Frequently, in death penalty talks around Florida and around the country, I confess to the audience that thirty years ago I was totally ignorant about the realities of Florida’s death row. How else could I have started as a volunteer chaplain on death row on August 9, 1998. August is the height of the summer heat.

Anyone who really understands how death row works and the realities of its conditions of confinement, would have begged to start in the winter. I did not know enough to ask for that.

My mentor, Fr. Joe, is leading me cell-to-cell, introducing me one-by-one, to the men Florida is holding in these 2 meter by 3 meter cages until we kill them. The heat is off the chain. The humidity is at least 99%. All resulting in a thermal index in the hundred-plus degrees Fahrenheit range.

This prison heat is not unique to Florida. One of the extreme stresses on both inmates and corrections officers in the U.S. Deep South is the intense summer heat and humidity inside prisons without any climate control.

The ribbon of concrete I’m walking traverses the barred front doors of fifteen cells. In prison, those front doors are called “gates”. And this walkway, which is sandwiched between the cell-gates to my right and the steel-barred wall to my left, is called the “gatewalk”. It stretches from one end of the wing to the other and stays damp and slick all day.

In no time at all, both Fr. Joe and I are soaked to the skin in our own sweat and the condensation from the air. My thigh and back muscles are screaming for relief from the physical stress of trying to avoid slipping and falling on the damp concrete.

Decades ago, when I was working factory jobs to put myself through college, one job that lasted 9 months involved handling hot and cold steel stampings. The temperature and heat on Florida’s death row brings that experience to mind. But the summer humidity here in Florida drastically magnifies the impact of the heat on the human body.

I’m thinking to myself, I don’t know if this is hell, but it sure feels like it, as Fr. Joe stops and turns to me saying, “These men are God’s children. How can we keep them in these conditions?”

In raising my five children, I learned that when the burden of a task feels overwhelming, we must cut it down to size. Identify smaller pieces and rewards that we can achieve en route to the ultimate goal.

That learning kicks in as I contemplate each corridor of 15 or 16 death row cells. Inevitably there will be one or two cells in each corridor that hold an inmate who will recharge my draining energy with his warmth and his enthusiasm for our brief cell-front visit. Fr. Joe introduces me to just such a man on this first visit to this place.

“This is Juan,” my drenched mentor smiles at us both. “Juan is a very good man and a strong Catholic. He is a regular Communicant.”

I jump into the conversation stream to introduce myself. “I am a new volunteer to help Father Joe here. My name is Dale but everyone has already started calling me Brother Dale.”

Juan reaches through the bars to wrap his hands around mine. “So glad you are here. Fr. Joe needs all the help you can give him, especially in this building.”

As the weeks pass, my new friend is consistently welcoming and sincere. He also shares with me much of his journey on Florida’s death row.

“When I came here, I couldn’t read or write a word of English.”

“You’re kidding,” I am truly amazed. “How have you learned the language?”

“Right here!”, he smiles and motions to our surroundings. “My brothers here on death row have taught me how to read and write.”

My surprise cannot be hidden. Juan responds to it.

“Out there,” he motions broadly toward the windows in a gesture that takes in the world outside the fences, “They call us all monsters. But some of us are innocent, and most of us have a very complicated story.”

I have no clue how to respond. In the Fall of 1984, when Juan came to death row, I was still a high finance lawyer in Miami. I was still supporting the Florida death penalty which I knew nothing about.

I vaguely remember hearing about Juan’s conviction and death sentence in 1984 in the local news reports that touted life for life. It never occurred to me that we could easily sentence an illiterate, itinerant fruit picker to death even though there was no physical evidence connecting him to the crime.

Well, that is exactly what Florida did to Juan! And now, fourteen years later, I’m standing at his cell on death row.

“Juan,” I start cautiously, “I sense no bitterness or anger in you. How is that possible if you are innocent?”

“Just because they did this to me, doesn’t mean I’m going to beat-up myself or them. God will deal with them.”

After studying Juan’s case and making many more Communion visits at his cell, I get up the nerve to ask, “Juan, assuming the courts let you go, what will you do then?”

“That’s a no-brainer,” he smiles. “I will spend every ounce of my energy working to end this horrible death penalty, so that others won’t have to go through this even if they are innocent, too.”

By the end of 2001, Juan has become much more than a friend to me. He is truly a brother. I always look forward to our catching up at cell-front on my Communion rounds, hearing about his mom and how things are going in his case.

Then, in January of 2002, I come to his cell and find it empty.

“Where’s Juan?” I ask inmates and officers. No one knows.

They came and told him to pack his stuff, is the stock reply. Good intel can be very hard to come by on Florida’s death row. Nobody on staff wants to be caught on camera confirming the rumor that a death row inmate has been released for innocence.

Conventional wisdom in Florida is that everybody on death row is guilty of something. Even though since 1976, Florida has had 30 men released from death row with evidence of innocence.

All I can do is hope that Juan is in fact back with his family in the Caribbean. It is likely I will never see him again.

Then in the Fall of 2004, my wife Susan and I are in Montreal for an international conference on ending the death penalty. It is a large multiday gathering, and the emcee is Ms. Bianca Jagger. As I finish my late afternoon presentation, Ms. Jagger returns to the podium to introduce the next speaker. That’s when it happens.

I am walking across the stage from the podium toward the stage-exit on the opposite side. Coming toward me from that very same exit is a man about my height. His silhouette looks vaguely familiar in the stage lights. As we draw closer to each other it suddenly becomes clear that he is my brother Juan. I have not seen Juan since he was released from death row almost two years earlier.

The recognition hits each of us at the same time. We spontaneously react by breaking into a run toward each other. And there on the stage in Montreal in front of over 2,000 people, I hug my brother Juan with tears streaming down my cheeks. We have been circling around each other ever since.

Juan and I have shared a dozen talks presented to students in high schools and colleges on the Journey of Hope in Texas with our dear friend Bill Pelke. We have shared the stage at Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida and in numerous forums in Orlando, Tampa and Miami.

And most recently, just last month, Juan and I shared the audience at a major Catholic Conference at Georgetown Law School in Washington, D.C. Bishop Felipe Estévez, the Florida Bishop from St. Augustine who issued the profound pastoral letter on ending Florida’s death penalty, had invited me to be a co-presenter with him. What a double treat to find my brother Juan also there speaking.

The April conference was much broader than just the death penalty. It delved deeply into how our Catholic teaching and traditions equip us to reform our criminal justice system. Juan — a migrant Catholic who had spent more than 17 years innocent on Florida’s death row — had the ears and hearts of every participant in that conference.

For this writer, that conference was especially poignant. This was my first ministry trip since January 2022, when I was struck down by COVID in the midst of a weekly ministry trip to Florida’s death row and solitary confinement prisons. My dear wife drove over 400 miles to fetch me and carry me back to Tallahassee where I was admitted to the COVID ward of the regional hospital.

I have recently started driving again for short distances. And I hope that by this summer, the doctors will allow me to return to active involvement in Florida’s prisons. But in the meantime, I thank God that I was able to share another great faith experience with my Brother Juan.

NB: The Florida death penalty case of Juan Roberto Melendez is presented in The National Registry of Exonerations and is attributed to perjury, false accusations and official misconduct.

©2022 Dale S. Recinella, Tallahassee, Fla. USA

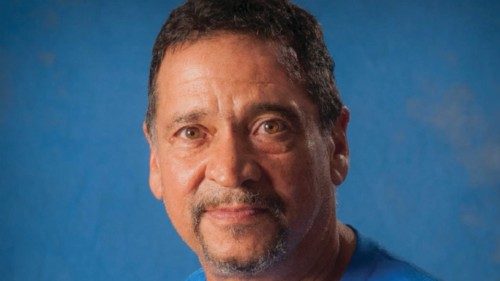

Dale S. Recinella *

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti