Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him, and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was; and when he saw him, he had compassion, and went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; then he set him on his own beast and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And the next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, ‘Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, I will repay you when I come back.’ Which of these three, do you think, proved neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” He said, “The one who showed mercy on him.” And Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.”

Luke 10, 30-37

Why has the Good Samaritan parable directed my existence in such a decisive way? I can trace it as occurring in Heidelberg many years ago. I was about to graduate with a law degree and happened to attend a lecture on Nietzsche and Expressionism. While listening to the lecture, I realised for the first time what it meant to talk about a work of art as an act of love towards others. That was how I decided to pursue a second degree in Philosophy and History of Art.

Later on, I was so struck by Didi-Huberman’s expression “what we see looks back at us”, which I felt called upon me to investigate the phenomenology of the gaze and in particular the Christ’s gaze in Romano Guardini’s Katholische Weltanschauung. I realised then that the work of art and love have one thing in common, which is they both originate from a creative act. The one and the other configure a space of knowledge in which things and people reveal themselves in their deepest being. In one of his Homilies for the liturgical year, Guardini approached the mystery of proximity, reflecting on the space to which the parable of the Good Samaritan also alludes. We usually believe that Luke's purpose is to remind us that it is our duty to love “everyone”. However, this would only be true if, as Guardini observes, the love of one’s neighbour was, or was understood to be, solely a series, albeit dutiful, of acts of goodwill. Instead, loving means much more. In order to be able to love the other, it is first of all necessary to “see” him for what he is, in his being-ness (Da-Sein). My gaze has to be directed at the other without reserve or prejudice so that, in a creative act, I reserve for the other a space in which he can present himself before me with all that he feels, suffers and desires. Moreover, only love can “see”, because it is able to open itself to all that is already there and in the process of becoming. In the loving gaze, in fact, I allow the other to take form and manifest himself before me.

In the parable, is this not what differentiates the Samaritan's gaze from the Levite's and the Priest’s way of “seeing”? There must, therefore, be an initial openness, even before the one before me manifests themselves to me as my neighbour. Such love - Guardini continues - looks with a gaze similar to that of the artist in the creative act and is a reflection of the love of God who, in his creation, sets us free to move lovingly towards Him. Through this openness, people come into my life who, destined to come to me, are entrusted to me as a neighbour. As Guardini observes, “Knowledge is a creative act, in love”.

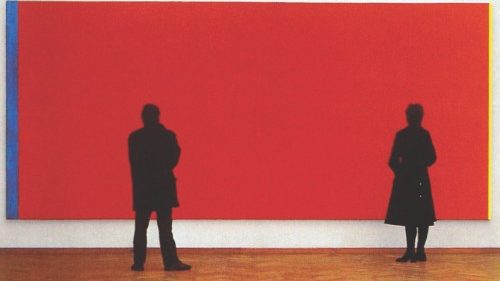

In the Last Judgement, Michelangelo highlights this “space” of knowledge. He shows the depicted figures looking at Christ with a terrified gaze and in the act of covering their gaze with their hands or, like Saint Peter, approaching him angrily, showing Christ the keys to this “opening”. The plethos (the crowd) is only able to see with their gazes’ one of the two arms of Christ, which is the one that is condemning. Truth lies “between” opposites. Thus, Michelangelo in the Last Judgement configures in his work of art a space in which humanity can enter, in which it is able to give Christ the space in which He can manifest Himself for what He is. Similarly, Barnett Newman in his painting Who is Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue forces the viewer to place himself in front of the canvas so that they can experience a red space of infinite dots and feel the pigments physically. This creates a sublime and intimate space for the viewers to return to themselves, and where God can dwell.

Guardini describes love of one’s neighbour as a valid criterion not only for human love encounters, but also for love encounters with other “beings”, with things and with works of art. On closer inspection, art itself becomes the “neighbour” in the act of love of artistic creation and even in the gaze of the observer when he or she encounters the work of art. In Guardini’s Homily on Luke’s parable, all of Guardini’s key terms appear as “looking”; “configuring”; “creative act”; “space”; and, “encounter”. In one of his most important insights, Guardini argues that love looks creatively because in it, selfish self-assertion withdraws and gives space to the human being who is there before me, so that they can become clear to my world. All this for me also transpires from the words of Jesus and the testimony of the Samaritan, which continue to touch me deeply as a woman, mother, wife, believer, teacher and art lover.

by Yvonne Dohna Schlobitten

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti