It inaugurates a family that extends the bonds created by marriage and childbirth

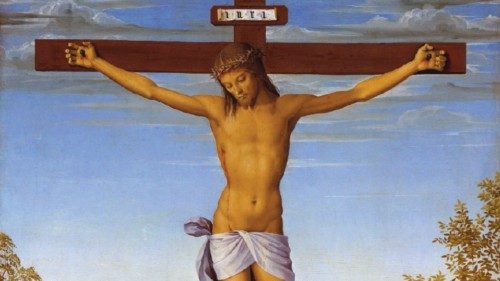

“When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home” (John 19:26–27). Jesus inaugurates a family that extends the bonds created by marriage and childbirth. For Jesus, “Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother” (Mark 3:33–35). John 19:26-27 opens the conversation of women and families to multiple observations. Here are four.

First, Jesus establishes what anthropologists call “fictive kinship units”: families not defined by marriage or biology. Women religious, called “sisters,” exemplify such units. For women who resisted marriage, for widows or divorcees, for women who were infertile or whose children had died, Jesus’s invitation to this new family would have been especially welcome.

Second, most women Jesus encounters have no husband present: Mary and Martha, Mary Magdalene, Joanna and Susanna, Simon’s mother-in-law, etc. With the exception of Mary and Joseph, only once, or perhaps twice, does Jesus speak to a married couple (you can guess who they are). For Jesus, marriage and childbirth do not exclusively or even primarily determine identity.

Third, tradition holds that this Beloved Disciple at the Cross is John the Apostle, whose mother appears in Matthew 20:21-22. The “wife of Zebedee” asks Jesus, “Declare that these two sons of mine will sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your kingdom.” She deos not realize the implications of her question. The two who will be on Jesus’s right and left are the two men crucified with him (Matthew 27:38). At the cross, where only Matthew locates the wife of Zebedee, she realized the import of her question as well as the sacrifices Jesus asks his new family to make.

In Matthew’s Gospel, the wife of Zebedee is at the cross, but she does not accompany the other women to the tomb. Nor, according Matthew 26:56, are the disciples at the cross, for they have forsaken Jesus. I imagine that after the Crucifixion, this dedicated mother returned to Galilee to encourage her sons. And by seeing the Beloved Disciple as John the son of Zebedee, we also learn that Jesus’s mother will find companionship with another mother whose son was killed by the local political authority, for Herod Agrippa has James killed in Jerusalem (Acts 12:2).

Fourth, in John 19:26, Jesus calls his mother “woman,” the same address he uses for several other women, with each reference related to a family. At a wedding, the beginning of a new family, Jesus’s mother, never named Mary in the Fourth Gospel, tells her son that the hosts have run out of wine. Jesus responds, literally, “what to me and to you, woman? My hour has not yet come” (2:4). The mother, unperturbed, tells the steward to obey Jesus’s instructions. She is a mother who understands her son, and he is a son who listens to his mother.

To the Samaritan at the well, Jesus says, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem” (4:21). Repetitions of “woman” and “hour” connect Cana’s wine to Samaria’s living water. Jesus then tells her, “You have had five husbands, and the one you have now is not your husband” (4:18). Those who see the woman as sexually suspect, as divorced by heartless men, or as otherwise dishonorable impose incorrect views on the text. Had the woman been dishonorable, the Samaritans would not have believed her announcement that she has met the Messiah (4:29). This first successful evangelist then facilitates a symbolic wedding between Jesus and her people.

John’s third use of “woman” is from a passage missing in earlier manuscripts of John’s Gospel, that of the “woman taken in adultery” (8:1–10). Jesus’s questioners, testing him, ask, “Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” (8:5). They are seeking not to kill her, but to trap Jesus. If Jesus says, “Stone her,” they will condemn him as barbaric, for Jewish tradition seeks to avoid capital punishment. If he says, “Don’t stone her,” they can question his authority. Jesus escapes the trap by famously telling the one without sin to cast the first stone.

When the questioners leave, Jesus asks, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” (8:10). She replies, “No one, Lord.” He responds, “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and do not sin again” (8:11). Jesus does not forgive her—that would be a matter for her husband. But he does grant her, and her marriage, a second chance.

Finally, the angels at the tomb ask Mary Magdalene, “Woman, why are you weeping?” (20:13a). Jesus repeats, “Woman, why are you weeping? (20:15). Mary thinks Jesus is the gardener; only when he calls her by her name does she recognize him. Mary’s reunion with Jesus—in a garden, mistaken identity, a recognition—suggests the Hellenistic romance, popular novels of separated lovers. But just as Jesus does not marry the woman at the well (contrast Rebecca and Isaac, Rachel and Jacob, Zipporah and Moses), again he breaks convention by telling Mary to stop clinging to him and to proclaim his resurrection. The goal here is not marriage but being the apostle to the apostles.

Each “woman” so-called displays distinct gifts, needs, and family situations. All are welcome in his Jesus’s where mothers and sisters are defined by what they do, not by marital status or childbirth.

by Amy-Jill Levine

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti