his work Dialogue of Christian Doctrine (1529).

In Naples, from 1534 until her death, she led a cenacle of women and men in search of an inner dimension of faith at the expense of the external forms of rituals. The participation of aristocratic women in Waldesianism, Costanza d'Avalos, Maria of Aragon, Isabella Bresegna and above all Giulia Gonzaga, who considered her spiritual heir, can be described as intense.

Giulia Gonzaga

The spiritual relationship between Valdés and Countess Gonzaga gave rise to the Christian Alphabet (1545). After Valdés’s death in 1541, the countess undertook to disseminate his manuscripts and, despite her aristocratic affiliation, she was not spared an investigation by the Inquisition for her relations with another exponent of Italian evangelism, the humanist Pietro Carnesecchi. She died, however, only “smelling of heresy” in 1566, before the trial could take place. Her home was searched, her correspondence seized and Carnesecchi was imprisoned, tortured and put to death the following year.

Vittoria Colonna

The marquise of Pescara, the poet Vittoria Colonna, was also under observation because she was part of a dense network of relations with reformers engaged in reflecting on delicate questions of faith. In addition to her presence in the circle of Giulia Gonzaga, she was a guest at the lively pro-Protestant court of Renata of France in Ferrara and had extremely close contacts with the Viterbo community, which met around the English cardinal Reginald Pole to discuss the Bible and the theological issues raised by Lutheran demands. She was in correspondence with the writer Margaret of Angoulême, Queen of Navarre, a central figure of the French religious reform in contact with Calvin and Melanchthon, and knew well the cultured duchess Catherine Cibo, a privileged interlocutor, on issues of justification, of the Capuchin preacher Bernardino Ochino, who later went on to the Protestant Reformation. She was, finally, the inspirational muse of Michelangelo, who was also part of the group of these spiritualists, who designed a Pietà, a Christ on the Cross and a Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well for her, in line with the experience of an intimate and intense religiosity, marked more by doubts than certainties.

Juana Inés de la Cruz

The Mexican nun, Juana Inés de la Cruz, was also accused of pride. Besides poetry, she was interested in mathematics, astronomy, music, Holy Scripture and theology. Unfortunately, she got into a dispute over the interpretation of a biblical passage with a respected Portuguese preacher, the Jesuit António Vieira. In defending herself against the accusation of devoting herself to the study of sacred texts, an activity forbidden to a nun, she developed her own reflection. This personal approach involved interweaving autobiographical memories (her passion for studies) with biblical and profane references (the female models who distinguished themselves for wisdom and science) and historical-doctrinal reflections (the role played by women in the history of the Church and the necessity of study for women as useful and beneficial).

Through historical testimonies drawn from the lives of learned women, Juana defended their right to study the Bible, which was to be authorised and granted to all those with talent and virtue, women and men alike. For the Mexican nun, biblical interpretation was based on a precise contextualization of the text examined. Hence, according to her, Paul’s verse “Let the women keep silence in the assembly” was directed against the custom, practiced in the early Church and reported by Eusebius, according to which women taught doctrine to each other in the churches. However, since their chatter disturbed the apostles while they preached, they were ordered to be silent. In 1692, Sister Juana was forced to abjure before the Inquisition tribunal. Pressure from her confessor and the local church drove her to give her copious library (more than four thousand volumes), her musical and mathematical instruments to Archbishop Aguiar y Seijas to sell, and to devote herself to a rigorous ascetic life that would soon lead to her death.

Jeanne Guyon

Included in the restless Quietism current was the bold journey of faith of the French mystic Madame Jeanne Guyon (1648-1717) who, through her fragile speaking body, embarked on a “path of the intellect and heart” as a theological alternative to rationalism. She felt she had an apostolic role to play, and mystical experience persuaded her that women, because of their humility and availability, were better suited to narrate divine truths. The concrete experiences of women's lives made it possible to approach truth not through conceptual systems, but through an itinerary of sapiential faith, what Guyon called “savoury faith”. In her, the spiritual mother of Abbot François Fénelon, emerges the exaltation of feeling against Cartesian rationalism, the passive abandonment to the love of God that makes one impeccable and indifferent to external works and devotional practices, stating “God wants to be loved, not known”(Les Torrents Spirituels, 1682). In 1695, Madame Guyon was arrested, tried and exiled; while in 1699, Fénelon was condemned.

The Witches of Salem

Adriana Valerio emphasizes that witch hunts cannot be generalized by attributing the blame predominantly to a geographical region or a religious confession, since it was not only the Catholic, but also the Protestant Churches that participated “in this collective delirium”. Local causes accentuated the phenomenon by mixing political and religious motivations. For example, Waldensians and Cathars, who had taken refuge in the Western Alps, became synonymous with people dedicated to witchcraft and, consequently, trials and persecutions intensified in the Dauphiné. At the end of the 17th century from Europe, the phenomenon landed in the colonies of New England where 144 people were tried and tortured in Salem, Massachusetts. Later, it was believed it had been a case of collective hysteria.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti