Theological zoology being studied at Münster

Lambs that wag their tails. Pigs that live in the garden of their homes. Hens that seek the caress of children. Even octopuses that affectionately stretch out their tentacles towards us, like the one that reached out to the hand of South African diver Craig Foster who, thanks to his extraordinary images, won an Oscar in 2021 with the documentary Octopus teacher. This profound article title, refers to how animals, even the most unlikely ones like a cephalopod, are teaching humans that there is an emotional and participatory commonality that is prompting not only philosophical and juridical reflection but has also laid the foundations for the creation of the Institut für Theologische Zoologie, in Münster, Germany in 2009.

In the institute, Christian theologians and those belonging to Eastern religions, Hindus and Buddhists, the latter children of a religious culture where the boundary between human and animal is less clear and less utilitarian. At the Institut für Theologische Zoologie theological thinking is dynamic and at the same time seminars on encounters between humans and animals are organized, and pet therapy and workshops of direct experience to find a ground of mutual recognition are available.

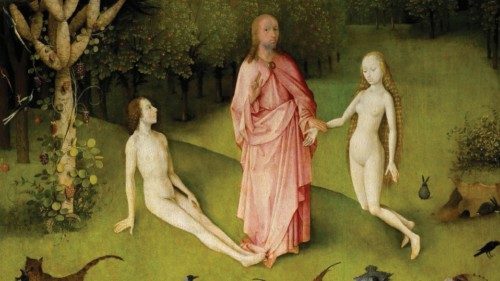

As the founders indicate, the main purpose is to “change the theological paradigm” and correct “an error” of modern theology on the fate of animals. For centuries they have been considered instruments without a soul and therefore inferior, undeserving of being thought of in any other light, or consideration. The error, write the Münster scholars, is not only harmful to animals but leads to a false conception of Creation and of God and this, as Thomas Aquinas warned, “distances men from the Creator”.

For the theology of animals, therefore, these non-human creatures possess a divine breath that makes them worthy of being part of the history of salvation, and this is not an absolute innovation of Christian thought, but sinks its vision in a reading of the Bible. The verses of Ecclesiastes, among many others, are very clear: “Surely the fate of human beings is like that of the animals; the same fate awaits them both: As one dies, so dies the other. All have the same breath; humans have no advantage over animals. Everything is meaningless”.

This is Pope Francis’ vision, as expressed in his encyclical Laudato sì, “other living beings have a value of their own in God’s eyes” because “Each of the various creatures, willed in its own being, reflects in its own way a ray of God’s infinite wisdom and goodness. Man must therefore respect the particular goodness of every creature”.

It is easy to imagine that this moral vision is also the fruit of the times we live in and of the environmental catastrophe we hope to avert, but what is really new, even in the eyes of ordinary people, are the scientific discoveries about the extraordinary emotional and cognitive capacities of animals. For example, in 2012, a document signed in Cambridge by the greatest neuroscientists on the planet established that all vertebrate animals and cephalopods have self-awareness. Again, in 2013, research confirmed what dog owners have always known, namely that they feel emotions similar to human emotions, a consideration also extended to animals that we normally destine to the cruelty of intensive farming. “This forces us to a new sensitivity and therefore to a new relationship with them”, states the WCW Father Martin M. Lintner, Servite, professor of theological ethics in Bressanone, and former president of the International Association of Moral Theology and Social Ethics. “A relationship that must take into account not only respect for the species but precisely for each individual animal”. Therefore, animal theologians and philosophers converge in their wonder of the animal that has no use for the human being, be it a cow in the pasture or the cat that awaits us affectionately at the end of a day, but is a wonder in itself, a fragment of that Creation that for a long time seemed to have placed only the human being and their interests at the center of the world

“This happened because of the influence in Christian theology of philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, for whom animals were of clearly inferior rank, because they were seen as a-logoi beings, that is, not endowed with reason and intelligence and therefore not even with an immortal soul”, reflects Father Lintner. The same resurrection of Christ, however, if considered in the cosmological dimension, includes the salvation of animals. “John wrote that the Word became flesh and the term flesh includes the concept of fragility and vulnerability of the human being who is a creature, molded from the dust of the earth. Therefore, the term flesh expresses the vulnerability of the creature, which includes animals”, adds the South Tyrolean theologian, when explaining how it is possible to overcome one of the great questions of medieval scholastic theology, according to which salvation had to exclude animals because they are not endowed with an intellectual soul.

This cultural awareness, namely the exclusion of non-human beings from the plan of salvation, has often guided the hand of men and women, even non-believers, to mistreat animals and the planet. Yet this dichotomy is being overcome. As Pope Francis remarked in one of his catecheses, “One day we will see our animals again in the eternity of Christ”. Paolo De Benedetti, an animal theologian who recently passed away, went further when he wrote “in the eyes of a dying dog, it is possible to meet Jesus”. “If we believe that God created every living thing out of love and that he also made a covenant with animals after the flood, then it is obvious to believe that God does not simply resign himself to the suffering and death of an animal. There are approaches to extend the option for the poor to animals as well”. Lintner again recalls Laudato si’, where Pope Francis says, “this is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor; she ‘groans in travail’ (Rom 8:22). “In this sense, we encounter Christ in every suffering creature and in the eyes of a dying dog”, Lintner further explains, convinced that the Church still needs to reflect more deeply on the concept of the use and especially the killing of animals. This is possible today for the Catechism if there is a justification such as finding food or pharmaceutical experimentation that, while always keeping the Bible open, seems little in keeping with the words of the prophet Hosea, “And I will make for you[e] a covenant on that day with the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, and the creeping things of the ground; and I will abolish the bow, the sword, and war from the land; and I will make you lie down in safety” (Hos 2:20).

by Laura Eduati

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti