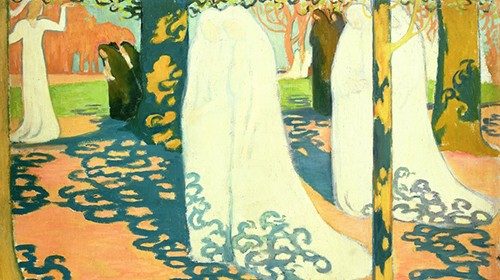

“Then the kingdom of heaven shall be compared to ten maidens who took their lamps and went to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish, and five were wise. For when the foolish took their lamps, they took no oil with them; but the wise took flasks of oil with their lamps. As the bridegroom was delayed, they all slumbered and slept. But at midnight there was a cry, ‘Behold, the bridegroom! Come out to meet him.’ Then all those maidens rose and trimmed their lamps. And the foolish said to the wise, ‘Give us some of your oil, for our lamps are going out.’ But the wise replied, ‘Perhaps there will not be enough for us and for you; go rather to the dealers and buy for yourselves.’ And while they went to buy, the bridegroom came, and those who were ready went in with him to the marriage feast; and the door was shut. Afterward the other maidens came also, saying, ‘Lord, lord, open to us.’ But he replied, ‘Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.’ Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour.

Mathew 25, 1-13

I confess that as a young girl, when I heard this parable I was puzzled, a bit like the fable of the grasshopper and the ant. Then, as time passed, I realised that it is those who dance in life who will enter the banquet, and that no one can dance it in place of another. For prudence sake, this does not mean to place oneself in safe position, but to look far ahead, beyond the petty urgency or fatigue of the moment, and to extend one’s life always further. To follow a dream, a vision, an invitation that comes from outside of us and that we welcome with enthusiasm. As Emily Dickinson wrote in poem 1619, “Not knowing when the dawn will come, I leave every door open”.

The word “Saggio” [Wise] has two Latin roots; the first is the same as “sapidus” (that which has flavour, what is not insipid) from which we also derive “sapienza” [wisdom]. The second, is “exagium”, which refers to tasting, evaluating, and discerning. A person is wise who does not let life slip by, but savors it, takes initiatives, and risks.

The word “Stolto” [Foolish], on the other hand, comes from the root “stal”, which indicates fixity. The fool stands still, does not act, does not set out. He may secure himself, but in the end he realises that he has not really lived.

This is because life is built day by day, and is a response to its provocations, its urges to the unpredictable that always disorientate us and set us in motion. The way we respond helps us to take shape, to become who we are, and this is why we cannot live the life of others, or respond in their place. Moreover, there is no turning back, when we realise that perhaps we should have lived differently. The wedding feast is made for us, it is the celebration of the beauty of fraternity and filiality, of abundance and fullness, where each person will be recognised for who he or she is, because he or she will be wearing the garment woven with life, which is the form he or she has taken over time.

To walk in the light even in the midst of darkness is possible, because the oil that lights our lives is always available to us, and all we need do is desire it and seek it. The quantity that the small vessel of our ego can hold is sufficient. We are small, we have limited capacity, yet what little we have, if we are able to put it all in, can be enough.

And, then the art of waiting must be learned.

For we know neither the day nor the hour. There is no algorithm that can anticipate it for us with sufficient approximation. When we admit that we do not know it is almost mortifying in the age of hyper-control, but seen from a different perspective it is liberating.

It is precisely because we do not know that it is up to us to make sense of the wait, and to prepare ourselves to enjoy the beauty of the encounter and celebration to the fullest.

Sleep and death, wakefulness and life: the equation is not so clear-cut. We think we are awake but in reality we are all too often switched off; sometimes as if we were walking dead. We are unable to yearn for life, to allow ourselves to be carried by its force, to put our own spin on it. We are already dead before we die, and when our time comes, we cannot turn back. As Victor Hugo wrote, “waiting is life”.

To “remain awake” is therefore more than a recommendation to not fall asleep; instead, it is an invitation to live, to keep our eyes and hearts open, to allow ourselves to be amazed, to know how to read the signs that present themselves. Wakefulness is a condition of attention and also of care, with which we devote ourselves because we are convinced that it is worth it.

It is not out of fear that we must wait for the bridegroom, but in order not to miss the wedding feast. To savor the surplus of water that becomes exquisite wine, as in the wedding of Cana. The wedding feast is the symbol of a tasty, joyful conviviality; of a fullness that is fulfilled and in which one can only participate if one truly desires it. We are all invited. It is up to us to accept the invitation and prepare ourselves, to live in large measures. Only those who have truly lived, even with their limitations and shortcomings, can be part of the feast. Which is not a prize in the afterlife, but the fulfilment of what we have already learned to enjoy. As Emily Dickinson writes, “Those who have not found paradise down here - will miss it up there”.

“Wakefulness” after all, is an appeal to our freedom. If the invitation interests us, we will stay awake and make a kairos of the night towards the encounter that gives meaning and beauty to our lives - a beauty we could never make with our own hands. If we fall asleep, if we allow ourselves to be stunned or seduced by other calls, we will only be able to blame ourselves for not participating in the feast of life, which has been prepared specifically for each one of us.

by Chiara Giaccardi

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti